By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

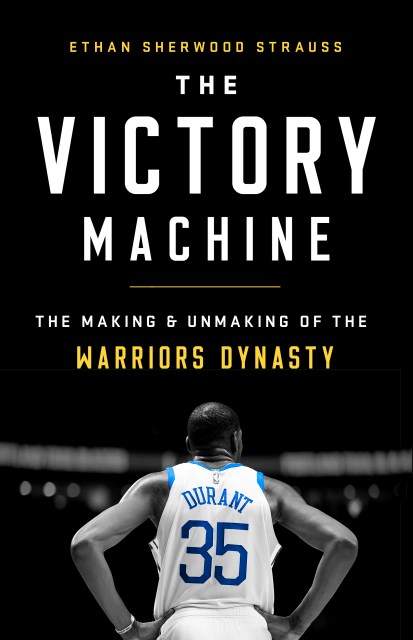

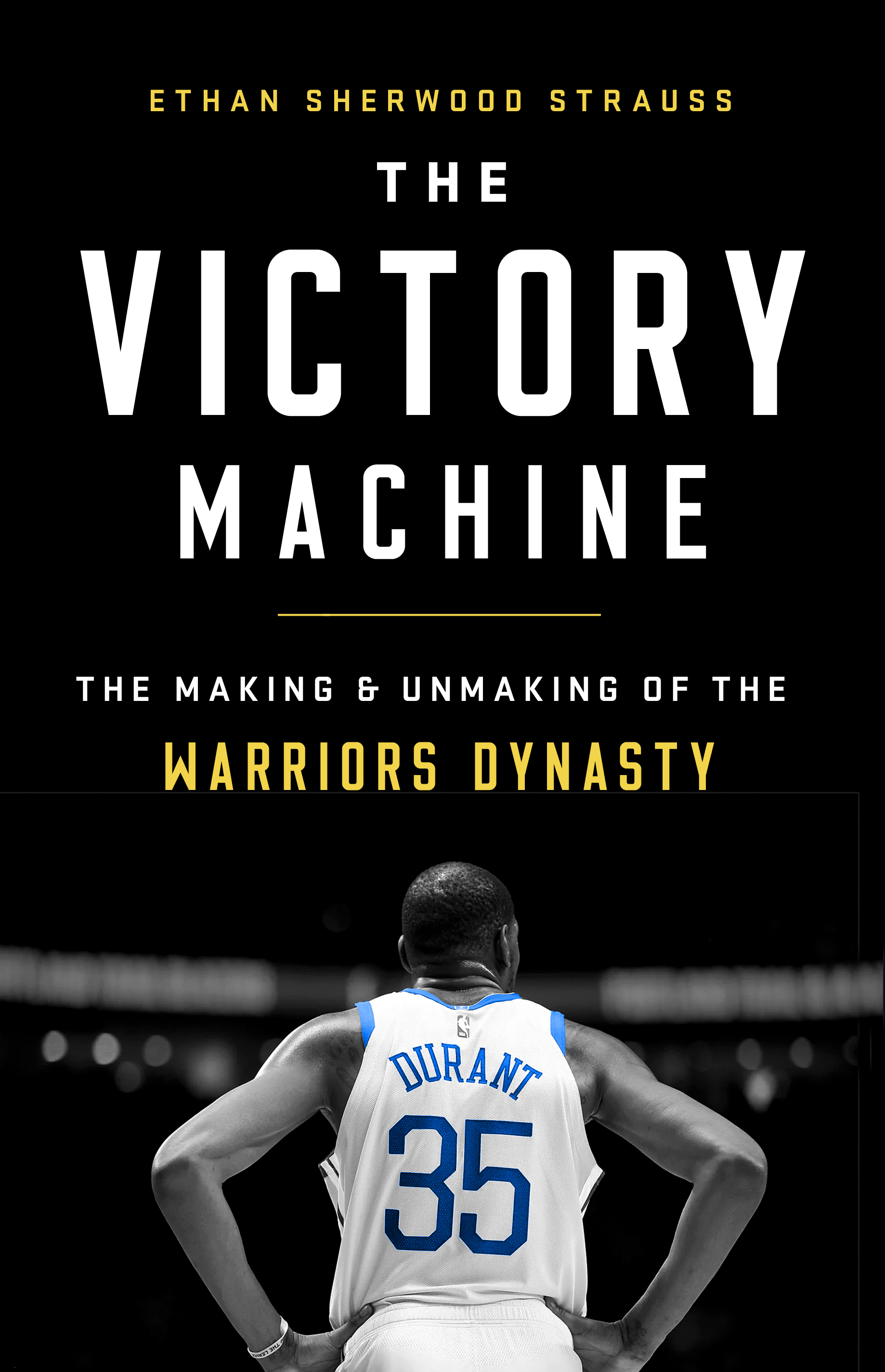

The Victory Machine

The Making and Unmaking of the Warriors Dynasty

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541736214

Price

$12.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Golden State Warriors dominated the NBA for the better part of a decade. Since the arrival of owner Joe Lacob, they won more championships and sold more merchandise than any other franchise in the sport. And in 2019, they opened the doors on a lavish new stadium.

Yet all this success contained some of the seeds of decline. Ethan Sherwood Strauss’s clear-eyed exposé reveals the team’s culture, its financial ambitions and struggles, and the price that its players and managers have paid for all their winning. From Lacob’s unlikely acquisition of the team to Kevin Durant’s controversial departure, Strauss shows how the smallest moments can define success or failure for years.

And, looking ahead, Strauss ponders whether this organization can rebuild after its abrupt fall from the top, and how a relentless business wears down its players and executives. The Victory Machine is a defining book on the modern NBA: it not only rewrites the story of the Warriors, but shows how the Darwinian business of pro basketball really works.

-

"While Strauss clearly loves the sport, he also treats the N.B.A. as a reflection of the 'Darwinian contest' prized by American society...[he] offers insights into how power gets played out in personalities--the motivations, insecurities, and over-all vibe of people who are often insulated from judgment."The New Yorker

-

"Strauss skillfully captures a team peaking as change is taking place all around them, and pulls the curtain aside on the often unsavory realities of what it means to succeed in the NBA."Library Journal

-

What Ethan Strauss does best is to dispense with the niceties and to cut to the core. He's done it again with The Victory Machine, an unvarnished inside account of the Golden State Warriors, from the driven, resolute owner who bought them to the capricious, conflicted superstar who ultimately left them. A must-read for NBA fans.Jackie MacMullan, senior ESPN writer and Hall of Fame basketball commentator

-

"The Victory Machine is The Breaks of the Game of its era. Strauss pulls the curtain back to reveal the ambitions, insecurities, and riches that propel one of the most interesting sports leagues in the world. Most sports books are either idea-driven or character-driven-but Strauss has accomplished both. This is a book I'll come back to again and again for its insight and wit."Kevin Arnovitz, NBA writer, ESPN The Magazine

-

"The Victory Machine isn't a romantic look at the Golden State Warriors dynasty, but it gets to the human core of success and asks the reader to question everything he or she knew about sports."Bomani Jones, cohost of High Noon

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use