By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

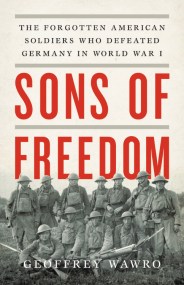

The Fall of the Ottomans

The Great War in the Middle East

Contributors

By Eugene Rogan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 10, 2015

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465056699

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 10, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

By 1914 the powers of Europe were sliding inexorably toward war, and they pulled the Middle East along with them into one of the most destructive conflicts in human history. In The Fall of the Ottomans, award-winning historian Eugene Rogan brings the First World War and its immediate aftermath in the Middle East to vivid life, uncovering the often ignored story of the region's crucial role in the conflict. Unlike the static killing fields of the Western Front, the war in the Middle East was fast-moving and unpredictable, with the Turks inflicting decisive defeats on the Entente in Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, and Gaza before the tide of battle turned in the Allies' favor. The postwar settlement led to the partition of Ottoman lands, laying the groundwork for the ongoing conflicts that continue to plague the modern Arab world. A sweeping narrative of battles and political intrigue from Gallipoli to Arabia, The Fall of the Ottomans is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the Great War and the making of the modern Middle East.

-

"A remarkably readable, judicious and well-researched account of the Ottoman war in Anatolia and the Arab provinces."Mark Mazower, Financial Times

-

"[An] intricately worked but very readable account of the Ottoman theocracy's demise.... This is an extraordinary tale and Rogan recounts it well."New York Times

-

"The book is not only exact and readable but also has the elements of a thriller and thus is all the more remarkable in view of its thoroughness in covering a linguistically and historically difficult subject."Wall Street Journal

-

"To have written a page-turner as well as an accurate and comprehensive history of the Ottoman struggle for survival is a remarkable achievement."Wall Street Journal

-

"This engrossing history unfolds in the Middle Eastern theatre of the First World War, capturing the complex array of battles, brutalities, and alliances that brought down the six-hundred-year-old Ottoman Empire.... Rogan argues that the empire's ultimate demise was the result not of losing the war but of a clumsily negotiated peace. His balanced narrative unearths many seeds of current conflicts."New Yorker

-

"[Rogan's] account is geopolitical and military writing at its best - taut, anecdotal and extraordinarily researched. A tangled story, to be sure, one that both commands and rewards the reader's attention."Washington Times

-

"The Fall of the Ottomans is a remarkably lucid and accessible work of history, involving a large cast of contradictory and complex characters.... Telling quotations from diplomats, field commanders, and ordinary soldiers of all the combatants lend the narrative a powerful sense of immediacy."The Daily Beast

-

"[An] assured account.... The book stands alongside the best histories."Economist

-

"Rogan has written an impressively sound and fair-minded account of the fall of the Ottoman Empire."Max Hastings, Sunday Times (UK)

-

"A comprehensive, lucid and revealing history.... This book will surely become the definitive history of the war."The Times (UK)

-

"[A] masterly history of the Ottoman empire in its final years.... Eugene Rogan has written a meticulously researched, panoramic and engrossing history. The book is essential reading for understanding the evolution of the modern Middle East and the root causes of nearly all the conflicts that now plague the area. The Fall of the Ottomans is an altogether splendid work of historical writing."Ali A. Allawi, The Spectator (UK)

-

"A timely and capacious history which leaves the over-trodden Flanders mud and football truces in favour of the various campaigns--at best imperfectly understood, at worst woefully unfamiliar--which the Allies waged in the Middle East. It's in the former Ottoman lands, traumatised by war, sectarianism and repression, that the legacies of the Great War continue to be grievously felt.... Here's a book whose instructive geopolitical relevance should be immediately apparent.... [A] compelling and brilliant book."Sunday Telegraph (UK)

-

"Admirable and thoroughly researched.... A comprehensive history of World War I in the Middle East."New York Review of Books

-

"As the Middle East is collapsing all around us, if you wanted to know where it all began and when, read this great book by a great Oxford historian."Fareed Zakaria GPS, Book of the Week

-

"Eugene Rogan has given us an absorbing history of the war's principal military and political battles in the Middle East through the eyes of those who fought them. Weaving together accounts of the horrors of life in the trenches with those on the home front, he exposes the deadly dynamic emerging between the two--from the disastrous Ottoman attempt to invade Russia to the horrors of the Armenian deportations, and from the British invasion to the Arab revolt and the empire's final defeat and partition."Mustafa Aksakal, Georgetown University

-

"A fantastic, readable, and much needed study of the most chronically neglected of all of the Great War's participants: the Ottoman Empire. Informative and enlightening."Alexander Watson, author of Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I

-

"This is a gripping, masterful account of World War One in the Middle East from the vantage point of the Ottoman Empire.... Combining magisterial scholarship with a keen sense of drama and lively narrative style, it tells a grim story but a fascinating one.... If you want to understand the underlying causes of conflict and violence in the Middle East in the last century, you will not find a better book."Avi Shlaim, author of The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World

-

"This book opens up a window on vital chapters in the shaping of the Middle East as well as the history of the Great War, bringing together vivid personal details with a broad historical panorama of human suffering and heroism, the incompetence and folly of the general staffs, and the scheming of the great powers."Rashid Khalidi, author of Resurrecting Empire: Western Footprints and America's Perilous Path in the Middle East

-

"Thoroughly researched and elegantly written by one of the leading experts on the region, The Fall of the Ottomans reminds us that the 1914-18 conflict was truly a world war with huge and continuing consequences. No one is better equipped than Eugene Rogan to handle the course and impact of the war in the Middle East and he does a superb job, telling a complex and multifaceted story with great clarity, understanding, and compassion. This timely and important work restores the Middle East to its rightful place in the history of the Great War."Margaret MacMillan, author of The War That Ended Peace: The Road to1914

-

"Thrilling, superb, and colorful, Eugene Rogan's The Fall of the Ottomans is brilliant storytelling. Filled with flamboyant characters, impeccable scholarship that illuminates the neglected Near Eastern theater of WWI--showing how the Ottomans managed repeatedly to defeat the Allies--and revelatory analysis that explains the modern Mideast, The Fall of the Ottomans is truly essential but also truly exciting reading."Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Jerusalem: The Biography

-

"Eugene Rogan has written a meticulously researched, panoramic, and engrossing history of the final years of the Ottoman Empire. This book is essential reading for understanding the evolution of the modern Middle East and the root causes of nearly all the conflicts that now plague the area. An altogether splendid work of historical writing."Ali Allawi, author of The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use