By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

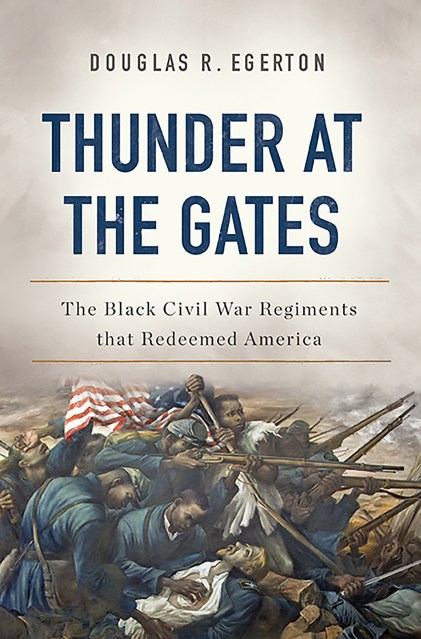

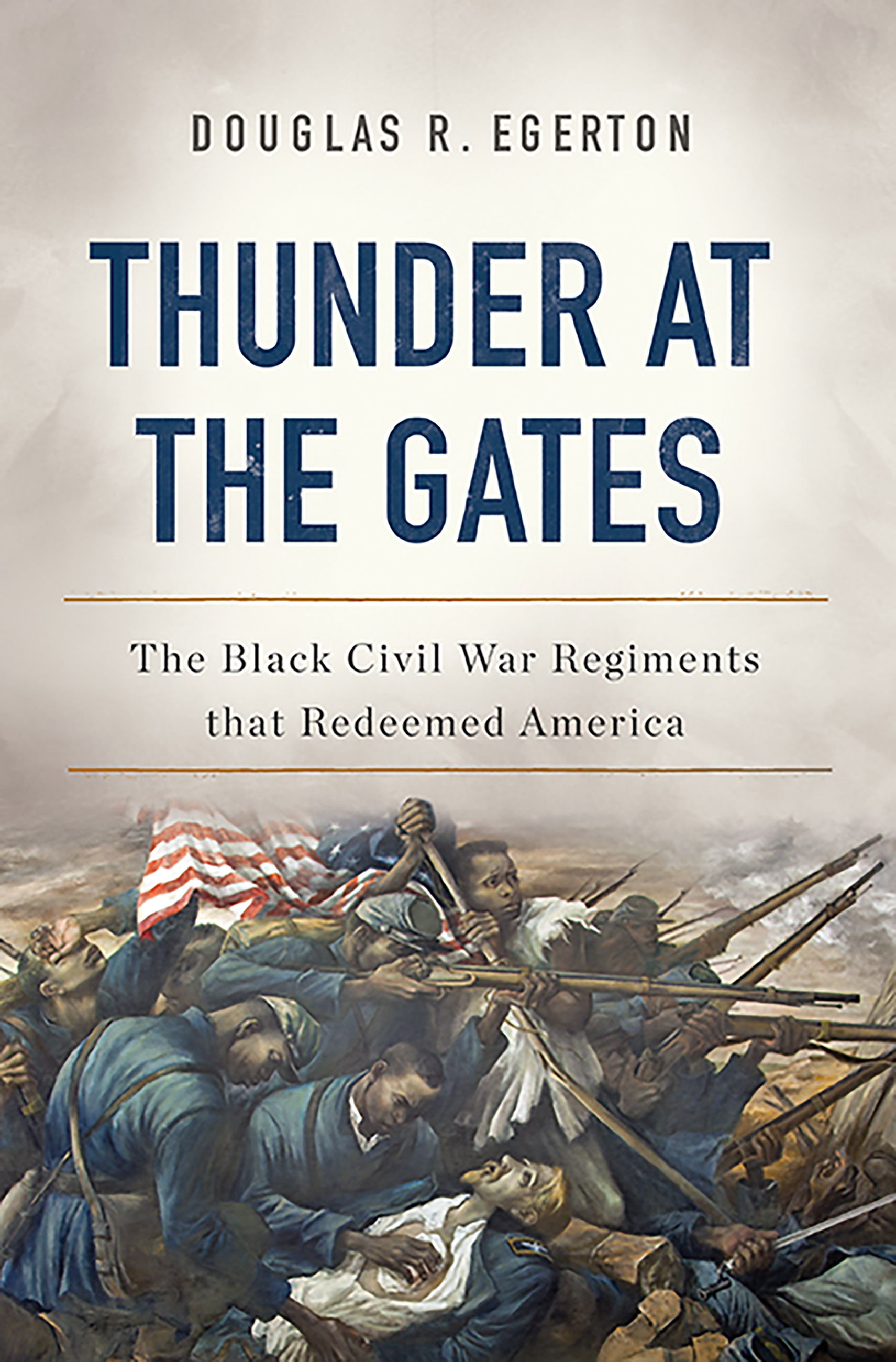

Thunder at the Gates

The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2016

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096657

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Soon after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, abolitionists began to call for the creation of black regiments. At first, the South and most of the North responded with outrage-southerners promised to execute any black soldiers captured in battle, while many northerners claimed that blacks lacked the necessary courage. Meanwhile, Massachusetts, long the center of abolitionist fervor, launched one of the greatest experiments in American history.

In Thunder at the Gates, Douglas Egerton chronicles the formation and battlefield triumphs of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry and the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry-regiments led by whites but composed of black men born free or into slavery. He argues that the most important battles of all were won on the field of public opinion, for in fighting with distinction the regiments realized the long-derided idea of full and equal citizenship for blacks.

A stirring evocation of this transformative episode, Thunder at the Gates offers a riveting new perspective on the Civil War and its legacy.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use