By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

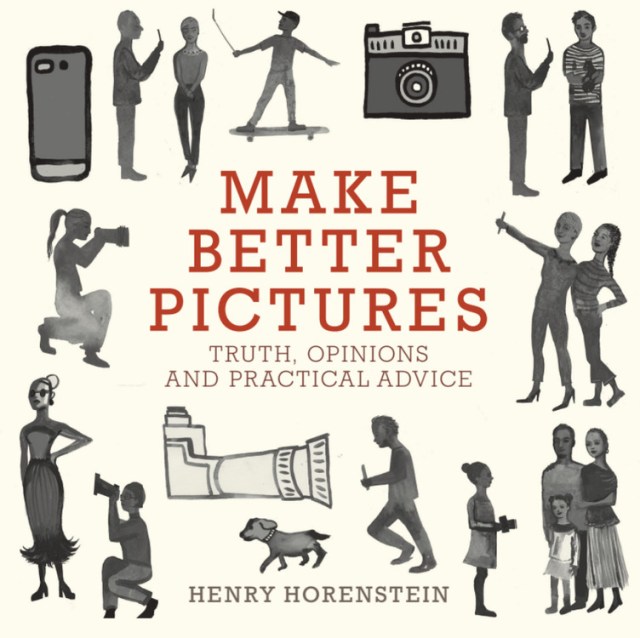

Make Better Pictures

Truth, Opinions, and Practical Advice

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316230889

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Henry Horenstein may be the world’s bestselling photography teacher, with more than 700,000 copies of his photography manuals sold. Now, in this easily digestible book of wisdom, he distills a career’s worth of instruction into one hundred memorable pieces of advice.

Photography has never been a bigger part of our lives. But how do you transform everyday snapshots into enduring images — or merely upgrade your Instagram game? With images illustrating the impact of each tip, and with examples drawn from iconic artists, Horenstein shows casual and expert photographers alike how to take the best photographs on every device — from a DSLR to an iPhone.

Photography has never been a bigger part of our lives. But how do you transform everyday snapshots into enduring images — or merely upgrade your Instagram game? With images illustrating the impact of each tip, and with examples drawn from iconic artists, Horenstein shows casual and expert photographers alike how to take the best photographs on every device — from a DSLR to an iPhone.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use