By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

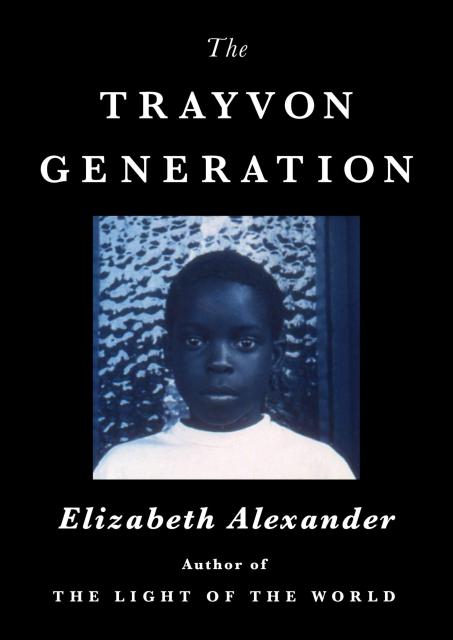

The Trayvon Generation

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 144 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538737903

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $22.00 $28.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $14.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

*Named a Most Anticipated Title of 2022 by TIME magazine, New York Times, Bustle, and more*

In the midst of civil unrest in the summer of 2020 and following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, Elizabeth Alexander—one of the great literary voices of our time—turned a mother's eye to her sons’ and students’ generation and wrote a celebrated and moving reflection on the challenges facing young Black America. Originally published in the New Yorker, the essay incisively and lovingly observed the experiences, attitudes, and cultural expressions of what she referred to as the Trayvon Generation, who even as children could not be shielded from the brutality that has affected the lives of so many Black people.

The Trayvon Generation expands the viral essay that spoke so resonantly to the persistence of race as an ongoing issue at the center of the American experience. Alexander looks both to our past and our future with profound insight, brilliant analysis, and mighty heart, interweaving her voice with groundbreaking works of art by some of our most extraordinary artists. At this crucial time in American history when we reckon with who we are as a nation and how we move forward, Alexander's lyrical prose gives us perspective informed by historical understanding, her lifelong devotion to education, and an intimate grasp of the visioning power of art.

This breathtaking book is essential reading and an expression of both the tragedies and hopes for the young people of this era that is sure to be embraced by those who are leading the movement for change and anyone rising to meet the moment.

-

Praise for The Trayvon Generation:New York Times

"A profound and lyrical meditation on race, class, justice and their intersections with art...Magnificent." -

"Powerful, poignant, and deeply moving. I hope you'll check it out."Michelle Obama, Former First Lady of the United States

-

"A series of meditations on cultural and artistic artifacts that illuminate “the color line”...Alexander is like a cultural archaeologist, dusting off and examining relics and shedding new light on the society that produced them...She brings a poet’s clarity of language to the fraught national discussion."TIME

-

"The book offers historic perspective and poignant observations that make this an urgent and critical read."Jake Tapper, CNN

-

"In Elizabeth Alexander’s beautiful, relevant book, The Trayvon Generation, the poet redefines the proximity of Black identity to loss as an opportunity to create new rituals and a new paradigm...The book offers wisdom, reflection, and reportage with a crystalline precision infused with a powerful, elegant empathy."The Boston Globe

-

"How do you mark your pages when you read a book? Whatever you use, have a lot of them on hand because nearly every other paragraph of The Trayvon Generation contains a sentence or three that you'll want to remember, to re-read, or turn over in your mind...So must-readable, so thoughtful and compelling...you'll want to share with your older teenager and your friends, for discussion."The Philadelphia Tribune

-

"Dr. Alexander is an acclaimed scholar and poet. She's also a superb writer and unusually well-qualified to lead us to meditate and learn about the intersections of art, poetry, history, and race."Dan Rather, journalist and New York Times bestselling author of What Unites Us

-

"The Trayvon Generation is definitely essential reading for every generation."Cosmopolitan

-

"An essential read for our times by the only person who could’ve written it so exquisitely."Ms. Magazine

-

"In a taut, lyrical, and eminently readable volume, Alexander helps the reader make sense of the presents and futures being forged by Black artists who shall inherit the earth and thus have to find ways to delight themselves amid a continual abundance of racialized violence."Vulture

-

“A powerful book which unveils the ways in which race is woven so deeply into the fabric of American culture, and sheds a light on how art can reveal the urgency of this issue.”Town & Country

-

“Electrifying and poignant, The Trayvon Generation sheds light on the role of art as criticism and medicine.”Esquire

-

"Punctuated with gripping pieces of art that complement the text. Each piece is compelling in its own right as they entwine with the representation of human experience that Alexander demonstrates for readers… At its core, this is a powerful treatise on the humanity of Black Americans and how it has been denied, how generations of people have persisted despite that fact, and how it continues to be one of the most pressing issues we face as a nation. A dynamic critique on the sprawling effects of racism and its effects on today’s youth."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

“Poet and memoirist Alexander deftly blends family history and cultural criticism in this bittersweet essay collection on race, memory, and memorialization…Alexander is a thoughtful and eloquent chronicler of racial anxiety and pain.”Booklist (starred review)

-

“Vigorous and inspiring…By capturing the rich spectrum of Black culture in America, Alexander offers hope and instruction for younger generations. The result is a thought-provoking must-read.”Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"A very moving short book that seeks to challenge readers’ assumptions about American society; highly recommended for all libraries and for reading groups."Library Journal (starred review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use