By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

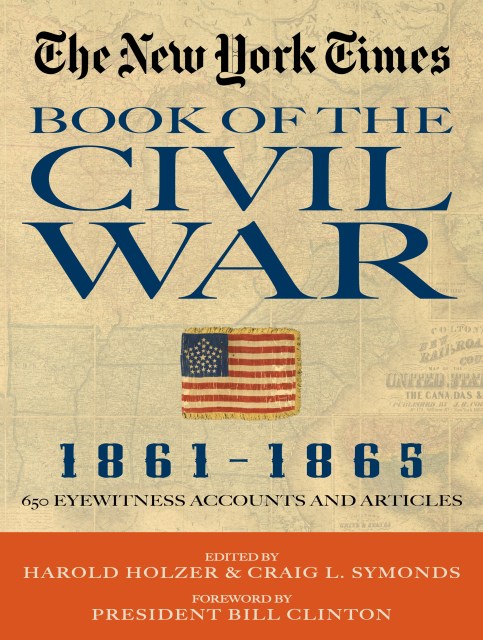

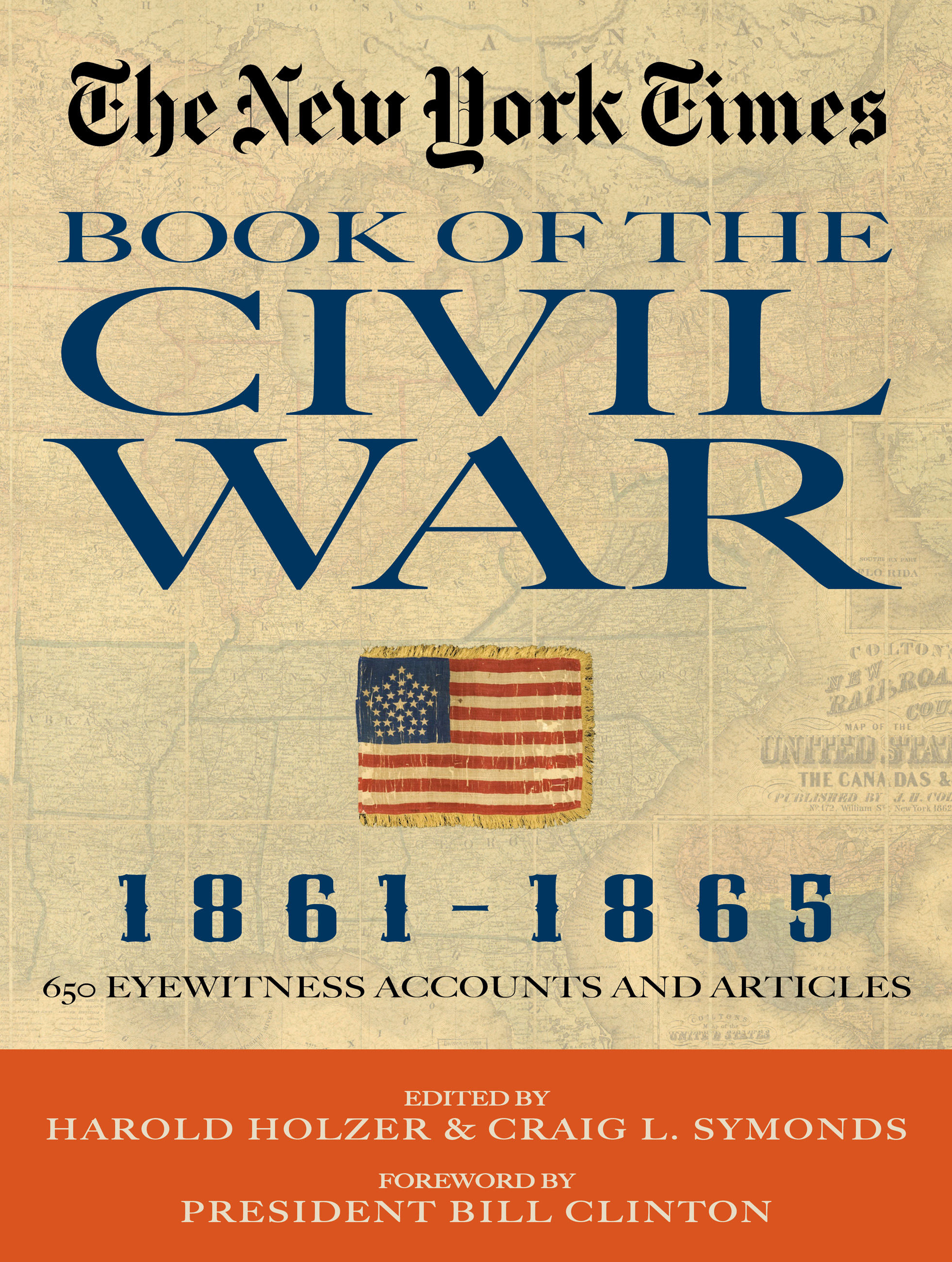

New York Times Book of the Civil War 1861-1865

650 Eyewitness Accounts and Articles

Contributors

Edited by Harold Holzer

Edited by Craig Symonds

Foreword by President Bill Clinton

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2010

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603763769

Price

$23.99Price

$30.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $23.99 $30.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The New York Times, established in 1851, was one of the few newspapers with correspondents on the front lines throughout the Civil War. The Complete Civil War collects every article written about the war from 1861 to 1865, plus select pieces before and after the war and is filled with the action, politics, and personal stories of this monumental event. From the first shot fired at Fort Sumter to the surrender at Appomattox, and from the Battle of Antietam to the Battle of Atlanta, as well as articles on slavery, states rights, the role of women, and profiles of noted heroes such as Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, the era comes alive through these daily first-hand accounts.

More than 600 of the most crucial and interesting articles in the book? Typeset and designed for easy reading

Commentary by Editors and Civil War scholars Harold Holzer and Craig Symonds

More than 104,000 additional articles on the DVD-ROM? every article the Times published during the war.

A detailed chronology highlights articles and events of interest that can be found on the disk.

Strikingly designed and illustrated with hundreds of maps, historical photographs, and engravings, this book is a treasure for Civil War and history buffs everywhere.

“This is a fascinating and riveting look at the most important event in American history as seen through the eyes of an institution that was emerging as the most important newspaper in American history. Â In these pages, the Civil War seems new and fresh, unfolding day after anxious day, as the fate of the republic hangs in the balance.” –Â Ken Burns

“Serious historians and casual readers alike will find this extraordinary collection of 600 articles and editorials about the Civil War published in The New York Times before and during the war of great value and interest . . . enough to keep the most assiduous student busy for the next four years of the war’s sesquicentennial observations.” –Â James McPherson

“This fascinating work catapults readers back in time, allowing us to live through the Civil War as daily readers of The New York Times, worrying about the outcome of battles, wondering about our generals, debating what to do about slavery, hearing the words that Lincoln spoke, feeling passionate about our politics. Symonds and Holzer have found an ingenious new way to experience the most dramatic event in our nation’s history.” — Doris Kearns Goodwin

“Harold Holzer and Craig Symonds have included not only every pertinent article from the pages of The Times, but enhanced and illuminated them with editorial commentary that adds context and perspective, making the articles more informative and useful here than they were in the original issues. Nowhere else can readers of today get such an understanding of how readers of 1861-1865 learned of and understood their war.” — William C Davis

The DVD runs on Windows 2000/XP or Mac OS X 10.3 or later.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use