By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

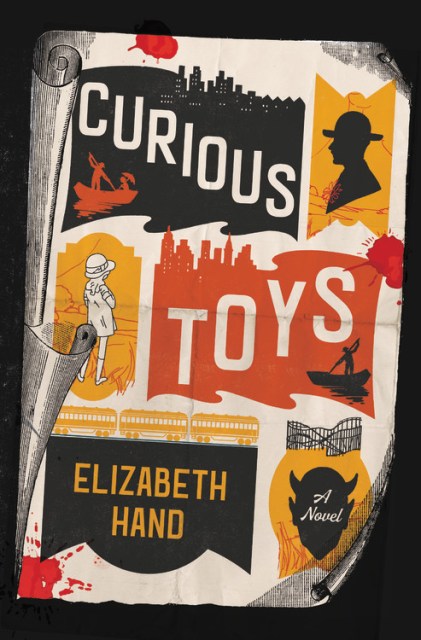

Curious Toys

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2020

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316485913

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the sweltering summer of 1915, Pin, the fourteen-year-old daughter of a carnival fortune-teller, dresses as a boy and joins a teenage gang that roams the famous Riverview amusement park, looking for trouble.

Unbeknownst to the well-heeled city-dwellers and visitors who come to enjoy the midway, the park is also host to a ruthless killer who uses the shadows of the dark carnival attractions to conduct his crimes. When Pin sees a man enter the Hell Gate ride with a young girl, and emerge alone, she knows that something horrific has occurred.

The crime will lead her to the iconic outsider artist Henry Darger, a brilliant but seemingly mad man. Together, the two navigate the seedy underbelly of a changing city to uncover a murderer few even know to look for.

Unbeknownst to the well-heeled city-dwellers and visitors who come to enjoy the midway, the park is also host to a ruthless killer who uses the shadows of the dark carnival attractions to conduct his crimes. When Pin sees a man enter the Hell Gate ride with a young girl, and emerge alone, she knows that something horrific has occurred.

The crime will lead her to the iconic outsider artist Henry Darger, a brilliant but seemingly mad man. Together, the two navigate the seedy underbelly of a changing city to uncover a murderer few even know to look for.

-

ONE OF THE YEAR'S BEST BOOKSLitHub * Chicago Public Library * CrimeReads

-

"Hand--whose masterly oeuvre ranges from the eerie to the horrific, post-punk to magic--delivers another brilliant mystery.... Wonderfully imaginative and richly delivered."Ivy Pochoda, New York Times Book Review

-

"Curious Toys is itself like a carnival ride: alternatively dazzling and terrifying, disorienting and marvelous."Amy Stewart, The Washington Post

-

"Brilliant, bustling . . . While Hand paces her mystery with classic precision, the real reward of Curious Toys lies in its richly textured panorama of Chicago during a crucial period of change, and in its vivid characters."Gary Wolfe, Chicago Tribune

-

"Deliciously creepy . . . Atmospheric . . . Hand's gripping plot mines the era's vagaries with aplomb."Associated Press

-

"[Pin] is a remarkable young sleuth. . . . Curious Toys is a thriller to be savored-tough, funny, strange, and revelatory."Michael Berry, Portland Press Herald

-

"This book contains a rare kind of perfection: Elizabeth Hand's rough, observant magic draws into its circle great historical accuracy, a cross-dressing central protagonist, a wonderfully tender portrait of the great Outsider Artist Henry Darger, a vibrant thriller plot, reflections on gender and its place in civic order, a helpful Ben Hecht, and one of the greatest climactic drop-the-mic moments I've ever read -- and does all this while patiently setting into place the warm emotional armatures that make Curious Toys so moving."Peter Straub

-

"A well-crafted and deliciously unsettling period thriller."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Hand is a mage of the page.... [Curious Toys] will enchant those who like tough-girl protagonists and antiheroes, as well as fans of historical crime fiction."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Curious Toys is wonderful! I stayed up late two nights in a row, transported. It will be catnip for readers who love Chicago, circuses, cross-dressers, and early cinema."Audrey Niffenegger, bestselling author of The Time-Traveler's Wife

-

"[Hand] crafts a gritty and winsome character whose sheer determination to catch a murderer makes this mystery novel whiz by."WBUR

-

"This atmospheric novel will transport you to a world you've never imagined before."Real Simple

-

"Richly imaginative and psychologically complex."Kirkus Reviews

-

"An atmospheric crime novel... A phantasmagoric time trip tailor-made for fans of The Devil in the White City."Publishers Weekly

-

"Glittering and scruffy as its carnival setting, with the deep gravity hold of a rollercoaster."Lauren Beukes, internationally acclaimed author of The Shining Girls and Broken Monsters

-

"The latest novel from genre-crossing master storyteller Elizabeth Hand journeys from thriller territory straight into the heart of horror . . . A richly layered study of horror and sin and fantasy and reality, all in a peculiarly American vein. And it's scary as hell."Chicago Review of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use