Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

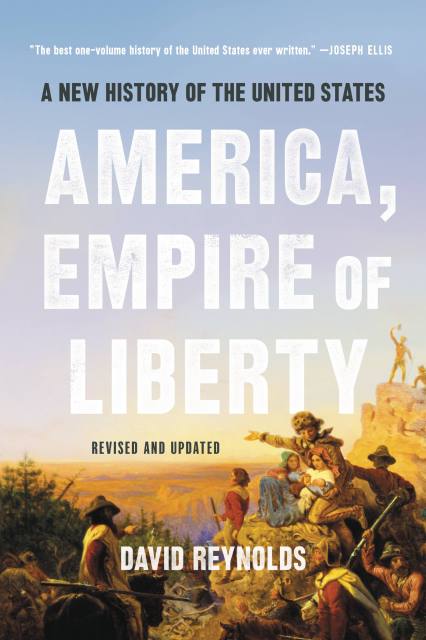

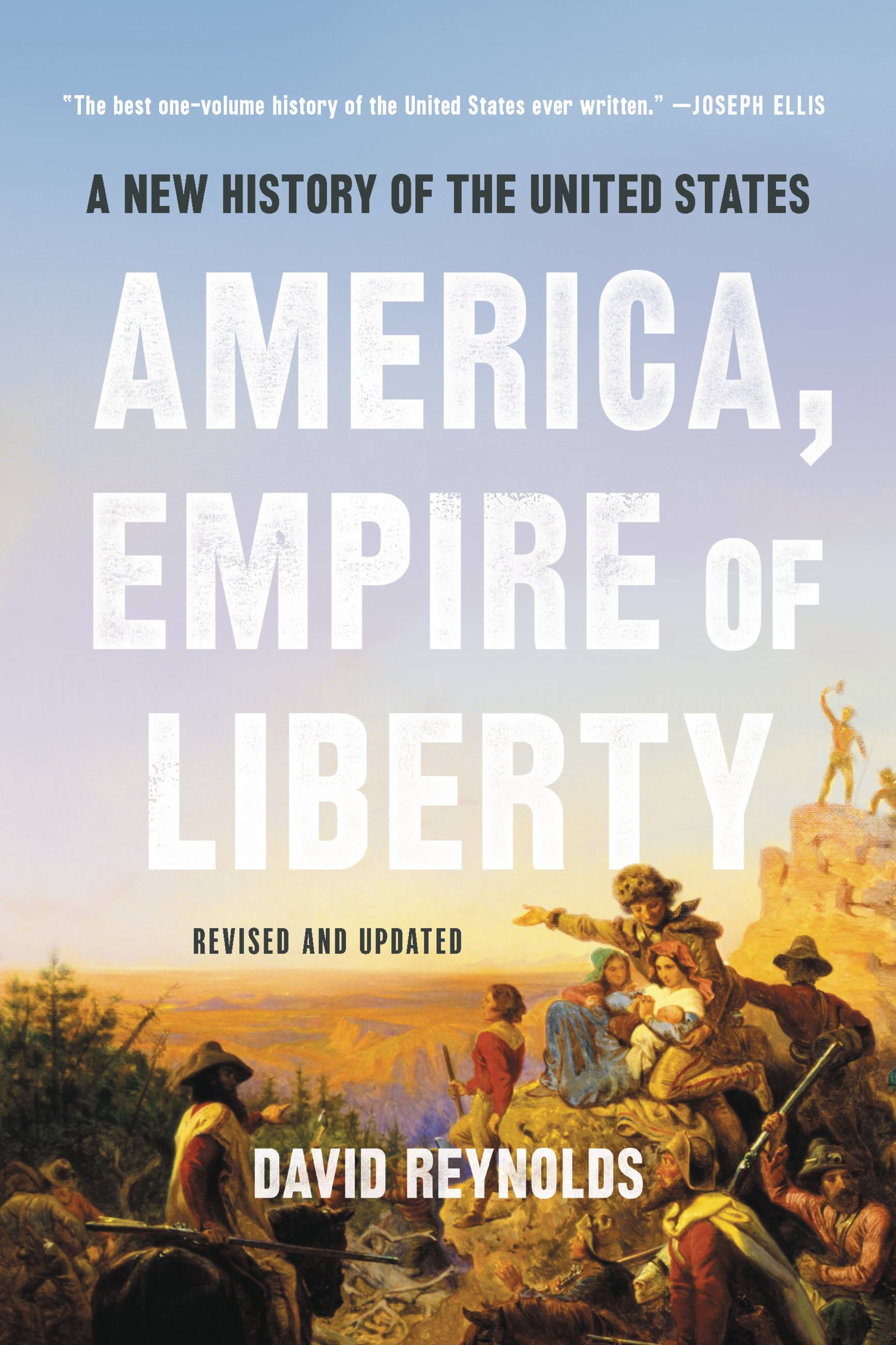

America, Empire of Liberty

A New History of the United States

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 25, 2021

- Page Count

- 640 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541675698

Price

$22.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 25, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“The best one-volume history of the United States ever written” (Joseph J. Ellis), now updated to cover the Obama and Trump presidencies

In America, Empire of Liberty, prizewinning historian David Reynolds offers a single-volume account spanning the entire course of US history, from 1776 to today. He demonstrates how tensions between empire and liberty have often been resolved by faith. Both evangelical Protestantism and the larger belief in the nation’s righteousness, he explains, have energized American politics for centuries and driven the country’s expansion.

In this new edition, Reynolds also addresses America’s turbulent recent history. From the 2008 financial crash to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, he recounts the dramas of change and crisis at home and abroad during the Obama and Trump presidencies, as well as ongoing cultural conflicts over race and identity. In an uncertain era, America, Empire of Liberty offers essential insight into our nation’s past.

-

"In an animated overview up to the present time, Cambridge historian Reynolds (In Command of History) captures the sprawling chronicle of a nation forged from the fires of revolution, populated by immigrants and constantly evolving politically and culturally... Most readers will find Reynolds's epic overview provocative and enjoyable."Publishers Weekly

-

"Dazzlingly sweeping yet stippled with detail, this one-volume narrative runs from 1776 to Obama's election, serving up fresh insights along the way."American History Magazine

-

"Concise and still-inclusive...teeming...an evenhanded distillation of America's story from a singular outside observer."Kirkus

-

"Let us not mince words...this is the best one-volume history of the United States ever written...At least on the face of it, no single mind can master this mountain of material, avoid the almost-inevitable factual blunders, negotiate the long-standing scholarly controversies, and control the narrative in clear and at-times-lyrical prose. But that is precisely what Reynolds has done...[A] remarkable tour of the American past."The National Interest