By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

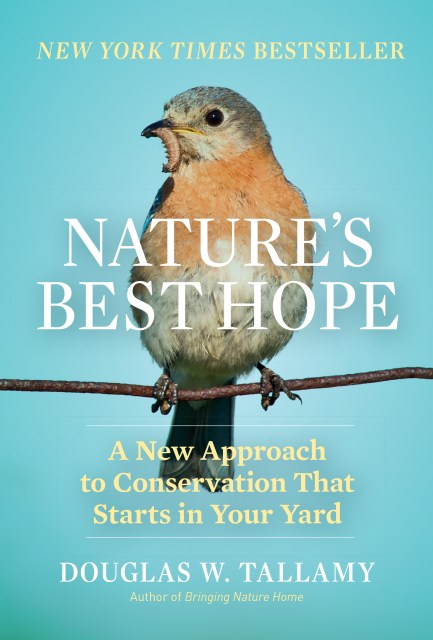

Nature’s Best Hope

A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699005

Price

$30.00Price

$40.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the New York Times bestselling author of Bringing Nature Home comes an urgent and heartfelt call for a new approach to conservation—one that starts in every backyard.

Douglas W. Tallamy’s first book, Bringing Nature Home, awakened thousands of readers to an urgent situation: wildlife populations are in decline because the native plants they depend on are fast disappearing. His solution? Plant more natives. In this new book, Tallamy takes the next step and outlines his vision for a grassroots approach to conservation. Nature’s Best Hope shows how homeowners everywhere can turn their yards into conservation corridors that provide wildlife habitats. Because this approach relies on the initiatives of private individuals, it is immune from the whims of government policy. Even more important, it’s practical, effective, and easy—you will walk away with specific suggestions you can incorporate into your own yard.

If you’re concerned about doing something good for the environment, Nature’s Best Hope is the blueprint you need. By acting now, you can help preserve our precious wildlife—and the planet—for future generations.

“Tallamy lays out all you need to know to participate in one of the great conservation projects of our time. Read it and get started!” —Elizabeth Kolbert, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sixth Extinction

-

“Doug Tallamy lays out all you need to know to participate in one of the great conservation projects of our time. Read it and get started!” B>Elizabeth Kolbert, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sixth ExtinctionMaine Home Garden News “Tallamy strikes the perfect compromise between fear and optimism… a must read for anyone who cares about the future of our environment at both a global and local level.” —Ferns and Feathers “The steps to take toward making your garden part of the Homegrown National Park.”—Horticulture

“Tallamy is one of the most original and persuasive present-day authors on conservation.” B>Edward O. Wilson, University Research Professor Emeritus, Harvard University

“Doug Tallamy is a quiet revolutionary and a hero of our time, taking back the future one yard at a time. In Nature’s Best Hope, he shows how each of us can help turn our cities, towns and world into engines of biodiversity and human health.”B>Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods and Our Wild Calling

“Here is one area where individual action really can help make up for all that government fails to do: your backyard can provide the margin to keep species alive. Mow less, think more!”B>Bill McKibben, author of Falter

“Tallamy is a key contributor to the explosive leap in public understanding of the impact of humans on the natural world and how we can repair the damage we cause.”B>Grandy Drummer

“Tallamy shows how to transform yards into ecological wonderlands full of vibrant life. Your local birds, butterflies, and plants will thank you for learning from his wise advice.”B>David George Haskell, author of The Forest Unseen, Pulitzer finalist, and The Songs of Trees

“This is a handbook for not only transforming your own yard, but for talking to your neighbors, the teachers in the paved schoolyard next door, and your town councilors about connecting one green haven to another to build wildlife corridors that become, as Tallamy puts it, a Homegrown National Park.”B>Anne Raver, award-winning columnist and author of Deep in the Green

“A clarion call to go native: acting locally in your yard or neighborhood and thinking globally about the biodiversity crisis.”B>Scott Freeman, author of Saving Tarboo Creek

“Doug Tallamy’s inspiring vision of a human landscape capable of supporting a wondrous diversity of life is powerfully articulated in Nature’s Best Hope.”B>Rick Darke, landscape designer, lecturer, photographer, and coauthor of Gardens of the High Line

“A revelatory guide whose application can begin just outside our doors.” I>Booklist

“Tallamy provides answers in a down-to-earth, personalized style…this is an essential addition to most gardening collections.” I>Library Journal

“Nature’s Best Hope advocates not just a horticultural revolution, but a cultural one, bridging the human-dominated landscape and the natural world.” /B>Smithsonian Magazine

“An inspiring and necessary book…Tallamy is so important in today’s ecological efforts…everyone can (and should) read his writings.” B>The Garden Club of America

“An outstanding book, full of deep insights, and practical advice.” —Dennis Liu, Ph.D., Vice President for Education, EO Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

“A full-blown manifesto that calls for the radical rethinking of the American residential landscape, starting with the lawn.” B>The Washington Post

“If you’d like to turn your own little postage stamp of native soil into a conservation effort, Nature’s Best Hope, is a great place to begin.” I>New York Times

“Nature’s Best Hope isn’t just what we can do with boots on the ground; it’s about fighting for a changed cultural mindset. We can experience the health, wellness, and resiliency of life if we’re willing to embrace all of the messy complications that make this world worth experiencing in all its wild promise.” I>The American Gardener

“In a world full of doom and gloom, Dr. Tallamy's latest book is an uplifting and empowering guide to how each and every one of us can be part of the conservation movement and it all starts with native plants.” B>In Defense of Plants

“To support conservation efforts, you need look no farther than your own backyard… Nature’s Best Hope offers practical tips for creating habitat that protects and nurtures nature.” —National Geographic

“Even a single person acting boldly with [Tallamy’s] goal in mind could be a crucial source of inspiration for others around them.” —Associated Press

“If you’re concerned about doing something good for the environment, Nature’s Best Hope is the blueprint you need. By acting now, you can help preserve our precious wildlife—and the planet—for future generations.” B>Hockessin Community News

“Nature’s Best Hope helps us to understand the urgency we all should and must have as we try to make a difference to our ever-changing planet.” B>Nature Revisited

“An essential read for those concerned with the fate of planet Earth and its creatures.” B>Connecticut Gardener

“Nature’s Best Hope is a message for every land owner, renter, property manager, container gardener, government planner and administrator: You have a vital role to play in the survival of biodiversity on this planet!” B>The Press of Atlantic City

“Here’s a read that does something critically important. It restores hope by giving us normal mortals something we can do.” B>Smokey Mountain News

“Nature's best hope—is all of us.” B>Yakima Herald

“Become part of Tallamy’s army of gardeners converting yards and wasted spaces of America into Homegrown National Park.” —Wyoming Tribune Eagle

“An important book about the urgent importance of planting natives…eye-opening and transformative.” B>The Sun-Sentinel

“A new and inspiring vision of what could be achieved if concerned individuals join together to transform the common attitudes and practices that have shaped our own backyards.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use