Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

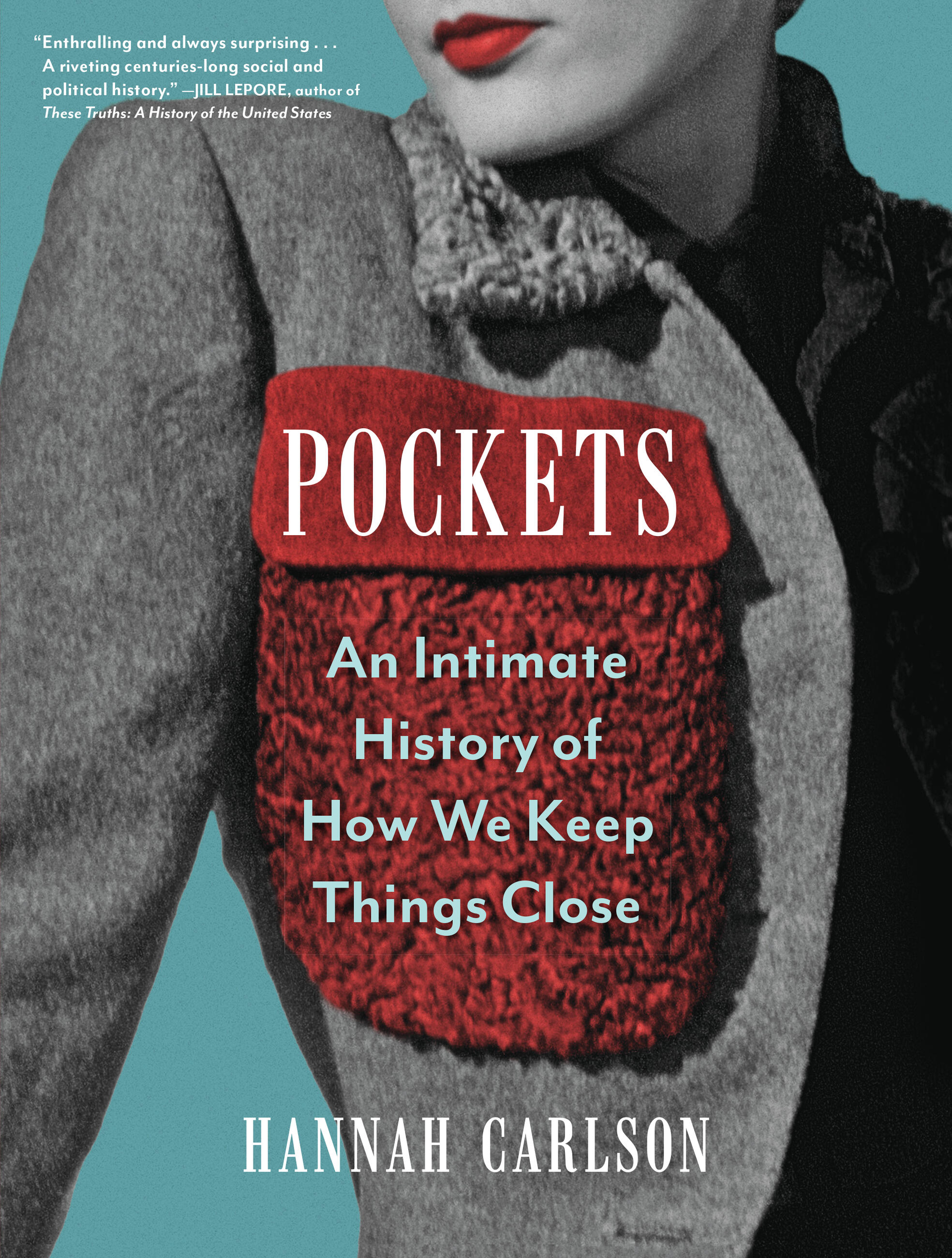

Pockets

An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 12, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Pockets "showcases the best features of cultural history: a lively combination of visual, literary and documentary evidence. As sumptuously illustrated as it is learned … this highly inventive and original book demands a pocket sequel.” ―Jane Kamensky, Wall Street Journal

Who gets pockets, and why?

It’s a subject that stirs up plenty of passion: Why do men’s clothes have so many pockets and women’s so few? And why are the pockets on women’s clothes often too small to fit phones, if they even open at all? In her captivating book, Hannah Carlson, a lecturer in dress history at the Rhode Island School of Design, reveals the issues of gender politics, security, sexuality, power, and privilege tucked inside our pockets.

Throughout the medieval era in Europe, the purse was an almost universal dress feature. But when tailors stitched the first pockets into men’s trousers five hundred years ago, it ignited controversy and introduced a range of social issues that we continue to wrestle with today, from concealed pistols to gender inequality. See: #GiveMePocketsOrGiveMeDeath.

Filled with incredible images, this microhistory of the humble pocket uncovers what pockets tell us about ourselves: How is it that putting your hands in your pockets can be seen as a sign of laziness, arrogance, confidence, or perversion? Walt Whitman’s author photograph, hand in pocket, for Leaves of Grass seemed like an affront to middle-class respectability. When W.E.B. Du Bois posed for a portrait, his pocketed hands signaled defiant coolness.

And what else might be hiding in the history of our pockets? (There’s a reason that the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets are the most popular exhibit at the Library of Congress.) Thinking about the future, Carlson asks whether we will still want pockets when our clothes contain “smart” textiles that incorporate our IDs and credit cards.

Pockets is for the legions of people obsessed with pockets and their absence, and for anyone interested in how our clothes influence the way we navigate the world.

Genre:

-

“Sweeping gracefully over half a millennium of Western culture... Carlson’s study showcases the best features of cultural history… As sumptuously illustrated as it is learned… this highly inventive and original book demands a pocket sequel.”Wall Street Journal

-

In her nifty “Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close,” Hannah Carlson unbuttons the politics behind who gets to hide their belongings, and where.New York Times Book Review

-

“Delightfully wide-ranging... Carlson’s winning book depicts the range and relevance of the pocket, which can be a metaphor for abundance or perversion, possession or secrecy—and a way of managing the efficiencies of life.”The New Yorker

-

"An entertaining, slightly academic look at how attitudes toward pockets have changed over the course of the past several centuries... juicy anecdotes."Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

“Who knew the humble pocket could hold so much history? In this enthralling and always surprising account, Hannah Carlson turns the pocket inside out and out tumble pocket watches, coins, pistols, and a riveting centuries-long social and political history.”Jill Lepore, author of These Truths: A History of the United States

-

“If you’re a man, you might wonder why someone would write an entire book about pockets…if you’re a woman, the story of Pockets pretty much illuminates all of human history. Either way, once you pick up Pockets, you’ll never forget its weird and wonderful lessons of power and possession.”Faith Salie, contributor to CBS News Sunday Morning and regular panelist on NPR’s Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!

-

“From feminine codes of secrecy to the fascinating culture of smart textiles, Carlson’s book is that rare thing: an exhaustive social history that’s also un-put-downable. Pockets reminds us that what we hold close says everything about who we are, what we value, and why it matters.”Jessica Helfand, Design Observer

-

“Rarely is such a feat of scholarship also such a delight. Carlson’s comprehensive history is among the best fashion books I’ve ever read. This deceptively simple premise contains surprising stories of the ways that politics, law, and technology manifest themselves in the clothes we wear. But the best part is that this book is full of so much assorted delightful useful miscellany—just like the pocket itself.”Avery Trufelman, host and creator of “Articles of Interest” podcast

-

“Fascinating. Drawing from literary and artistic sources; media commentary; behavioral studies; and object histories, Carlson offers an enlightening and engaging account of the sexual politics underlying the uneven use of pockets in the design of men’s and women’s dress.”—Andrew Bolton, the Wendy Yu Curator in Charge, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

“Pockets is absolutely fascinating and beautifully written.”Dr. Valerie Steele, director and chief curator, The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology

-

“Witty, wise, and totally mind-bending, this deeply researched, beautifully written book not only recovers the hidden history of pockets, but also reveals the ways those familiar but often ignored pouches reflected (and sometimes reshaped) cultural understandings of objects and the persons that carry them.”Bruce J. Schulman, William E. Huntington Professor of History, Boston University, and author of Making the American Century

-

“Carlson’s fascinating book—a historical who, what, where, why and when with the pocket as its central character—is as delightfully gripping as a spy novel.”Linda O’Keeffe, author Shoes: A Celebration of Pumps, Sandals, Slippers & More

-

“Stuffed with illuminating illustrations and fresh insights, Pockets will make you reconsider an overlooked but indispensable manifestation of our designed lives. Carlson keeps ferreting out discoveries we didn’t even know we were looking for."Rob Walker, The Art of Noticing

-

"Carlson’s detailed and roving examination of the pocket, a substantial and fascinating book filled with lavish color illustrations, is definitely worth a read — even if it likely won’t fit in anyone’s, well, you know."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"Fascinating insight as to how something as simple as a pocket can influence culture, gender, and society as a whole. Full color images and photos are abundant throughout the text, wonderfully illustrating that which is being discussed. Perfect for readers interested in history and textiles as well as culture, sociology, and gender."Booklist

-

Named a Best/Most Recommended Book by The New Yorker and Publishers Weekly

-

"Fascinating first book… richly illustrated… This erudite, enjoyable book about pockets delivers."Library Journal

-

“[A] colorful look at an everyday piece of fashion that has been routinely underappreciated but never deeply explored.”Inc., "The 15 Best Business Books of 2023"

- On Sale

- Sep 12, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643751542

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use