Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

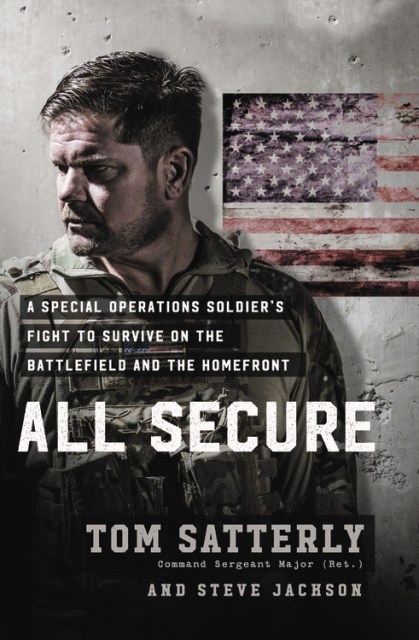

All Secure

A Special Operations Soldier's Fight to Survive on the Battlefield and the Homefront

Contributors

By Tom Satterly

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546076575

Price

$30.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

One of the most highly regarded special operations soldiers in American military history shares his war stories and personal battle with PTSD.

As a senior non-commissioned officer of the most elite and secretive special operations unit in the U.S. military, Command Sergeant Major Tom Satterly fought some of this country’s most fearsome enemies. Over the course of twenty years and thousands of missions, he’s fought desperately for his life, rescued hostages, killed and captured terrorist leaders, and seen his friends maimed and killed around him.

All Secure is in part Tom’s journey into a world so dark and dangerous that most Americans can’t contemplate its existence. It recounts what it is like to be on the front lines with one of America’s most highly trained warriors. As action-packed as any fiction thriller, All Secure is an insider’s view of “The Unit.”

Tom is a legend even among other Tier One special operators. Yet the enemy that cost him three marriages, and ruined his health physically and psychologically, existed in his brain. It nearly led him to kill himself in 2014; but for the lifeline thrown to him by an extraordinary woman it might have ended there. Instead, they took on Satterly’s most important mission-saving the lives of his brothers and sisters in arms who are killing themselves at a rate of more than twenty a day.

Told through Satterly’s firsthand experiences, it also weaves in the reasons-the bloodshed, the deaths, the intense moments of sheer terror, the survivor’s guilt, depression, and substance abuse-for his career-long battle against the most insidious enemy of all: Post Traumatic Stress. With the help of his wife, he learned that by admitting his weaknesses and faults he sets an example for other combat veterans struggling to come home.