Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Mummy Darlings

A Glorious Guinness Girls Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 18, 2023

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538724514

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 18, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

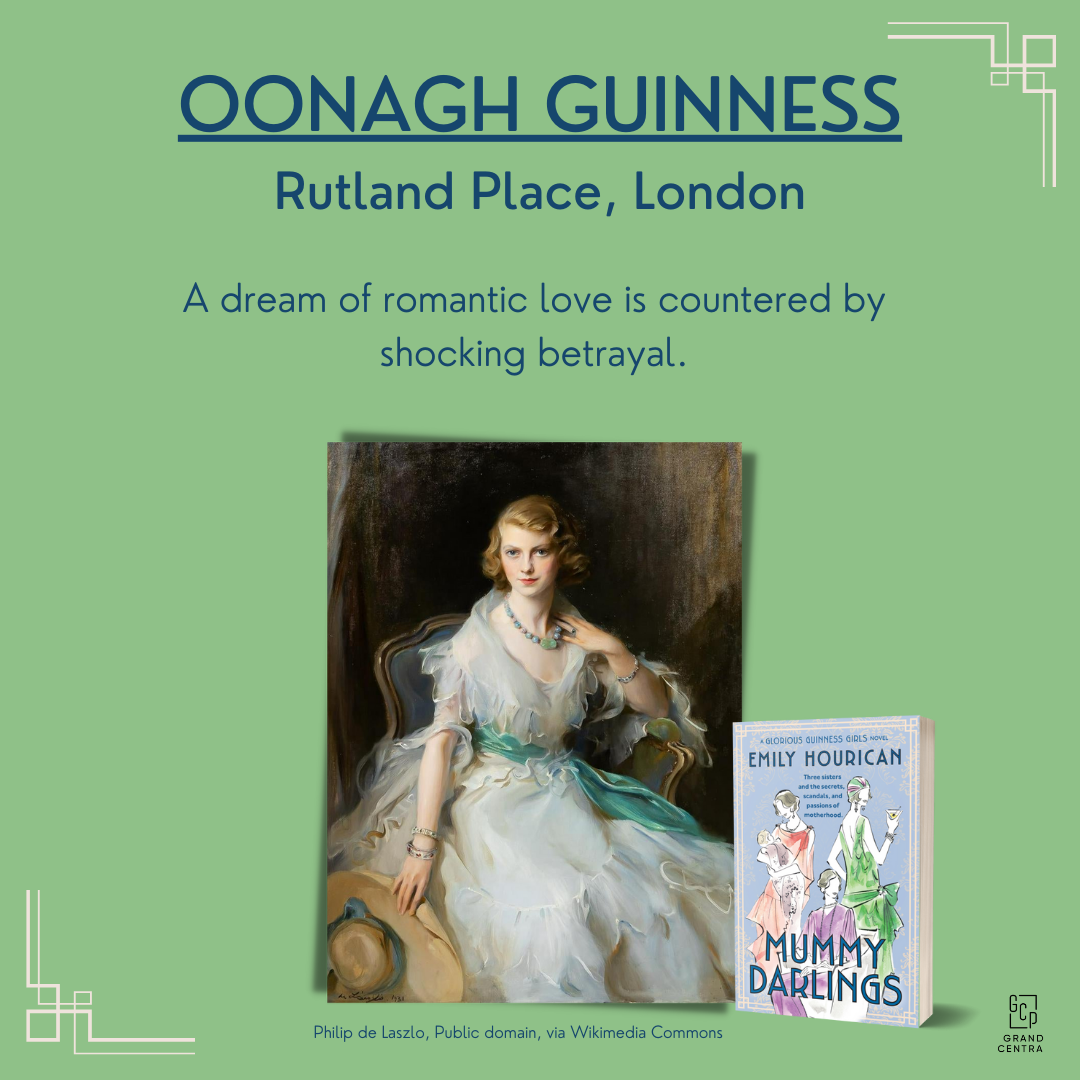

It's the dawn of the 1930s and the three privileged Guinness sisters, Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh, settle into becoming wives and mothers: Aileen in Luttrellstown Castle outside Dublin, Maureen in Clandeboye in Northern Ireland, and Oonagh in Rutland Place in London.

But while Britain becomes increasingly politically polarized, Aileen, Maureen and Oonagh discover conflict within their own marriages.

Oonagh's dream of romantic love is countered by her husband's lies; the intense nature of Maureen's marriage means passion, but also rows; while Aileen begins to discover that, for her, being married offers far less than she had expected.

Meanwhile, Kathleen, a housemaid from their childhood home in Glenmaroon, travels between the three sisters, helping, listening, watching–even as her own life brings her into conflict with the clash between fascism and communism.

As affairs are uncovered and secrets exposed, the three women begin to realize that their gilded upbringing could not have prepared them for the realities of married life, nor for the scandals that seem to follow them around.

Genre:

-

"A great selection for book clubs!"Booklist

LISTEN TO AN AUDIO EXCERPT

MEET THE GUINNESS GIRLS!

Download the Book Club Kit

Including discussion questions, an author q&a, and delicious Guinness recipes for your book club!

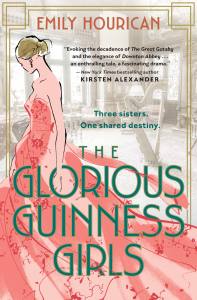

AND DON’T MISS THE FIRST GLORIOUS GUINNESS GIRLS NOVEL

From London to Ireland during the 1920s, this glorious, gripping, and richly textured story takes us to the heart of the remarkable real-life story of the Guinness Girls—perfect for fans of Downton Abbey and Julian Fellowes’ Belgravia.

Descendants of the founder of the Guinness beer empire, they were the toast of 1920s high society, darlings of the press, with not a care in the world. But Felicity knows better. Sent to live with them as a child because her mother could no longer care for her, she grows up as the sisters’ companion. Both an outsider and a part of the family, she witnesses the complex lives upstairs and downstairs, sees the compromises and sacrifices beneath the glamorous surface. Then, at a party one summer’s evening, something happens that sends shock waves through the entire household.

Inspired by a remarkable true story and fascinating real events, The Glorious Guinness Girls is an unforgettable novel about the haves and have-nots, one that will make you ask if where you find yourself is where you truly belong.

Descendants of the founder of the Guinness beer empire, they were the toast of 1920s high society, darlings of the press, with not a care in the world. But Felicity knows better. Sent to live with them as a child because her mother could no longer care for her, she grows up as the sisters’ companion. Both an outsider and a part of the family, she witnesses the complex lives upstairs and downstairs, sees the compromises and sacrifices beneath the glamorous surface. Then, at a party one summer’s evening, something happens that sends shock waves through the entire household.

Inspired by a remarkable true story and fascinating real events, The Glorious Guinness Girls is an unforgettable novel about the haves and have-nots, one that will make you ask if where you find yourself is where you truly belong.