Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

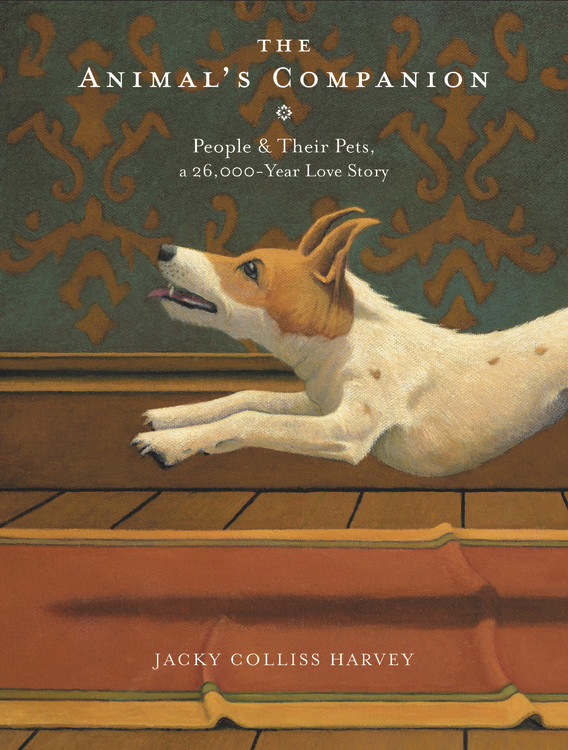

The Animal's Companion

People & Their Pets, a 26,000-Year Love Story

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.99Price

$36.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.99 $36.49 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A unique and compelling exploration of why humans need animal companions — from dogs and cats to horses, birds, and reptiles — through the eyes of a New York Times bestselling historical detective author.

In The Animal’s Companion, the acclaimed social anthropologist and author of Red: A History of the Redhead turns her keen eye for cultural investigation toward uncovering why humans have such a strong desire to share everyday life with pets. It’s a history that can be traced back to a cave in France where anthropologists discovered evidence of a boy and his dog taking a walk together — 26,000 years ago.

From those preserved foot and paw prints, Jacky Colliss Harvey draws on literary, artistic, and archaeological evidence to sweep readers through centuries and across continents to examine how our relationships with our pets have developed, but also stayed very much the same. Through delightful stories of the most famous, endearing, and sometimes eccentric pet owners throughout history, Colliss Harvey examines the when, the how, and the why of our connection to the animals we take into our lives, and suggests fascinating new insights into one of the most long-standing of all human love affairs.

In The Animal’s Companion, the acclaimed social anthropologist and author of Red: A History of the Redhead turns her keen eye for cultural investigation toward uncovering why humans have such a strong desire to share everyday life with pets. It’s a history that can be traced back to a cave in France where anthropologists discovered evidence of a boy and his dog taking a walk together — 26,000 years ago.

From those preserved foot and paw prints, Jacky Colliss Harvey draws on literary, artistic, and archaeological evidence to sweep readers through centuries and across continents to examine how our relationships with our pets have developed, but also stayed very much the same. Through delightful stories of the most famous, endearing, and sometimes eccentric pet owners throughout history, Colliss Harvey examines the when, the how, and the why of our connection to the animals we take into our lives, and suggests fascinating new insights into one of the most long-standing of all human love affairs.

Genre:

-

"...an engaging, insightful consideration of how anthropomorphism, cruelty, egocentrism, empathy, realism and sentimentality have blended and blurred across centuries -- teaching us a vast amount about animals, and even more about ourselves."The Irish Times

-

"When you read a book by Jacky Colliss Harvey, you learn a lot. And with the way she writes, deeply researched and with wit and erudition, you also have fun as you learn.Veteranscribe's

-

"[Jacky Colliss Harvey] writes, with affection and wit, of man and beast's enduring relationship, focusing on all aspects of our bond - from choosing to losing - and has great stories about notable people and their animal companions."Toronto Star

-

[A]...lively exploration of people and their pets... Numerous colourful animal tales enliven Colliss Harvey's latest book, but her real subject is their human companions, whom she considers through a lens of history, literature and art, as well as smatterings of science and psychology, all interwoven with diverting personal reminiscences... Colliss Harvey has an eye for surprising details and a lovely way with a description."The Sunday Times

-

"[Jacky Colliss Harvey]'s beautifully illustrated book is organized thematically and is perhaps best thought of as a series of essays on the various themes that the relationship between kept animals and humans throw up, such as choosing, naming, communication, and losing. However, for all its research into deeper matters, the real pleasure of The Animal's Companion lies in its stories. And they come thick and fast."The Spectator

-

"A well-researched, deeply crafted, wry and witty compendium on the importance of pets in our lives.... Our species' fondness for pets seems to be the one clear distinction we can claim as our own -- indeed, a case can be made for pets making us human. We urge you to read (or listen to) The Animal's Companion. You will come away as enthralled and entertained as we were."Bark.com

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316466219

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use