By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

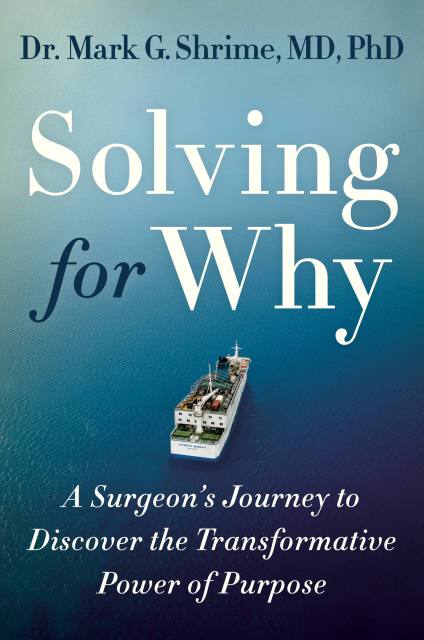

Solving for Why

A Surgeon's Journey to Discover the Transformative Power of Purpose

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 25, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538734162

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 25, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

SOLVING FOR WHY chronicles one man’s journey to find the answer to the biggest of all life’s questions: “Why?” Following a traumatic car accident, Dr. Shrime—the child of Lebanese immigrants fleeing a civil war, who later became a successful practicing surgeon in Boston—found himself compelled to change the course of his life, determined to find meaning and satisfaction even if it meant diverting from America’s idea of “success.” Featuring stories, insights, and research from his own exceptional life and work, SOLVING FOR WHY is the story of Dr. Shrime’s search for—and discovery of—lifelong fulfillment.

Now a global surgeon operating on a hospital ship docked off the coast of West Africa and one of the few global experts on surgery in low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Shrime seeks to impart the wisdom of the lessons he’s learned over the course of his search for a life of true contentment. In the tradition of Dr. Paul Farmer’s To Repair the World, Dr. Atul Gawande’s Better, and Dr. Michele Harper’s The Beauty in Breaking, SOLVING FOR WHY combines personal stories with deep, thoughtful research into the challenges of working in modern medicine in the 21st century and the commodification of work in America.

A story of discovery and transformation, SOLVING FOR WHY seeks to help readers answer the “why” of their own lives and ultimately find joy outside the status quo.

-

"Dr. Mark Shrime is one of the most remarkable humans I’ve ever met. I knew he’d write a wonderful book—I just didn’t expect to dog ear every page and underline so many wonderful thoughts that he puts so well onto the page. His curiosity pushes him to learn more about himself, the world, and why we are here and what we should be doing to live up to our potential. I loved this book and believe it will be widely read and remembered. And I’m so mad I didn’t think of this title first!"Dana Perino, New York Times bestselling author of EVERYTHING WILL BE OKAY

-

"As I read, unable to put this compelling book down, I heard my heart echoing thoughts and questions that arose out of the pages. I discovered in each page a profound perspective and a provoking transparency. I will read it again and again."Barclay Stockett, American Ninja Warrior

-

"I am not sure if I have ever read a book where the author was willing to bare their soul as completely as Dr. Mark Shrime does in this remarkable book. By sharing his life’s complicated journey, he will (or at last should) inspire the rest of us to take a good look at the 'moving sidewalk' of our own lives and figure out if we are going the right direction. I needed and appreciated this push."Jean Becker, New York Times bestselling author of THE MAN I KNEW