By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

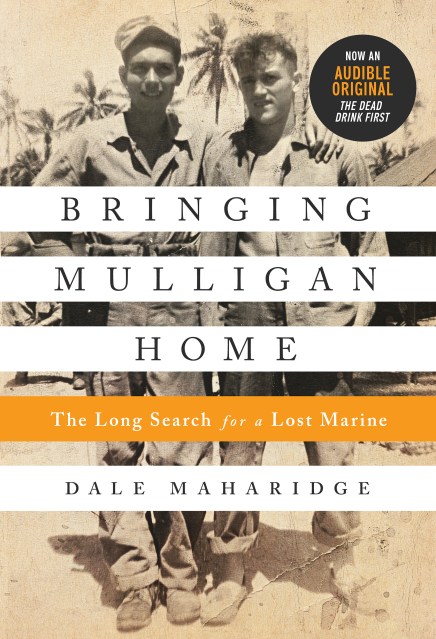

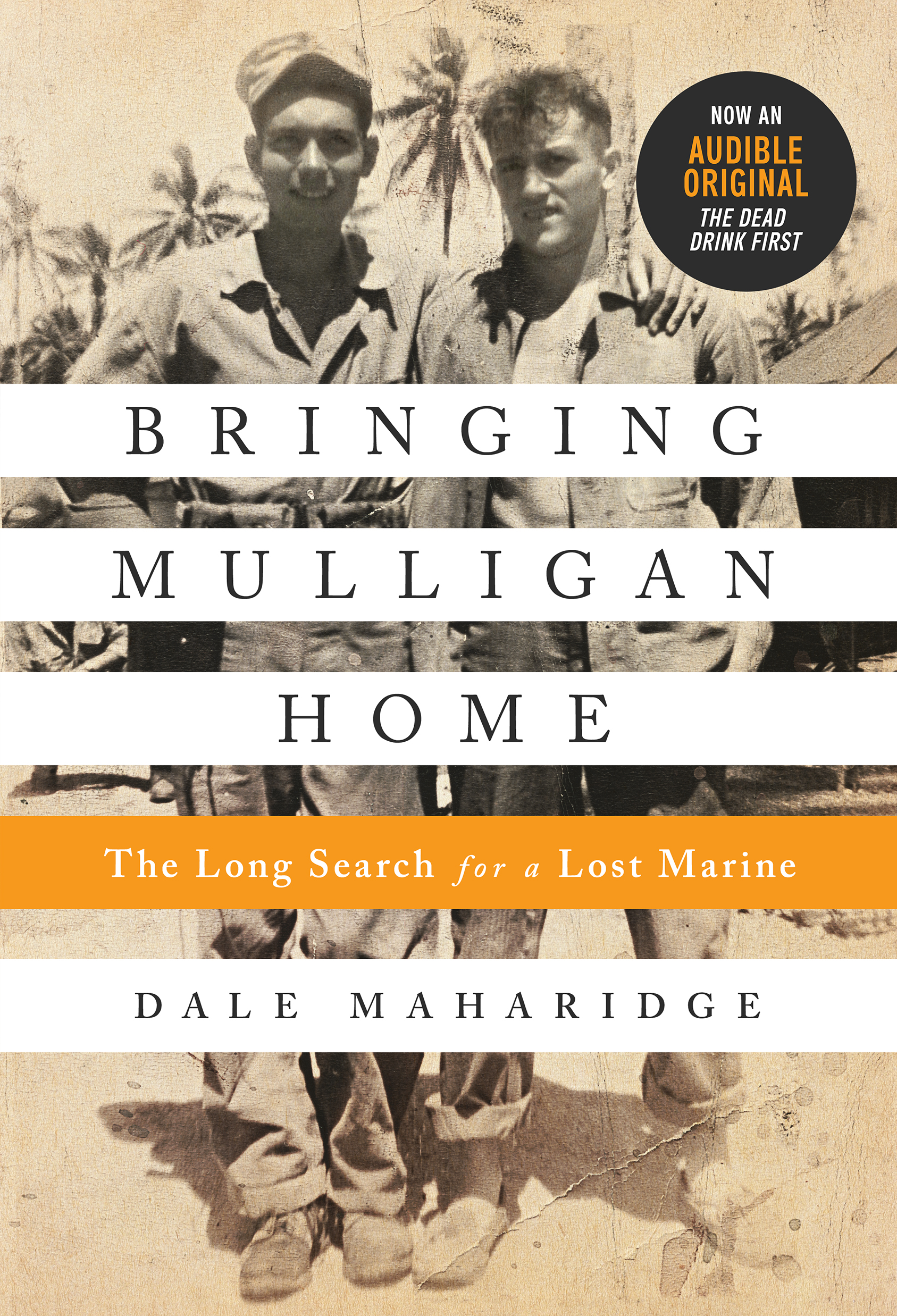

Bringing Mulligan Home

The Long Search for a Lost Marine

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 21, 2019

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742765

Price

$17.99Price

$23.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 21, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Now an Audible Original “THE DEAD DRINK FIRST” Sergeant Steve Maharidge returned from World War II an angry man. For a long time, the only evidence that remained of his service in the Marines was a photograph of himself and a buddy that he tacked to the basement wall. When his son, Dale Maharidge, set out to discover what happened to the friend in the photograph, he found that wars do not end when the guns go quiet. The scars and demons remain for decades. Bringing Mulligan Home is the book on which the hit Amazon Audible Original, The Dead Drink First, is based. Years after the initial publication of the book, Dale Maharidge and an ad-hoc team of committed researchers kept working to bring closure for Sgt. Maharidge, his family, and his mysterious friend. For fans of The Dead Drink First, this newly updated edition enriches and deepens the experience of the Audible Original, and provides—for the first time in print—a resolution to Maharidge’s story of fathers and sons, war and the long oft-forgotten postwar for America’s Greatest Generation.

-

"Gripping and unforgettable-a son's search for his father in the shattered ruins of the Pacific War"Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes

-

"Through deep and sensitive interviewing, Dale Maharidge has achieved what many have previously thought impossible: he has opened up the "silent generation" of World War Two veterans and enabled them to tell their stories. These veterans, US marines and Japanese who met as enemies in the Pacific, are no mythologized heroes or villains, but flesh-and-blood humans describing the true horror that has always been, and always will be, war. Maharidge enables these survivors to speak of the war with such honesty that they strip away all its glamour, break your heart and win it all at once. Part memoir, part vivid history, part a searing examination of war trauma, Bringing Mulligan Home gives us an entirely fresh look at "The Good War" that may well change our view of it forever."Helen Benedict, author of The Lonely Soldier: The Private War of Women Serving in Iraq and Sand Queen

-

"A moving memoir. . .A powerful narrative of the dark side of American combat in the Pacific theater and the persistence of resulting injuries decades after the war ended."Kirkus

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use