Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

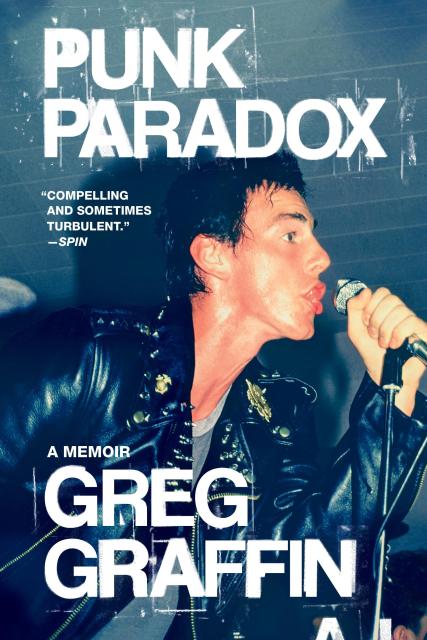

Punk Paradox

A Memoir

Contributors

By Greg Graffin

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2023

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306924590

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $65.00 $82.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the legendary singer-songwriter of Bad Religion comes a historical memoir and cultural criticism of punk rock’s evolution.

Greg Graffin is the lead vocalist and songwriter of Bad Religion, recently described as “America’s most significant punk band.” Since its inception in Los Angeles in 1980, Bad Religion has produced 18 studio albums, become a long-running global touring powerhouse, and has established a durable legacy as one of the most influential punk rock bands of all time.

Punk Paradox is Graffin’s life narrative before and during L.A. punk’s early years, detailing his observations on the genre’s explosive growth and his band’s steady rise in importance. The book begins by exploring Graffin’s Midwestern roots and his life-changing move to Southern California in the mid-’70s. Swept up into the burgeoning punk scene in the exhilarating and often-violent streets of Los Angeles, Graffin and his friends formed Bad Religion, built a fanbase, and became a touring institution. All these activities took place in parallel with Graffin’s never ceasing quest for intellectual enlightenment. Despite the demands of global tours, recording sessions, and dedication to songwriting, the author also balanced a budding academic career. In so doing, he managed to reconcile an improbable double-life as an iconic punk rock front man and University Lecturer in evolution.

Graffin’s unique experiences mirror the paradoxical elements that define the punk genre—the pop influence, the quest for society’s betterment, music’s unifying power—all of which are prime ingredients in its surprising endurance. Fittingly, this book argues against the traditional narrative of the popular perception of punk. As Bad Religion changed from year to year, the spirit of punk—and its sonic significance—lived on while Graffin was ever willing to challenge convention, debunk mythology, and liberate listeners from the chains of indoctrination.

As insightful as it is exciting, this thought-provoking memoir provides both a fly on the wall history of the punk scene and astute commentary on its endurance and evolution.

Genre:

-

LOUDER, "Best Music Books from 2022"

-

“Greg Graffin’s new memoir documents the endless trials and tribulations, as well as the colorful characters who come along with it, all taking place on the allegorical campus of Graffin U. Rather than focusing on elements like the now-iconic crossbuster logo or major moments in the band’s rich musical canon, PUNK PARADOX tells a compelling — and sometimes turbulent — tale of an artist and academic’s pursuit for understanding and (dare I say?) enlightenment.”SPIN

-

"There's much to commend in Graffin's thoughtful, thorough autobiography."LOUDER

-

“Fascinating… Written with the nuanced detail for research of an academic, but balanced out with a punk rocker’s experience, Punk Paradox is a rock memoir unlike most…Greg Graffin knows how to tell a compelling story.”New Noise

-

“A captivating character study of someone pursuing his passions in seemingly contradictory fields and staying true to himself and his own inner compass. Ultimately being able to experience that journey in detail as a reader may be Punk Paradox’s greatest gift.”Flood

-

"A well-crafted memoir and manifesto... An entertaining, memorable look at 'the most intractable paradox of all: punk as a positive force in society.'"Kirkus

-

"The hard-driven Graffin compellingly and eloquently describes the rewards and pitfalls of a career as successful musician and academic that will fascinate general readers."Library Journal

-

"[A] thoughtful, deeply personal memoir... [Greg Graffin’s] descriptions of the natural world in relation to his emotional growth is as compelling as it is astute, and Graffin is passionate in his reminiscences of a time when punk rock was not distorted with the often deserved stereotype of violence and anger. Readers will discover a trove of insights into the music industry and living creatively.”Booklist

-

“Greg Graffin has been in the guts of the Punk Rock machine for literally decades. I would dare say there's not a lot you can tell him he doesn't already know. Any observation Greg makes is from the front line and worthy of consumption. In Punk Paradox, Greg meticulously lays out the evolution of Bad Religion not only as a band working to stay relevant but also as an entity that's had to carefully navigate great success and the myriad challenges that come with it. Good stuff.”Henry Rollins

-

"Fearlessly pulling back the veil to show us the unpretentious, self-aware, deeply sensitive pacifist with a love for humanity and going against the grain, Greg Graffin shatters all expectations and assumptions of what it means to be punk rock, inviting us all to evolve."Aimee Allen, lead vocalist of The Interrupters

-

“Before Nirvana ever recorded a note, Greg Graffin’s band, Bad Religion, was brilliantly fusing punk rock intensity with philosophy. Who else but Graffin would cite both Black Flag’s ‘Nervous Breakdown’ and Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle as major influences?Danny Goldberg, author of Serving The Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain

With wit and brutal honesty, Graffin brings to life his unique journey: his parallel paths as an academic with a PhD in Zoology and that of an internationally influential punk rocker. He offers insights into band dynamics, the creative process, the way that art and career intersect with personal lives, the Southern California punk scene of the ’80s and ’90s and the currents of the music business that artists deal with along the way.”