Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

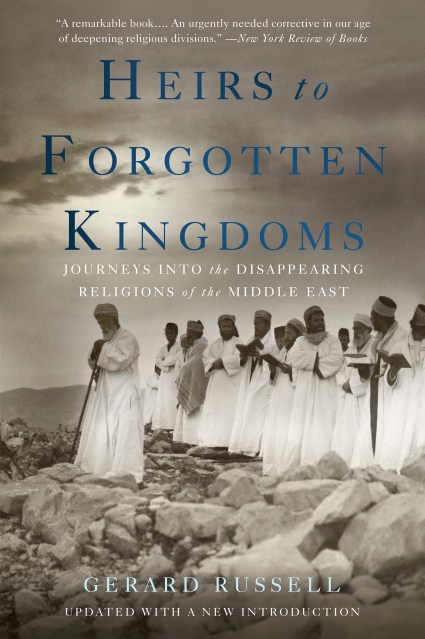

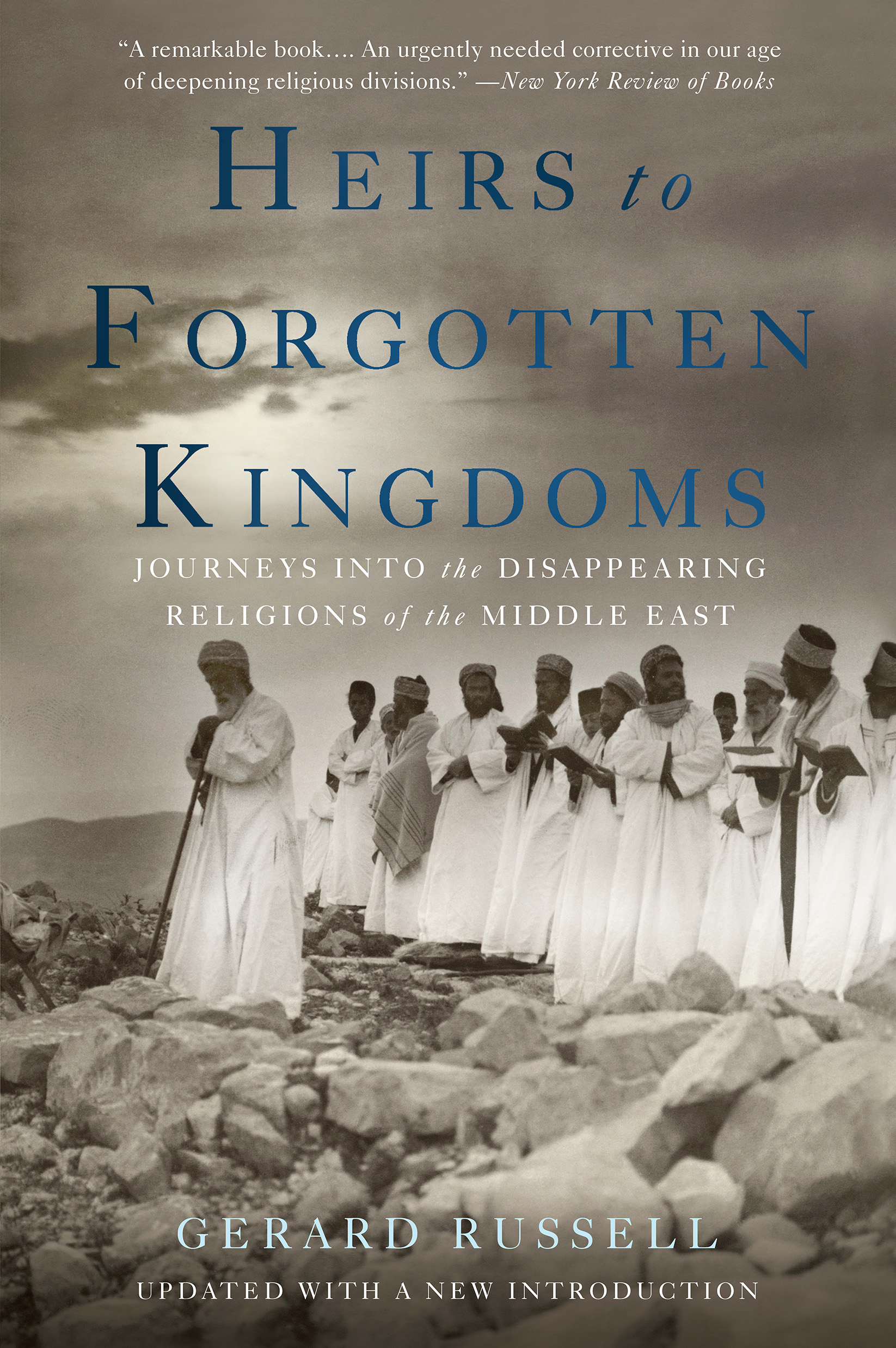

Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms

Journeys Into the Disappearing Religions of the Middle East

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 1, 2015

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465097692

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 1, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms, former diplomat Gerard Russell ventures to the distant, nearly impassable regions where these mysterious religions still cling to survival. He lives alongside the Mandaeans and Ezidis of Iraq, the Zoroastrians of Iran, the Copts of Egypt, and others. He learns their histories, participates in their rituals, and comes to understand the threats to their communities. Historically a tolerant faith, Islam has, since the early 20th century, witnessed the rise of militant, extremist sects. This development, along with the rippling effects of Western invasion, now pose existential threats to these minority faiths. And as more and more of their youth flee to the West in search of greater freedoms and job prospects, these religions face the dire possibility of extinction.

Drawing on his extensive travels and archival research, Russell provides an essential record of the past, present, and perilous future of these remarkable religions.