By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

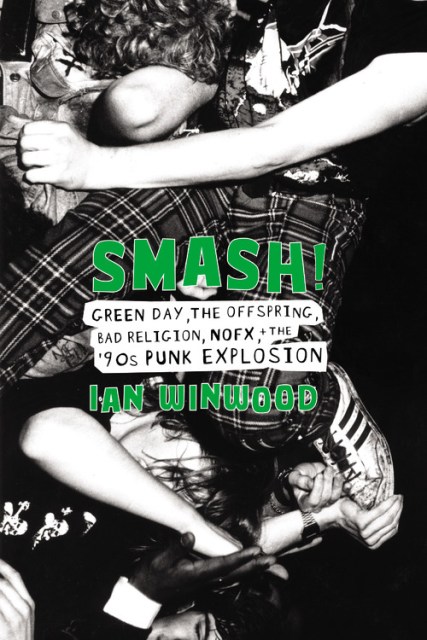

Smash!

Green Day, The Offspring, Bad Religion, NOFX, and the '90s Punk Explosion

Contributors

By Ian Winwood

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306902741

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Two decades after the Sex Pistols and the Ramones birthed punk music into the world, their artistic heirs burst onto the scene and changed the genre forever. While the punk originators remained underground favorites and were slow burns commercially, their heirs shattered commercial expectations for the genre. In 1994, Green Day and The Offspring each released their third albums, and the results were astounding. Green Day’s Dookie went on to sell more than 15 million copies and The Offspring’s Smash remains the all-time bestselling album released on an independent label. The times had changed, and so had the music.

While many books, articles, and documentaries focus on the rise of punk in the ’70s, few spend any substantial time on its resurgence in the ’90s. Smash! is the first to do so, detailing the circumstances surrounding the shift in ’90s music culture away from grunge and legitimizing what many first-generation punks regard as post-punk, new wave, and generally anything but true punk music.

With astounding access to all the key players of the time, including members of Green Day, The Offspring, NOFX, Rancid, Bad Religion, Social Distortion, and many others, renowned music writer Ian Winwood at last gives this significant, substantive, and compelling story its due. Punk rock bands were never truly successful or indeed truly famous, and that was that — until it wasn’t. Smash! is the story of how the underdogs finally won and forever altered the landscape of mainstream music.

Genre:

-

"An energetic history of the punk revolution of the 1990s, inspired by bands such as the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, and X...[Winwood has a] deep knowledge and thick dossier of interviews with these three-chord revolutionaries...This is a ripping fun music history and strongly reasoned argument for the place of oft-derided 1990s Cali punk in the annals of pop music."Publishers Weekly

-

"[A] straightforward account of the improbably profitable second coming of punk rock...[Winwood] writes with authoritative enthusiasm about the 1990s rise of bands like Green Day and the Offspring and their broader relationship to the always-contentious question, 'what is punk?'...His knowing humor will appeal to younger fans and those who were there. A savvy reminiscence of the era when punk finally paid its debt to society."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Through a series of interviews, Winwood documents the 1990s, the decade in which punk rock emerged from basements in California to the Billboard charts...The author thoughtfully maps the transformation of the punk rock ethos for both the record labels and the bands as they experienced an unprecedented wave of commercial success...Fans of punk and music in general will enjoy this work."Library Journal

-

"A phenomenal piece of work."-LA Weekly

-

"The amount of research and fact checking that the author undertook...is staggering. And it doesn't hurt that Winwood is a bloody great writer whose natural wit and sharp, incisive style turns what could have, at times, become a dry and slightly repetitive read into a compulsive, interesting and intriguing page turner... The nineties was, as Dickens once said, the best of times and the worst of times, but it will always be the era when punk rock conquered the world and in doing so made things a little better and Ian Winwood perfectly captures the history of, and everything that made that moment in time special, with Smash!."Mass Movement

-

"Winwood goes into depth about all things punk, getting commentary straight from many of the musicians that helped punk go mainstream. Winwood did such a great job with this book."The Hype

-

"Smash! gives us first-hand accounts of how '90s skate punk came to be. And while some of the story is public knowledge, there's a ton of juicy stuff in there that we had no clue about."Kerrang!

-

"Winwood gives us a side of punk rock that's not often discussed...It's not a complete history of the punk era. Rather it's a history of those who made the biggest impact...A loving homage to a forgotten era of punk...It's not only a story about the bands, but it's also a story about how punk rock rose from the ashes to conquer once again."Genre Is Dead

-

"Smash! is a compelling narrative of what led up to the punk breakout...It gives unparalleled access to the key artists, letting their voices shine through...This is important not just for fans of those particular groups but also for anyone trying to understand how punk rock became viable as a mainstream, commercial genre of music."Oy Oy Oy Gevalt!

-

"If you have any interest in how punk came to be the beast that it is today, you should seek out Smash!. The '90s punk explosion is a remarkable, if often overlooked, part of musical history. Finally, it has the book its story deserves."Kerrang!

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use