Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

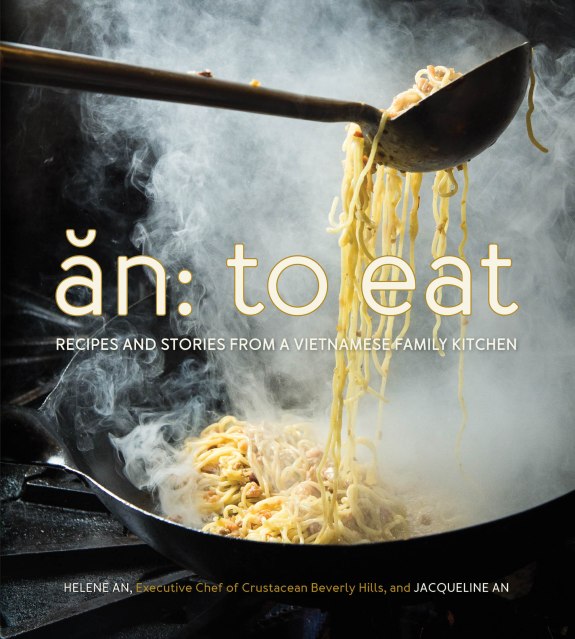

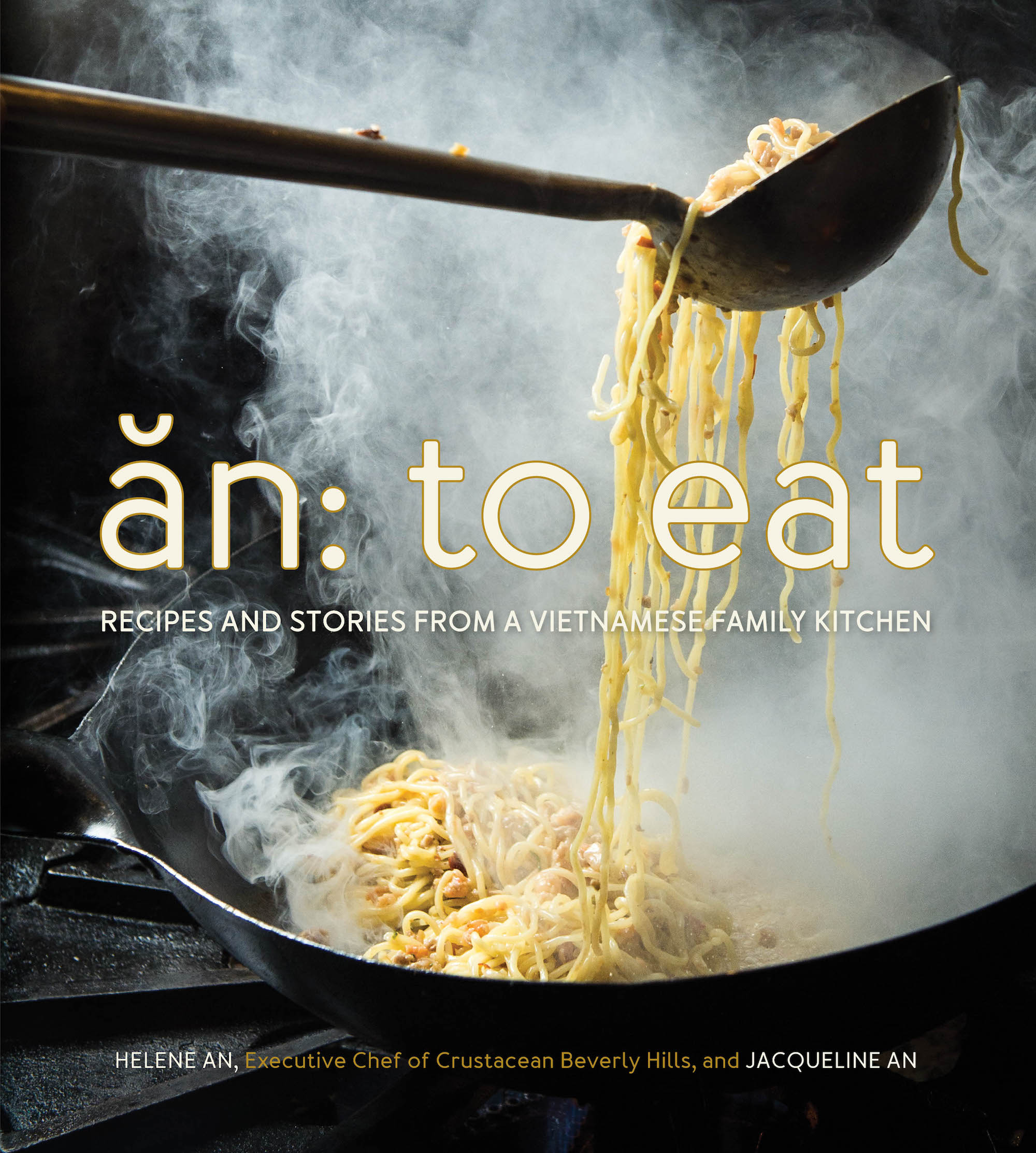

An: To Eat

Recipes and Stories from a Vietnamese Family Kitchen

Contributors

By Helene An

By Jacqueline An

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.99Price

$26.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $20.99 $26.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Helene’s transformation from pampered “princess” in French Colonial Vietnam, to refugee then restaurateur, and her journey from Indochina’s lush fields to family kitchen gardens in California are beautifully chronicled throughout the book. The result is a fascinating peek at a lost world, and the evolution of an extraordinary cuisine. The 100 recipes in An: To Eat feature clean flavors, simple techniques, and unique twists that could only have come from Helene’s personal story.

Genre:

-

“An: To Eat isn't just a good cookbook, it's a hell of a story.”

—Epicurious.com

“An: To Eat is a beautifully photographed (by Evan Sung) book that combines many of Crustacean's recipes with the central story of the An family.”

—Los Angeles Times

"It's so wonderful: The An story, the An family, and especially the An food. Vietnamese royal cuisine meets L.A. flair."

—Alan Richman, 16-time James Beard Foundation winner for food writing and GQ food correspondent

Chef Helene An's talent for composing flavors is virtuosic. Her contribution to the California culinary landscape places her firmly in the ranks of Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck. An: To Eat grants us a peek at some of her delectably covert recipes--after all, everyone loves a tasty secret."

—Eddie Lin, Los Angeles Times food writer

"Chef An's cooking isn't simply about food. It's a celebration of life, of family, of survival and triumph. Her life is a tribute to living well — and living with love!"

—Merrill Shindler, KABC Radio

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762458363

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use