By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

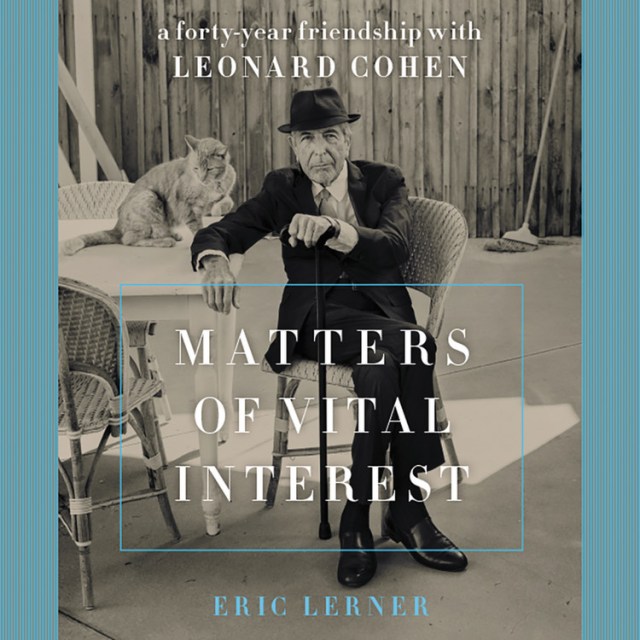

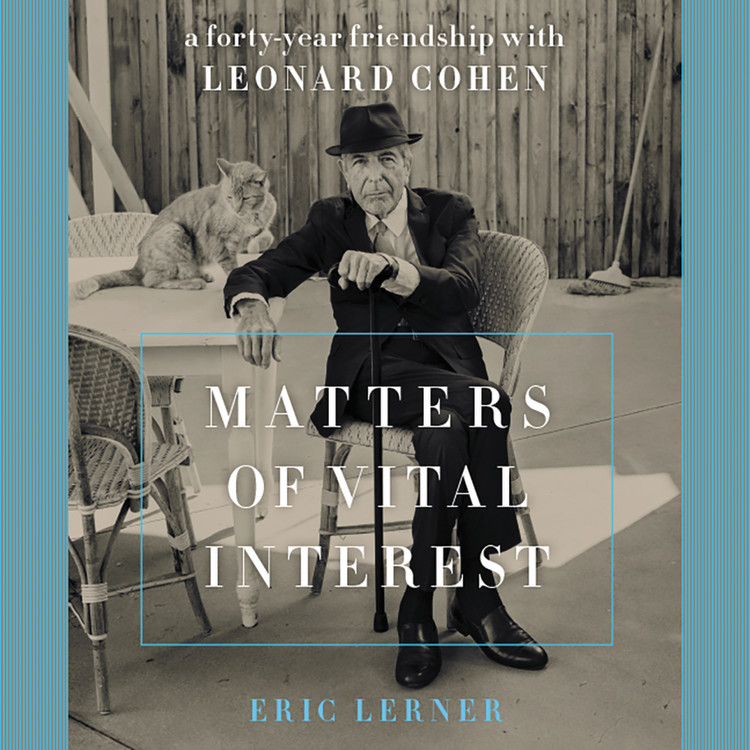

Matters of Vital Interest

A Forty-Year Friendship with Leonard Cohen

Contributors

By Eric Lerner

Read by William Dufris

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 16, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549173936

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 16, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Leonard Cohen passed away in late 2016, leaving behind many who cared for and admired him, but perhaps few knew him better than longtime friend Eric Lerner. Lerner, a screenwriter and novelist, first met Cohen at a Zen retreat forty years earlier. Their friendship helped guide each other through life’s myriad obstacles, a journey told from a new perspective for the first time.

Funny, revealing, self-aware, and deeply moving, Matters of Vital Interest is an insightful memoir about Lerner’s relationship with his friend, whose idiosyncratic style and dignified life was deeply informed by his spiritual practices. Lerner invites readers to step into the room with them and listen in on a lifetime’s ongoing dialogue, considerations of matters of vital interest, spiritual, mundane, and profane. In telling their story, Lerner depicts Leonard Cohen as a captivating persona, the likes of which we may never see again.

-

"Matters of Vital Interest is a portrait of a decades-long friendship, and the vision of Leonard Cohen that emerges from it is much like the persona he invents in his songs--seductive, knowing, hyper-articulate, not always likable but always fascinating. More than a foil, Lerner is the singer's partner in crime, spiritual questing, and, until Leonard Cohen's death, sheer survival. They are brothers, and this is their story, told from the heart."--Anthony DeCurtis, author of Lou Reed: A Life

-

"A remarkably intimate and insightful portrait of one of the world's greatest songwriters--but more than that, a genuine and moving chronicle of friendship, spiritual aspiration, aging, and love."--Alan Light, author of The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of "Hallelujah"

-

"An affectionate, closely observed memoir.... A sensitive portrait of a sly, charming, complicated man."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Lerner's tender, moving memoir reveals Cohen as a devoted friend and father, a side of him not often seen in public."Publishers Weekly

-

"[Matters of Vital Interest] is wonderful...There is a lot of beauty in this book, the beauty that exists between two old friends who love and understand one another."New York Journal of Books

-

"An entertaining memoir...[and] a poignant account of a friendship and the last days of a remarkable life."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use