By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

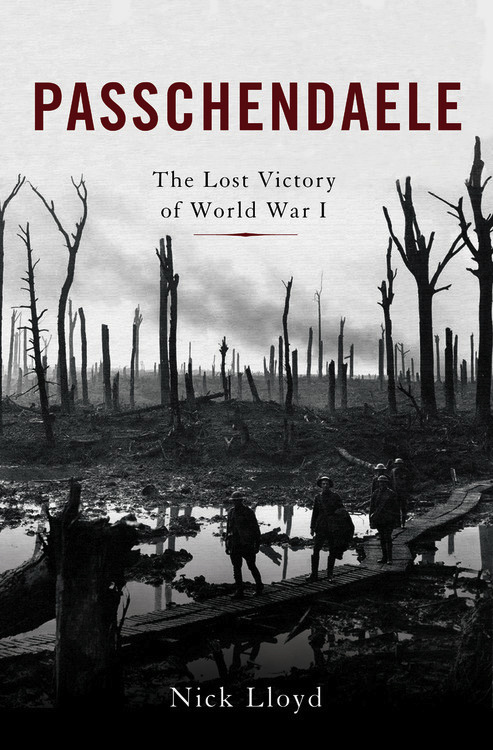

Passchendaele

The Lost Victory of World War I

Contributors

By Nick Lloyd

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 23, 2017

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465094776

Price

$42.00Format

Format:

- Hardcover $42.00

- ebook $19.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 23, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Passchendaele. The name of a small, seemingly insignificant Flemish village echoes across the twentieth century as the ultimate expression of meaningless, industrialized slaughter. In the summer of 1917, upwards of 500,000 men were killed or wounded, maimed, gassed, drowned, or buried in this small corner of Belgium.

On the centennial of the battle, military historian Nick Lloyd brings to vivid life this epic encounter along the Western Front. Drawing on both British and German sources, he is the first historian to reveal the astonishing fact that, for the British, Passchendaele was an eminently winnable battle. Yet the advance of British troops was undermined by their own high command, which, blinded by hubris, clung to failed tactics. The result was a familiar one: stalemate. Lloyd forces us to consider that trench warfare was not necessarily a futile endeavor, and that had the British won at Passchendaele, they might have ended the war early, saving hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lives. A captivating narrative of heroism and folly, Passchendaele is an essential addition to the literature on the Great War.

-

"Red Cross files across western Europe. The German army's terrible suffering is duly explored, as well as that of Canadian and Anzac infantrymen. Published on the eve of Passchendaele's 100th anniversary, the book is harrowing but necessary."Observer

-

"Extensively researched... demonstrate[s] the war's sheer and utter waste of life and resources even as the old mainland Europe monarchical order brought about its own demise."New York Journal of Books

-

"[Lloyd] confirms his position among the best young scholars of WWI in this comprehensively researched, convincingly presented analysis of the still-controversial 1917 battle of Passchendaele. [His] thesis is controversial, but his scholarship makes it impossible to dismiss."Publishers Weekly

-

"Detailed and compelling... There will be other books about Third Ypres this year, but it's unlikely that any of them will be better-researched, more intelligent or fairer than this one. Without in any way minimising the awfulness of the battle, Lloyd makes its inception and course comprehensible. Both as narrative and analysis, this book is masterly."The Scotsman

-

"[Lloyd] retells the story of this infamous conflict with fresh knowledge and newly available materials, including letters, diaries, memoirs, and official reports from both British and German perspectives."Library Journal

-

."[Lloyd's] narrative of the campaign is superb and written with clarity and dispassion... [he] has done his research thoroughly."The Times

-

"Lloyd's research is superb; the book is well-illustrated with photographs and maps; he brings the battle and its political context vividly to life... this is in almost every respect a model of what a work of military history should be, and is now perhaps the definitive account of this phase of the war on the Western Front."Daily Telegraph

-

"An eloquent re-telling of one of the First World War's most mismanaged battles. Lloyd movingly recounts the ordeal of German and British infantry in the mud and blood of Passchendaele."Alexander Watson, author of Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I