Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

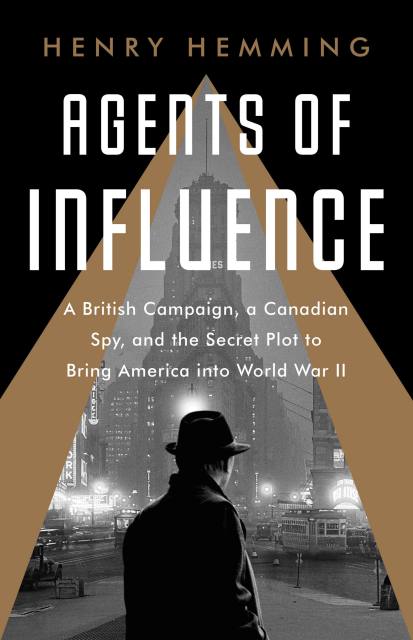

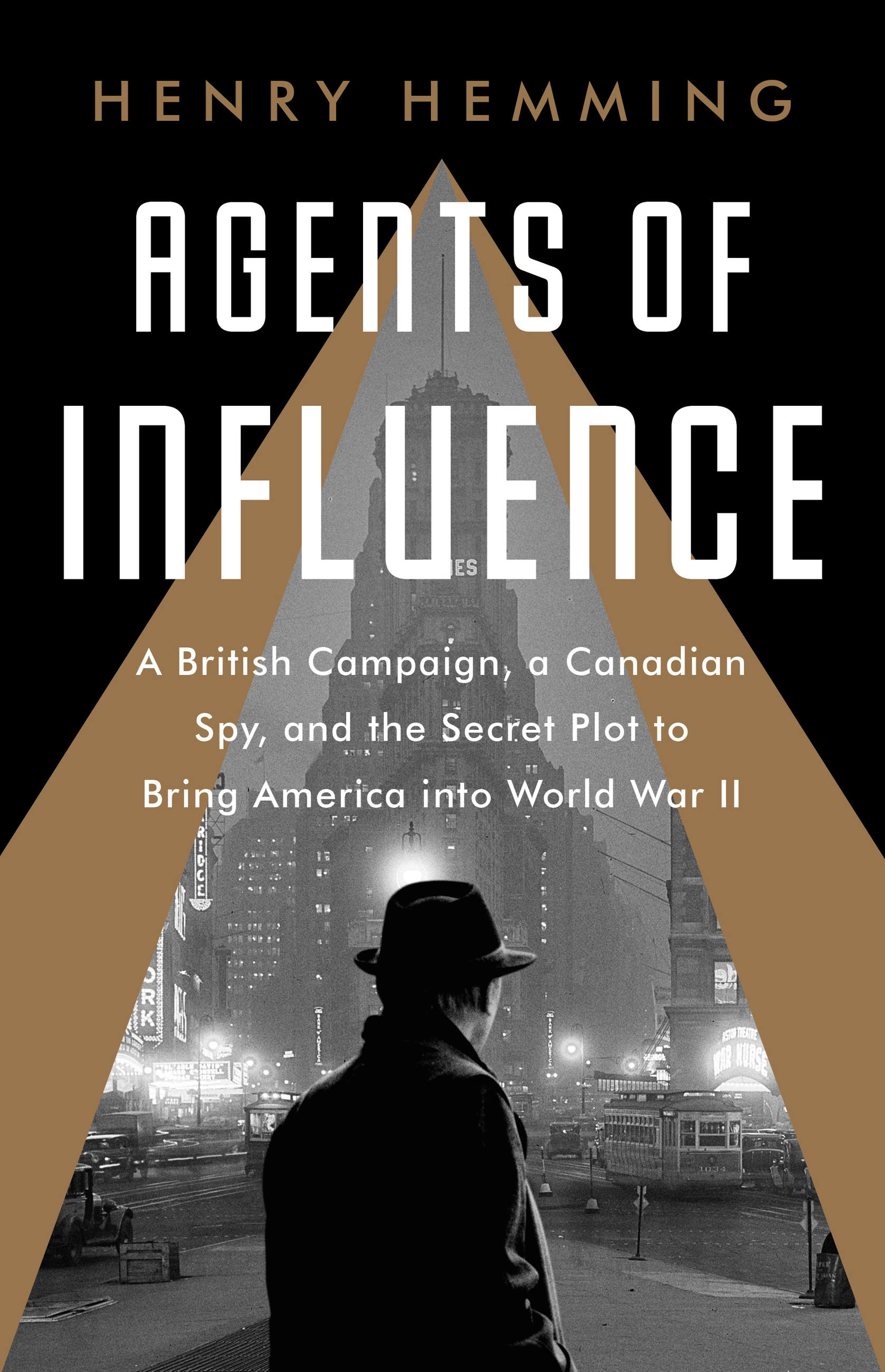

Agents of Influence

A British Campaign, a Canadian Spy, and the Secret Plot to Bring America into World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742116

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The astonishing story of the British spies who set out to draw America into World War II

As World War II raged into its second year, Britain sought a powerful ally to join its cause-but the American public was sharply divided on the subject. Canadian-born MI6 officer William Stephenson, with his knowledge and influence in North America, was chosen to change their minds by any means necessary.

In this extraordinary tale of foreign influence on American shores, Henry Hemming shows how Stephenson came to New York–hiring Canadian staffers to keep his operations secret–and flooded the American market with propaganda supporting Franklin Roosevelt and decrying Nazism. His chief opponent was Charles Lindbergh, an insurgent populist who campaigned under the slogan “America First” and had no interest in the war. This set up a shadow duel between Lindbergh and Stephenson, each trying to turn public opinion his way, with the lives of millions potentially on the line.