Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

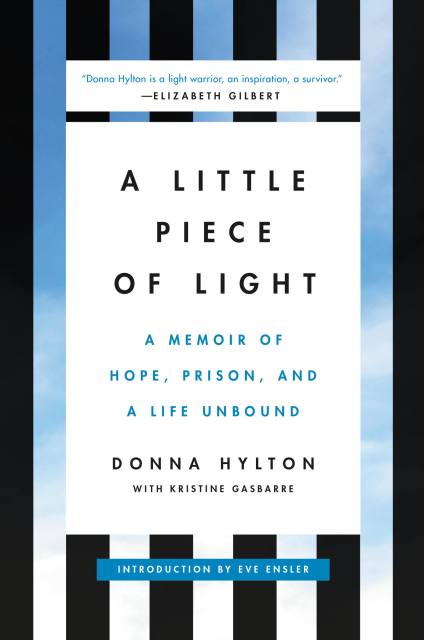

A Little Piece of Light

A Memoir of Hope, Prison, and a Life Unbound

Contributors

By Donna Hylton

With Kristine Gasbarre

Foreword by Eve Ensler

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 5, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Like so many women before her and so many women yet to come, Donna Hylton’s early life was a nightmare of abuse that left her feeling alone and convinced of her worthlessness. In 1986, she took part in a horrific act and was sentenced to 25 years to life for kidnapping and second-degree murder. It seemed that Donna had reached the end–at age 19, due to her own mistakes and bad choices, her life was over.

A Little Piece of Light tells the heartfelt, often harrowing tale of Donna’s journey back to life as she faced the truth about the crime that locked her away for 27 years…and celebrated the family she found inside prison that ultimately saved her. Behind the bars of Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, alongside this generation’s most infamous criminals, Donna learned to fight, then thrive. For the first time in her life, she realized she was not alone in the abuse and misogyny she experienced–and she was also not alone in fighting back.

Since her release in 2012, Donna has emerged as a leading advocate for criminal justice reform and women’s rights who speaks to politicians, violent abusers, prison officials, victims, and students to tell her story. But it’s not her story alone, she is quick to say. She also represents the stories of thousands of women who have been unable to speak for themselves, until now.

Genre:

-

"The treatment of each unique child is the true measure of the state of the world. Donna Hylton was punished for being born female, black, and brilliant--yet she survived to create her own life. A Little Piece of Light will tell you just how fragile--and how indestructible--the human spirit can be."Gloria Steinem

-

"Donna Hylton's painful yet liberating memoir will certainly be transformative for many who read her words. As a survivor of sexual abuse and violence--inside and outside prison--she tells the whole truth of her experience, including her deep regret for the moments that she's harmed others and her passionate commitment to co-creating a justice system that acknowledges the little piece of light that shines within us no matter who we are, what we've done, or what has been done to us."Michelle Alexander, New York Times bestselling author of The New Jim Crow

-

"Donna Hylton is a light warrior, an inspiration, a survivor, a profound storyteller, and an important teacher for our times."Elizabeth Gilbert, New York Times bestselling author of Eat, Pray, Love and Big Magic

-

"[Donna Hylton's] life stands as a case study illustrating how prison reform efforts and support for women in abusive situations can transform individual lives and society.... Since her release, Hylton has continued her fight for women who have no voice. Her story stands as a harrowing, yet powerful, picture of what's possible when women escape brutality and encounter hope, even in the most unlikely of places."Associated Press

-

"Donna has a remarkable capacity for turning pain into power. She's focused, determined, present, thoughtful, passionate, and tireless. She's an invaluable asset to us all."Rosario Dawson,actress, writer, singer, and activist

-

"Donna Hylton's A Little Piece of Light reveals her life journey in an exquisitely written memoir. Donna suffered so long before finding a place to belong. It brings into question how America criminalizes the trauma of poor women. This book is a real page-turner that has you sitting on the edge of your seat.... A must read."Susan Burton, author of Becoming Ms. Burton: From Prison to Recovery to Leading the Fight Against Incarcerated Women

-

"I first met Donna Hylton at Riverside Church when she had just been released from prison after serving 27 years, and she is an unforgettable presence. In this riveting book Donna bravely and honestly does the difficult work of reconciling the harm she suffered and the harm she caused, and the reasons both are important. A Little Piece of Light is a gripping account of promises kept or broken, showing the incredible resilience and triumph of women in the face of neglect and violence. Donna Hylton's story is both wrenching and life-affirming, and essential reading to anyone who cares about women, safety and justice."Piper Kerman, author of Orange Is the New Black

-

"Donna Hylton proves it's not where you start but where you finish. In her searing narrative, A Little Piece of Light, she recounts spending more than 25 years at New York's Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for kidnapping and second-degree murder. How she got there will rock you to your core."Essence

-

"Intimate and disturbing, the book reveals the ways women are silenced and victimized in society, and it also tells the inspiring story of how one woman survived a prison nightmare to go on to help other incarcerated women 'speak out about the violence in their lives.' A wrenching memoir of overcoming seemingly insurmountable abuse and finding fulfillment."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Gripping.... [A Little Piece of Light] is a meditation on redemption and learning to love and forgive."Booklist

-

"I have witnessed Donna struggle with her difficult past, make tremendous gains in confronting and reconciling with her childhood abuse, take personal responsibility for her past actions, have deep remorse for the consequences of those actions, and commit herself to improving the lives of those around her."Sister Mary Nerney,psychologist and founding director of STEPS to End Family Violence

-

"In her emotionally startling memoir, criminal justice reform activist Donna Hylton takes readers from humanity's dark evils to its shining inspirations.... A Little Piece of Light is a big reminder of how people share much more in common than not. Even more importantly, it's a beacon capable of leading others out of the darkness that Hylton endured."Shelf Awareness

- On Sale

- Jun 5, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316559218

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use