Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

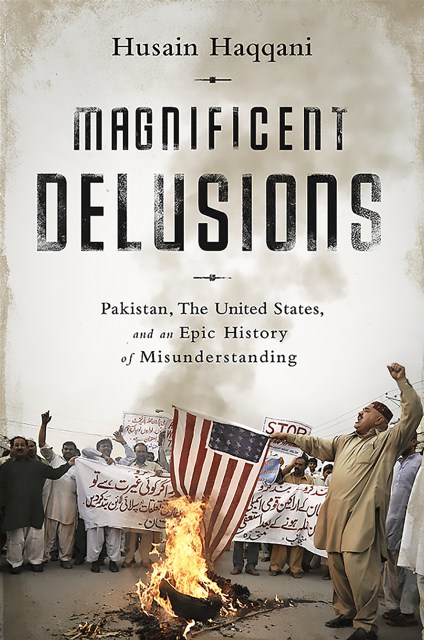

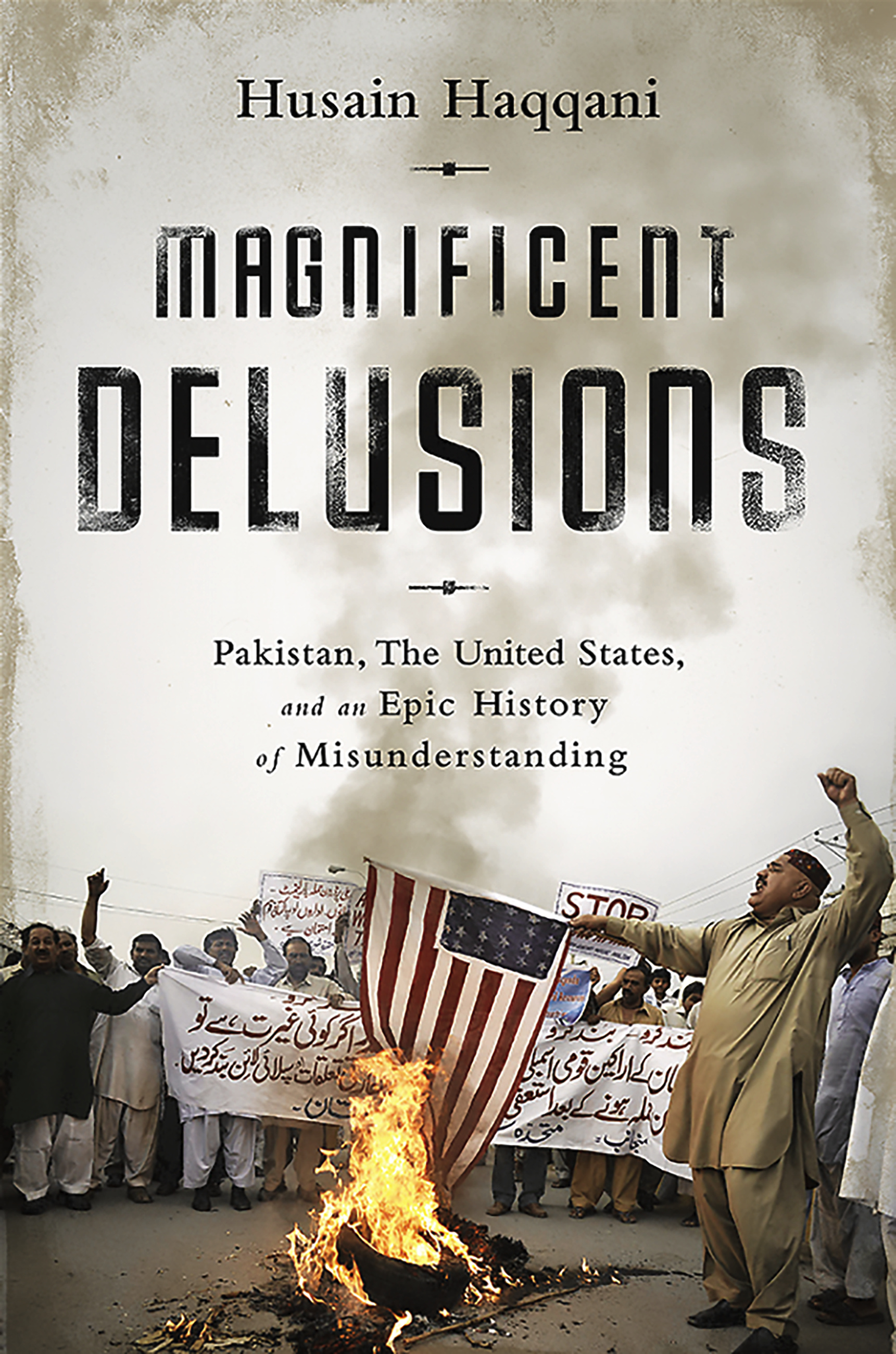

Magnificent Delusions

Pakistan, the United States, and an Epic History of Misunderstanding

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 3, 2015

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610394734

Price

$24.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 3, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The countries are not merely at odds. Each believes it can play the other — with sometimes absurd, sometimes tragic, results. The conventional narrative about the war in Afghanistan, for instance, has revolved around the Soviet invasion in 1979. But President Jimmy Carter signed the first authorization to help the Pakistani-backed mujahedeen covertly on July 3 — almost six months before the Soviets invaded. Americans were told, and like to believe, that what followed was Charlie Wilson’s war of Afghani liberation, with which they remain embroiled to this day. It was not. It was General Zia-ul-Haq’s vicious regional power play.

Husain Haqqani has a unique insight into Pakistan, his homeland, and America, where he was ambassador and is now a professor at Boston University. His life has mapped the relationship of the two countries and he has found himself often close to the heart of it, sometimes in very confrontational circumstances, and this has allowed him to write the story of a misbegotten diplomatic love affair, here memorably laid bare.

-

Library Journal

“Haqqani uses his wealth of personal experience to present a detailed account of the genesis and evolution of U.S.-Pakistani relations over the last 60 years… The book is a useful resource for academics, journalists, and policymakers at all levels.”

Publishers Weekly

“Insightful if disturbing... Making it clear why he is persona non grata in his homeland, Haqqani concludes that military aid has undermined Pakistan's democracy, converting it into a rentier state living off American money rather than its people's productivity.”

Asian Age

“The book is part memoir, part searing indictment of Pakistan's flawed strategy of using jihadis to secure its strategic space… [Haqqani proves] himself to be a diligent and tireless researcher who backs up almost every stinging commentary on Pakistan's journey since independence to the present day, with fact.” -

Mark Moyer, Wall Street Journal

“[Haqqani's] purpose isn't to narrate his service as ambassador or score political points but to outline the contours of American relations with Pakistan over time, with a final chapter depicting the 2011 collapse as a new instance of historical trends. While one might desire a fuller accounting of his ambassadorship, the book covers its chosen ground superbly.”

Richard Leiby, Washington Post

“A solid synthesis of history, political analysis and social critique."

Lisa Curtis, National Interest

“If you want a better understanding of why U.S. policy has failed so miserably in Pakistan, you should read Husain Haqqani's latest book… Fast-paced and highly readable… Haqqani has provided a well-documented and interesting account of the policy disconnects between the United States and Pakistan. His book should make a tremendous contribution toward grounding U.S. policy toward Pakistan in more realistic assumptions that will help avoid future crises between the two countries.”

Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“[An] insightful, painful history of Pakistani-American relations… Demonstrating no mercy to either party, Haqqani admits that Pakistan verges on failed-state status but shows little patience with America's persistently shortsighted, fruitless policies.”