Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

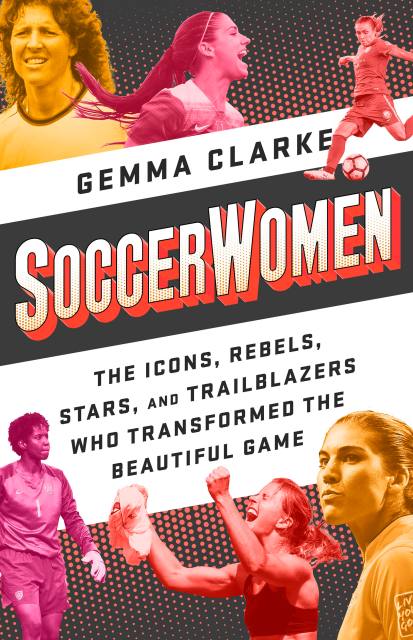

Soccerwomen

The Icons, Rebels, Stars, and Trailblazers Who Transformed the Beautiful Game

Contributors

By Gemma Clarke

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 16, 2019

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589213

Price

$16.99Price

$22.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 16, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Women’s soccer has come a long way. The first organized games on record — which took place three hundred years ago in the Scottish Highlands — were exhibition matches, where single women played against married women while available men looked on, seeking a potential mate.

Today, champions like Mia Hamm, Abby Wambach, Brazil’s Marta and China’s Sun Wen, have inspired girls around the world to pick up the beautiful game for love of the sport. Inevitably, given the hardships and discrimination they face, women who play soccer professionally are so much more than elite athletes. They are survivors, campaigners, political advocates, feminists, LGBTQ activists, working moms, staunch opponents of racial discrimination and inspirational role models for many.

Based on original interviews with over 50 current and former players and coaches, this book celebrates these remarkable women and their achievements against all odds.

Genre:

-

"An excellent, thoughtful read about a topic that has had scandalously little coverage. Women's soccer needs its own heroes and legends. Gemma Clarke is helping to create them. She put her heart into this book, and it shows."Simon Kuper, Financial Times columnist and coauthor of Soccernomics

-

"By tracing women's soccer from its earliest days to the young women breaking out onto the pitch right now through short biographies of some of the best women to play the sport, Clarke provides a comprehensive re-telling of soccer through the words and experiences of the women themselves. This is a book of heroes, but also a book about athletes, who just want to play the game they love. And it is, of course, about triumph in the face of discrimination and diversity. It doesn't take long into the book to start to question why anyone wouldn't choose to support these athletes, forget actively working against them to keep them off the pitch. And not long after that, you'll find yourself cheering these women on, fist-pumping their achievements, and standing in awe of what they done."Jessica Luther, award-winning journalist, co-host of the feminist sports podcast Burn It All Down, and author of Unsportsmanlike Conduct

-

"Where we are now with women's soccer is because of all those who've come before. And my goodness what stories they can tell. In this engrossing read, Gemma Clarke not only shares the battle it has taken to get women onto a football pitch, but then goes on to introduce us to players the world over who we must thank for putting the '2019 Soccerwomen' in a better place. These are stories that have at the very heart of them what it really means when we use such phrases as 'fighting against all odds.' If you want to see what that looks like, over and over again, in its many forms, you'll find it in these quite brilliantly written pages."Rebecca Lowe, NBC Sports Anchor

-

"Soccerwomen charts the remarkable route of the world's most determined female footballers and coaches through fine storytelling and honest testimony. This book is rich with historical detail and personal anecdotes that bring to life the characters, their love of the game, and the way the trailblazers overcame challenges to influence the most popular sport on earth. Gemma Clarke writes with passion, precision and context in this important work. It puts into action the sentiment of the final words: 'To anyone who has ever been told they can't do the thing they love: don't listen. Do it anyway.'"Amy Lawrence, football writer for the Guardian and Observer

-

"You could describe Gemma Clarke's Soccerwomen as a who's who of women's soccer. But it is so much more than that. Her charting the birth of women's soccer in the munitions factories of England to the nuances of its development in the US and the fights for equal rights and pay, better conditions and just the right to play, is peppered with the rich stories of some of the game's most well known names--and those less well known but deserving of a place in the spotlight. Rich storytelling brings to life players sporting achievements and their off field battles, including; homelessness, alcohol abuse, injury, concussion, parenthood, the effects of natural disasters and war and sexuality. An inspirational read that will tell any young or aspiring player going through a difficult time that they can make it and they are not alone."Suzanne Wrack, women's soccer correspondent for The Guardian

-

"Long overdue...Younger readers will be outraged to discover how often men have used false claims about women's bodies to deny women the right to play, or to play as equals. There is still a long way to go, particularly in terms of equal pay-but, as Clarke so capably shows, we've come a long way, too."Booklist