By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

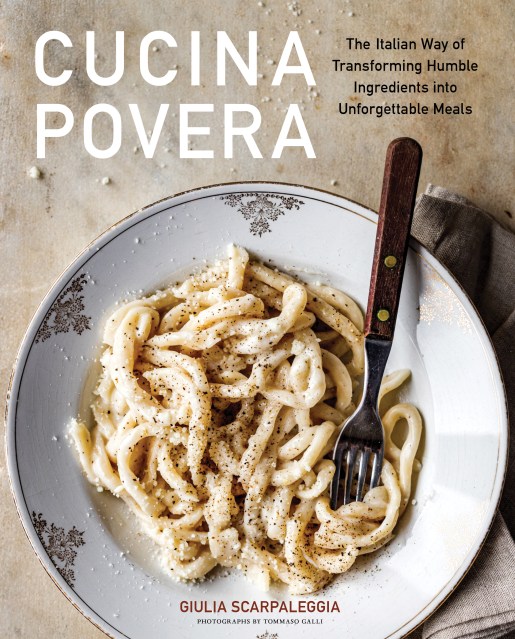

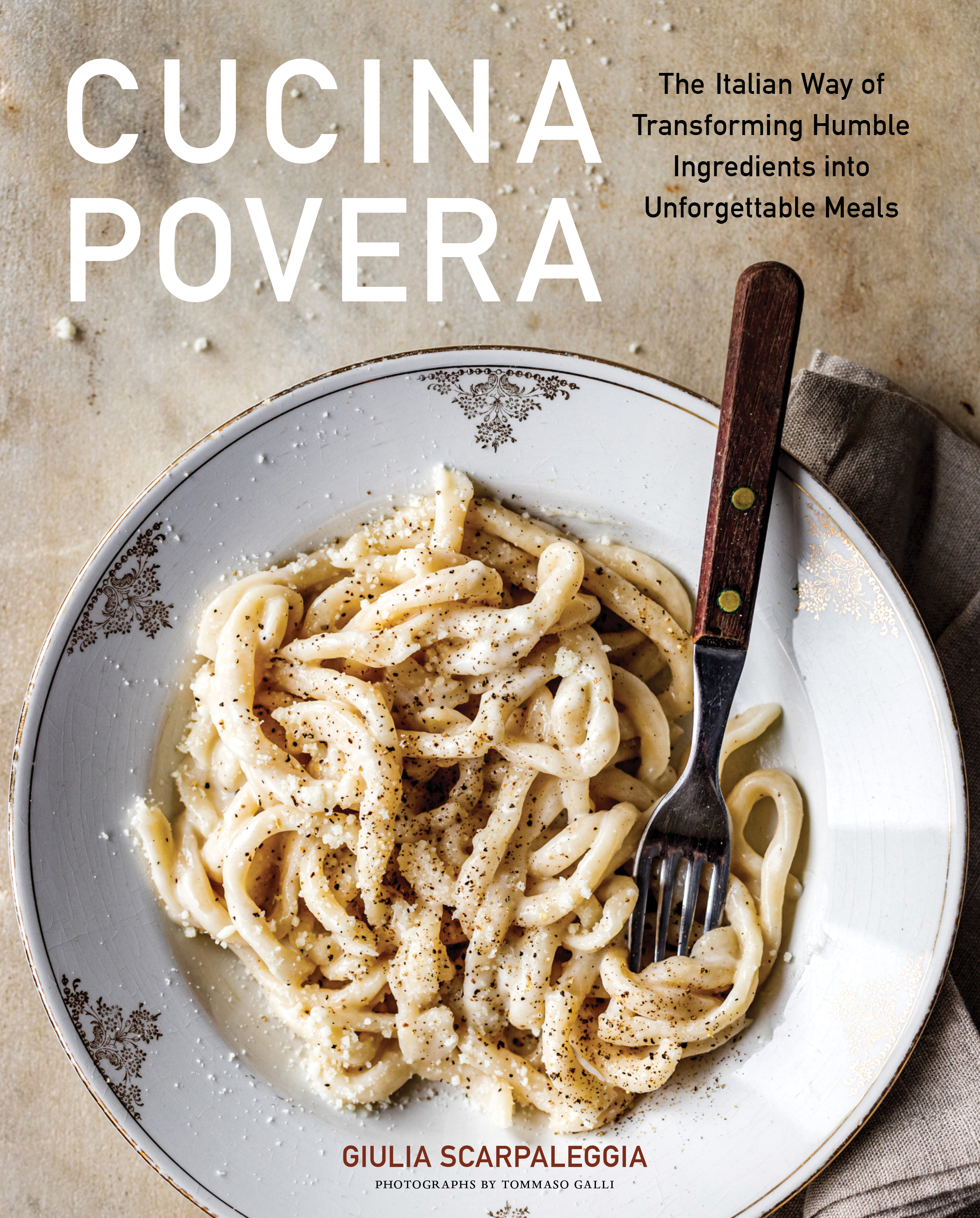

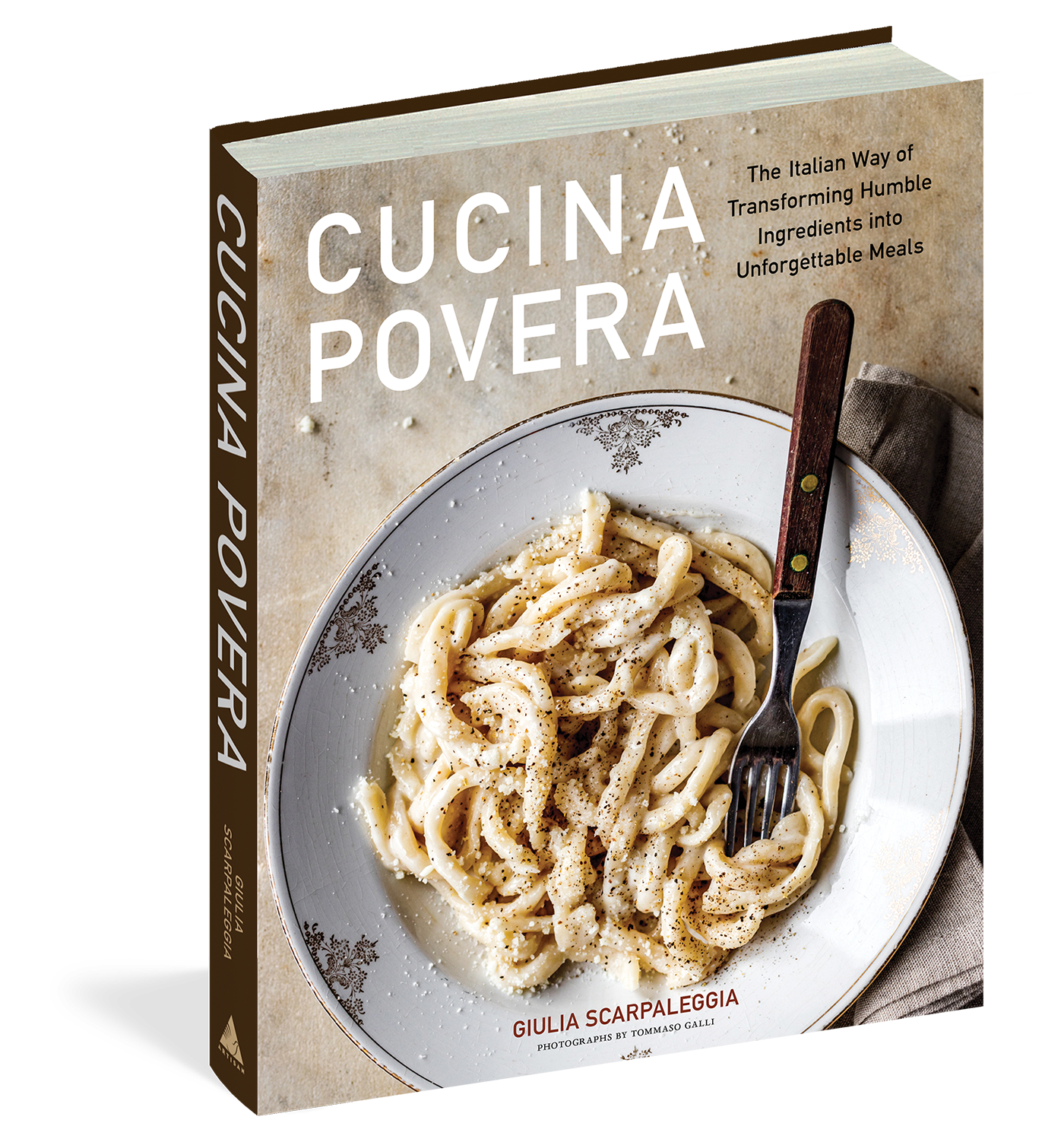

Cucina Povera

The Italian Way of Transforming Humble Ingredients into Unforgettable Meals

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781648290565

Price

$35.00Price

$45.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

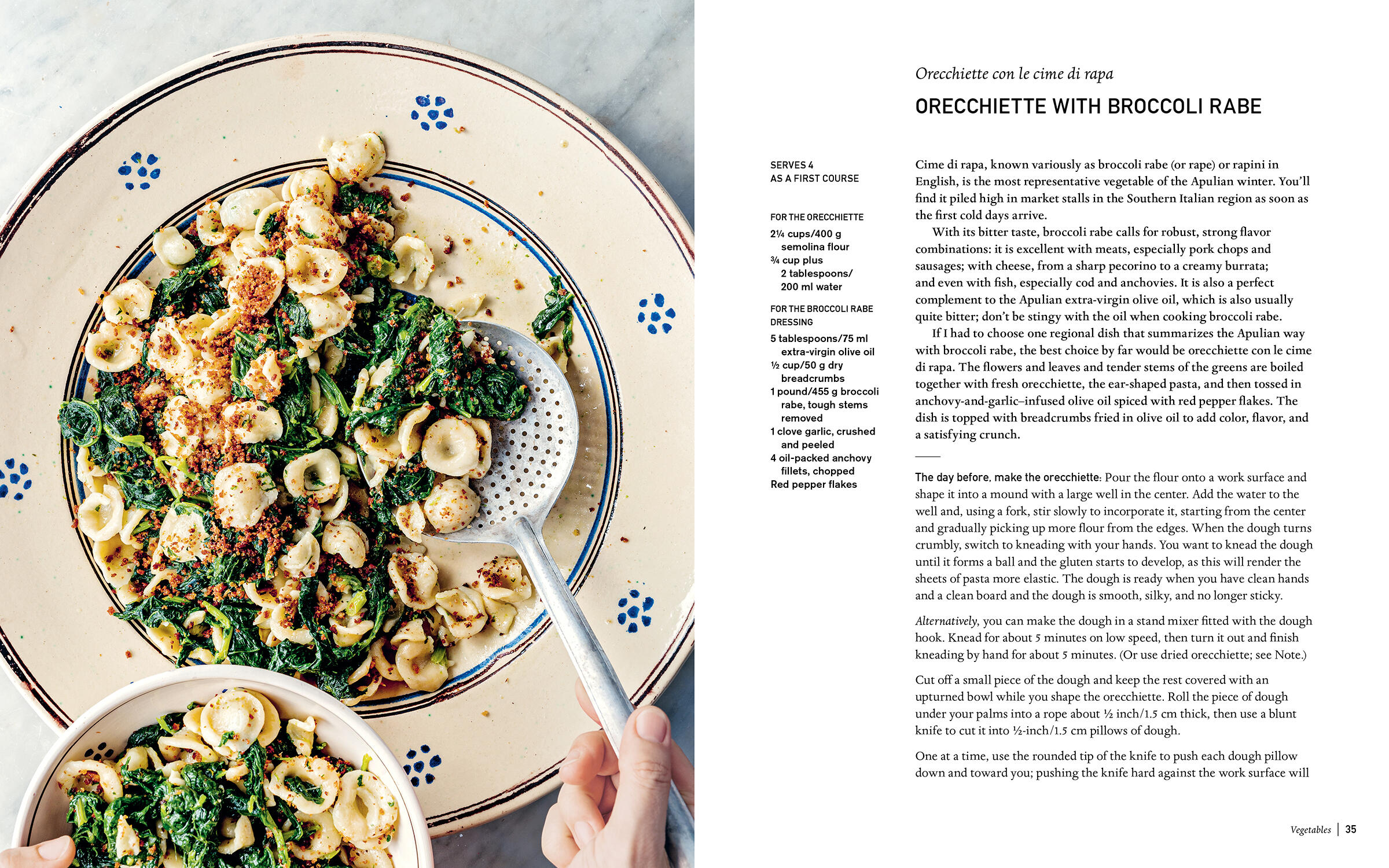

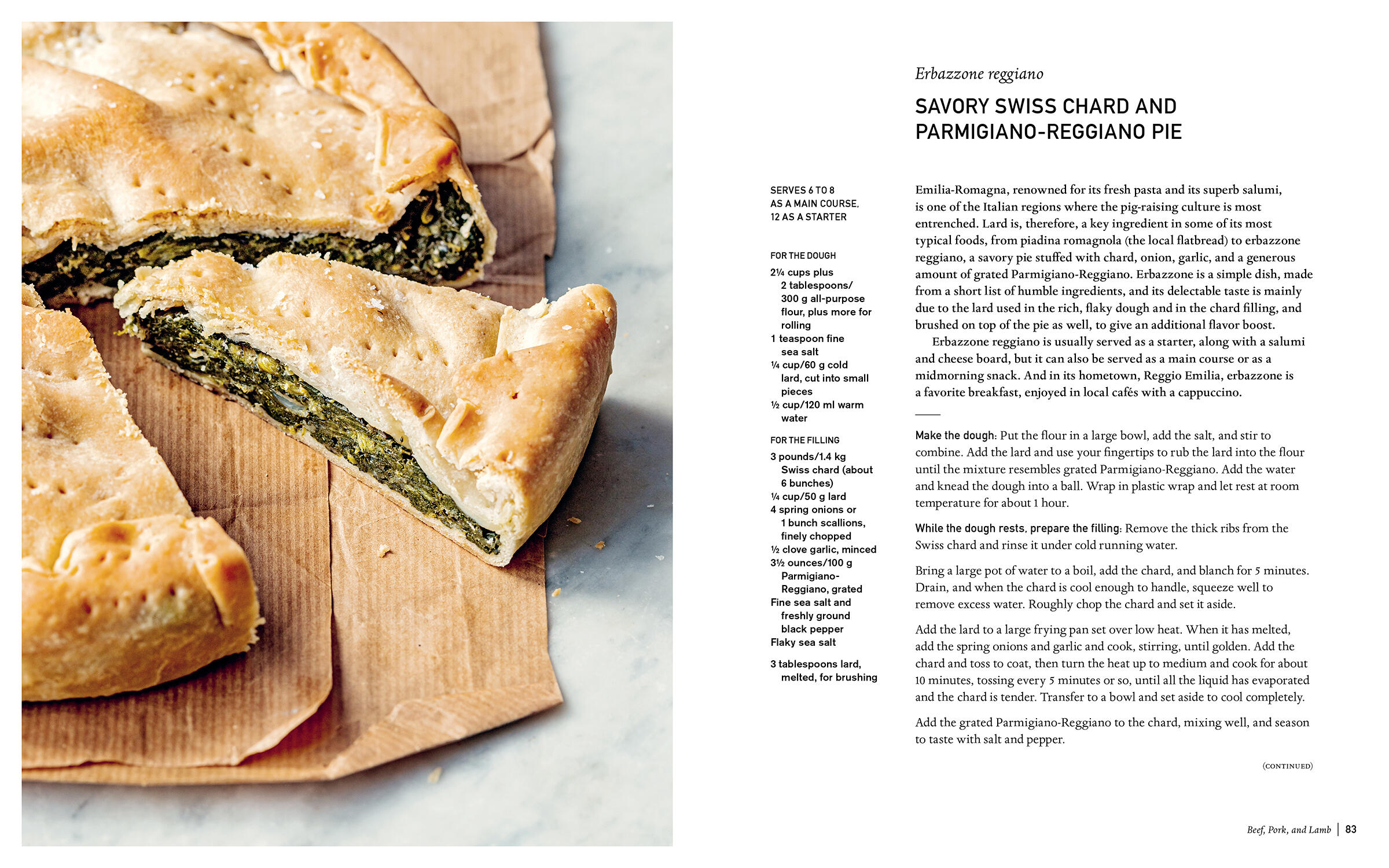

The Italians call it l’arte dell’arrangiarsi, or the “art of making do with what you’ve got.” This centuries-old approach to ingredients and techniques, known as cucina povera, or peasant cooking, reveals the soul of Italian food at its best. It starts with the humblest components—beans and lentils, inexpensive fish and cuts of meat, vegetables from the garden, rice, pasta, leftovers—and through the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the cook, results in unforgettably delicious and satisfying meals. In 100 recipes, Cucina Povera celebrates the best of this tradition, from the author’s favorite, pappa al pomodoro (aka leftover bread and tomato soup), to Florentine Beef Stew, Nettle and Ricotta Gnudi, and Sicilian Watermelon Pudding. Soul satisfying, super healthy, budget-friendly, and easy to make, it’s exactly how so many of us want to eat today.

Genre:

-

“For resourceful home cooks who prefer a farm-to-table approach and Italian flair, this book is a must.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Italian cooks are known for their ability to turn humble ingredients into delicious food. But in the hands (and kitchen) of Tuscan food writer Giulia Scarpaleggia, the art of la cucina povera shines with new allure. Giulia’s deep knowledge of and respect for her native country’s culinary traditions come through in every recipe of this beautifully photographed book.”Domenica Marchetti, author of Preserving Italy

-

“I rarely open a cookbook and want to make several recipes immediately. But it happened! Here is a creative yet practical book with stunning photos. The produce-forward dishes remind me of Cal-Ital cooking in upscale restaurants, yet the ingredients are humble. It’s a cookbook worth adding to your stack.”Dianne Jacob, author of Will Write for Food

-

“Cucina Povera invites you into the heart of Italian home cooking with open arms, and reminds you that good food is—and always has been—simple, sustainable, and cheap. Giulia’s writing is as beautiful and warm as the dishes she makes; this book is an essential resource for any Italian-food lover, but it’ll also make you want to run to the kitchen and cook.”Meryl Feinstein, founder of Pasta Social Club

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use