By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

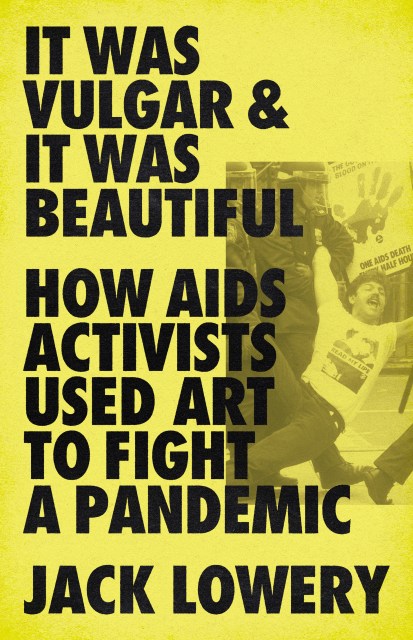

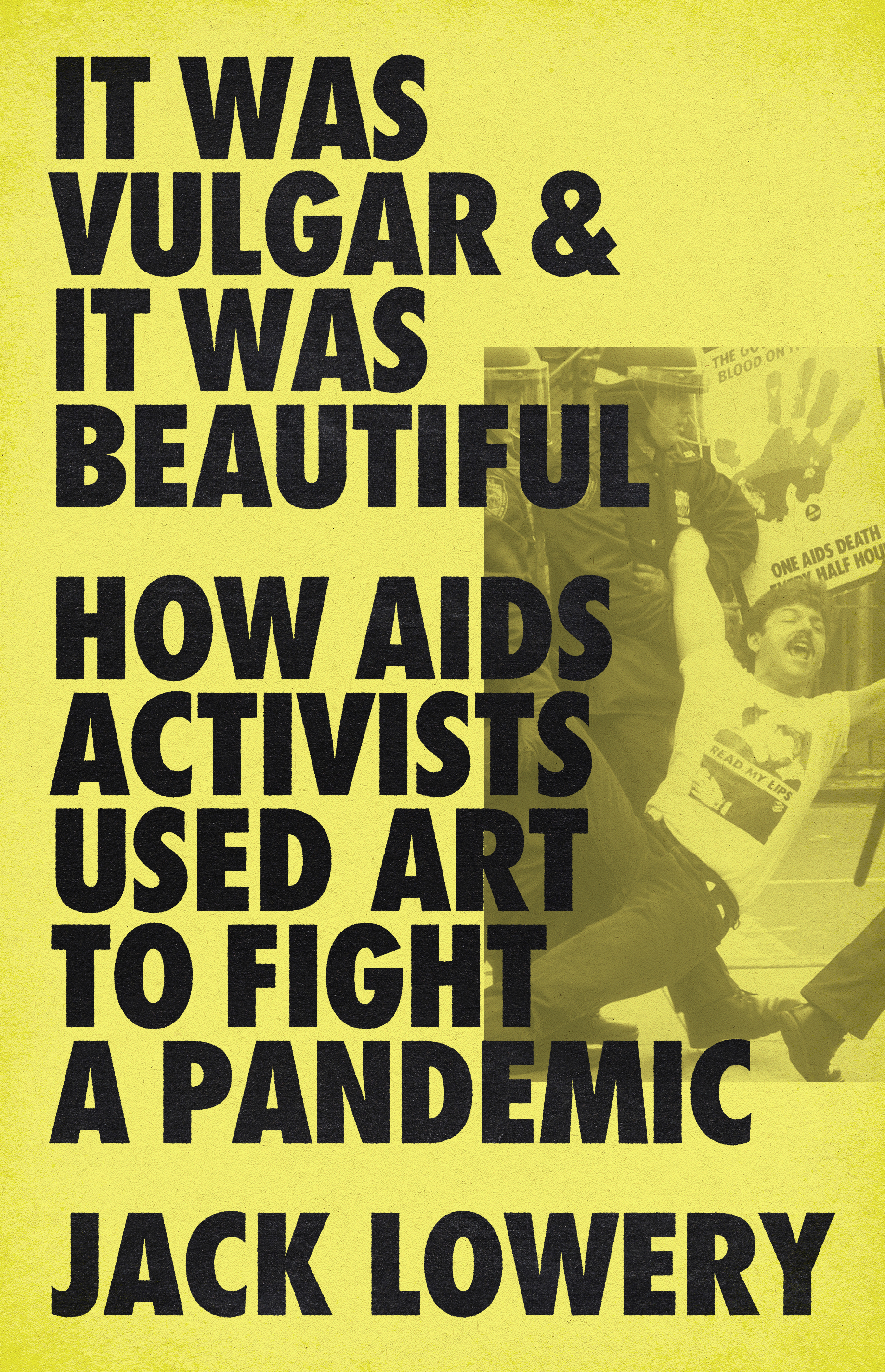

It Was Vulgar and It Was Beautiful

How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic

Contributors

By Jack Lowery

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781645036586

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $23.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the late 1980s, the AIDS pandemic was annihilating queer people, intravenous drug users, and communities of color in America, and disinformation about the disease ran rampant. Out of the activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), an art collective that called itself Gran Fury formed to campaign against corporate greed, government inaction, stigma, and public indifference to the epidemic.

Writer Jack Lowery examines Gran Fury’s art and activism from iconic images like the “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” poster to the act of dropping piles of fake bills onto the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Lowery offers a complex, moving portrait of a collective and its members, who built essential solidarities with each other and whose lives evidenced the profound trauma of enduring the AIDS crisis.

Genre:

-

“Lowery painstakingly reconstructs conversations and negotiations that compel a reader to feel the era’s anguish and urgency… An important contribution to the annals of AIDS, and, in hewing close to but fanning out from a narrow cast of characters, a sturdy template for chroniclers of complex sociopolitical movements.”Alexandra Jacobs, New York Times

-

“An unsparing account… Lowery tenderly reconstructs the tedious planning, overwhelming sadness and occasional joys of the era to create an accessible history of the AIDS crisis and the activists who fought to make a difference.”NPR

-

“[A] thoughtful, cogent new history.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Jack Lowery's compelling exploration of [Gran Fury] and their work is more timely now than ever, when activism is a necessary and vital part of our lives….Educational and entertaining, this look at queer history has a lot to tell us about what's going on today.”Buzzfeed

-

“Lowery debuts with a fascinating study of how art galvanized AIDS activism in the 1980s and ’90s…[He] provides crucial context about the history of the AIDS epidemic and draws vivid sketches of key players in Gran Fury. The result is a captivating look at the power of art as a political tool.”Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

“Lowery lovingly portrays the strength, effort, happy victories, and overwhelming sadness of [ACT UP’s] historic efforts… Art had a major role in the movement, and as this testimonial lays out, the people behind the art stand as pillars of beautiful humanity. This is a rich and necessary documentation.”Booklist (starred review)

-

“Lowery’s raw emotion strikes deep into the reader’s conscience. The context of how the art was incubated makes this narrative essential to the history of the AIDS epidemic…Recommended for all interested in how art can change the world.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

“A lively depiction of how graphic art can bring political activism to life.”Kirkus

-

“I picked up Jack Lowery’s It Was Vulgar and It Was Beautiful and didn’t stop reading it for the next three days. Lowery’s plainspoken, patient, and probing approach to his dramatic subject matter is totally compelling, and his focus on Gran Fury fills in a critical piece of aesthetic and political history. Anyone and everyone interested in still-urgent questions about the relations between art, activism, living, and dying should immediately read this book.”Maggie Nelson, author of The Argonauts

-

“As much as the book is about how art fits into activism, it’s also about how friendships and love affairs fit into a time of fear, grief, illness, and death amid a very closely knit social circle. It’s a fun, fascinating read that’s also a moving and personal one.”TheBody

-

“Lowery’s incisive book functions as a catalogue raisonné of the collective’s oeuvre over the eight years of its existence… It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful makes a compelling case for the significance of Gran Fury’s imagery to the efficacy of ACT UP.”The Gay & Lesbian Review

-

“Repackaging the collective’s travails for a mass-market audience, Lowery deftly untangles the lives and contributions of Gran Fury’s eleven core members while cementing the group’s importance within the larger saga of ACT UP.”Artforum

-

“Lowery cinematically captures the artists… This is a book for its subjects, a gift toward their legacy.”The Baffler

-

“Lowery writes with passion and purpose in his essential new non-fiction bookOutWord Magazine

-

“Jack Lowery has written an eminently readable and ultimately inspiring story about the intersection of politics and art.”Powell’s Books Blog

-

“This riveting new perspective on AIDS activism is an emotional portrait of anger, grief, loss and love—and a testament to art’s power to transform.”Spectrum Culture

-

“Jack Lowery has written an engaging, provocative, and moving book about one of the most successful political movements in American history, a painstakingly researched narrative about how activism and art saved untold lives. At a time when the lessons of Gran Fury and ACT UP are more crucial than ever, this is essential reading.”Alex Halberstadt, author of Young Heroes of the Soviet Union

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use