By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

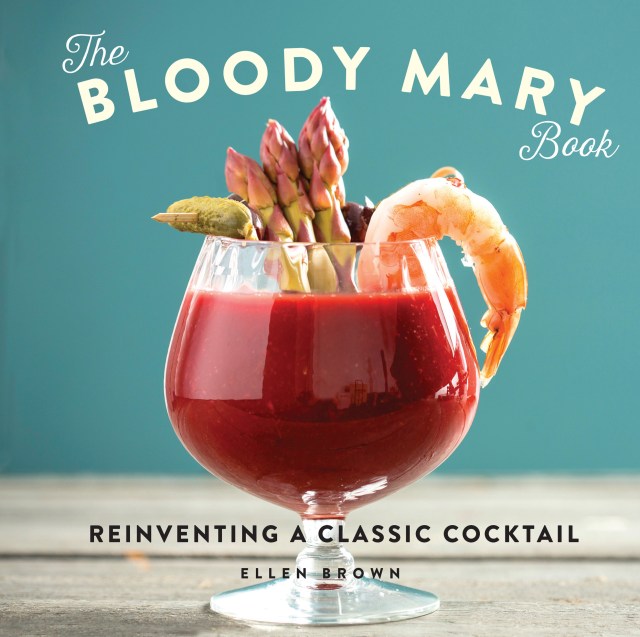

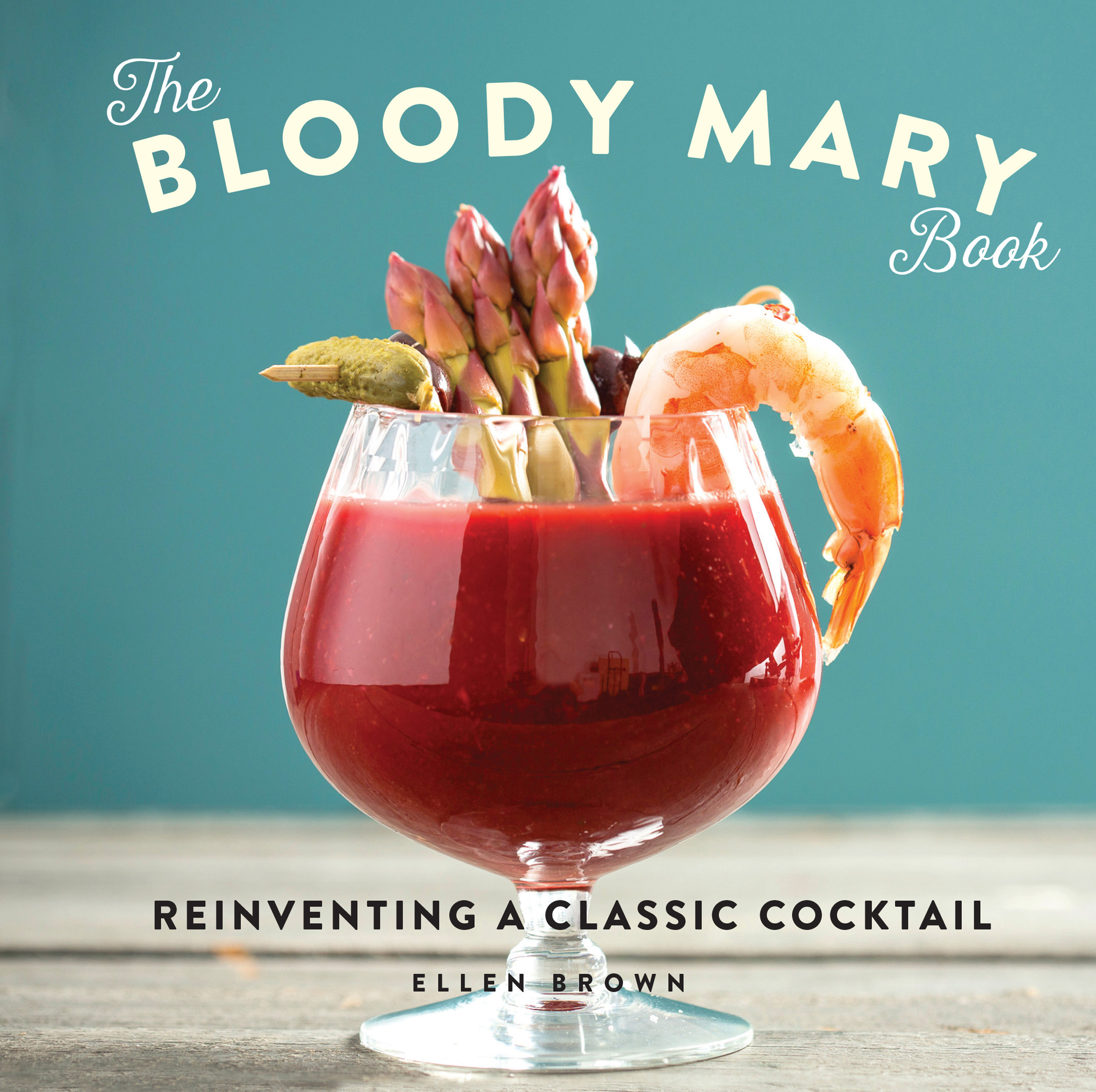

The Bloody Mary Book

Reinventing a Classic Cocktail

Contributors

By Ellen Brown

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 23, 2017

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762461684

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 23, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 65 inventive recipes, the Bloody Mary is rejiggered with a rainbow of garnishes, new flavors, and different liquors. The drinks are a dizzying array of creativity, from the Vegan Mary, which is packed with umami, to a Middle Eastern Mary, adding cumin, coriander, and harissa for an extra bit of spice. Shake up these recipes for the perfect weekend pairing, complete with bar food for a little nosh:

Drinks:

- The Bowling Green Bloody

- The Bloody Maja

- The Gazpacho Mary

Eats:

- Celery Stuffed with Pimiento Cheese

- Smoked Salmon Spread

- Spanish Potato and Sausage Tortilla

And if you don’t have time to whip up a Bloody Mary mix from scratch, no worries: author Ellen Brown has demystified the cream of the crop of store-bought bases that will have you sipping a savory concoction ASAP. Just add your own special twist and a few garnishes. Whatever your fancy, the Bloody Mary is the perfect weekend drink.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use