Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

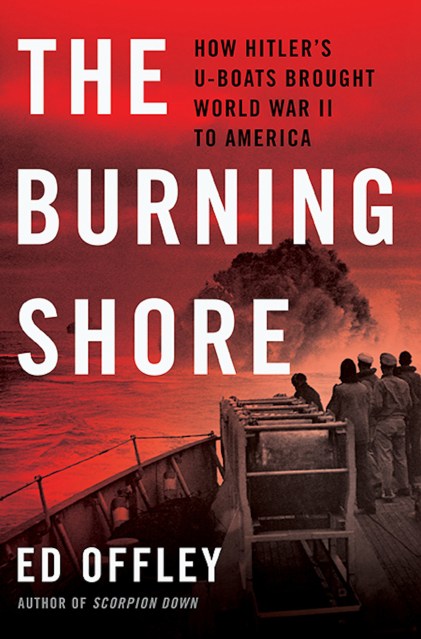

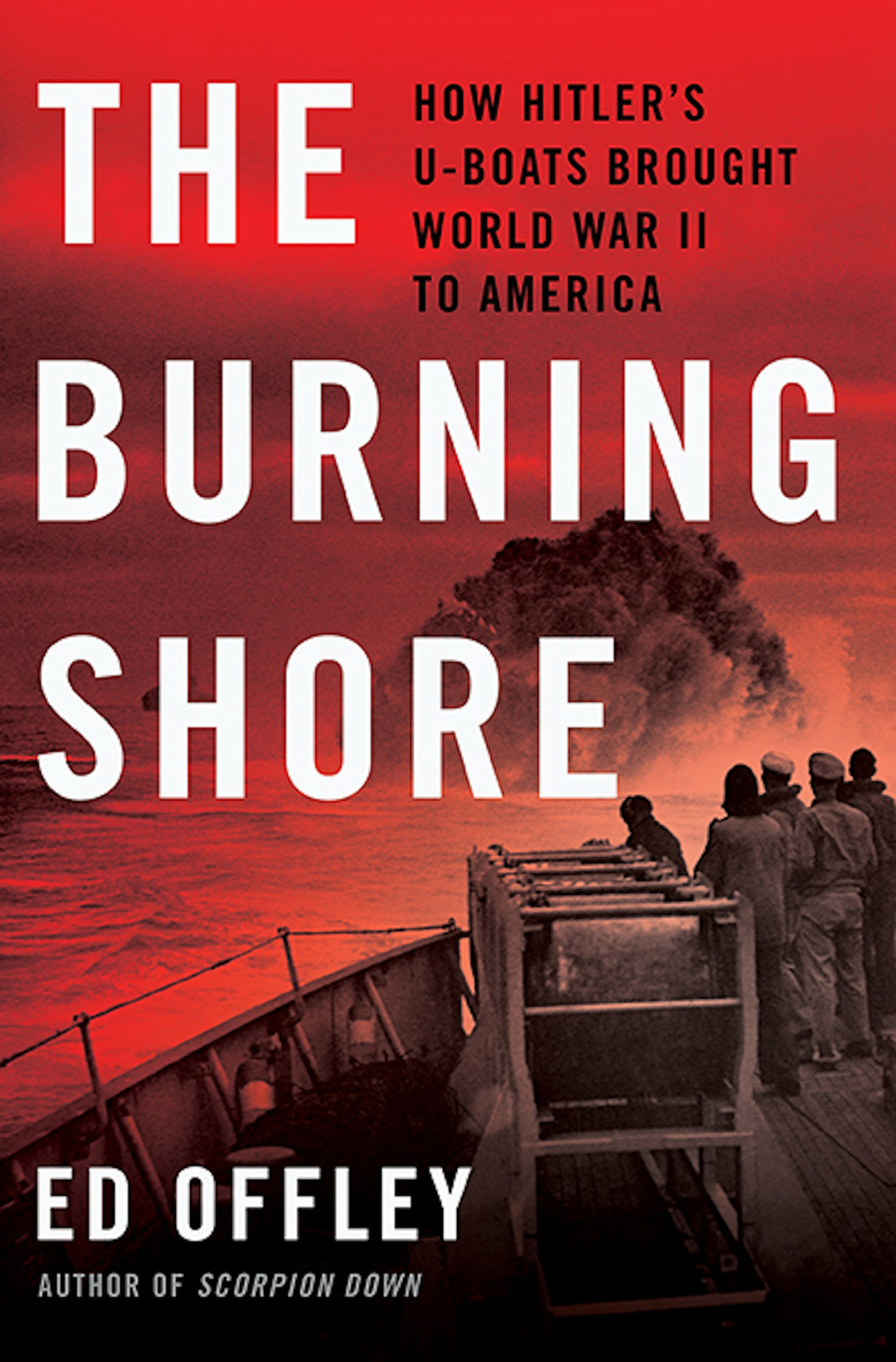

The Burning Shore

How Hitler's U-Boats Brought World War II to America

Contributors

By Ed Offley

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 25, 2014

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465080694

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $48.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 25, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In The Burning Shore, acclaimed military reporter Ed Offley presents a thrilling account of the bloody U-boat offensive along America’s east coast during the first half of 1942, using the story of Degen’s three war patrols as a lens through which to view this forgotten chapter of World War II. For six months, German U-boats prowled the waters off the eastern seaboard, sinking merchant ships with impunity, and threatening to sever the lifeline of supplies flowing from America to Great Britain. Degen’s successful infiltration of the Chesapeake Bay in mid-June drove home the U-boats’ success, and his spectacular attack terrified the American public as never before. But Degen’s cruise was interrupted less than a month later, when U.S. Army Air Forces Lieutenant Harry J. Kane and his aircrew spotted the silhouette of U-701 offshore. The ensuing clash signaled a critical turning point in the Battle of the Atlantic — and set the stage for an unlikely friendship between two of the episode’s survivors.

A gripping tale of heroism and sacrifice, The Burning Shore leads readers into a little-known theater of World War II, where Hitler’s U-boats came close to winning the Battle of the Atlantic before American sailors and airmen could finally drive them away.