By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

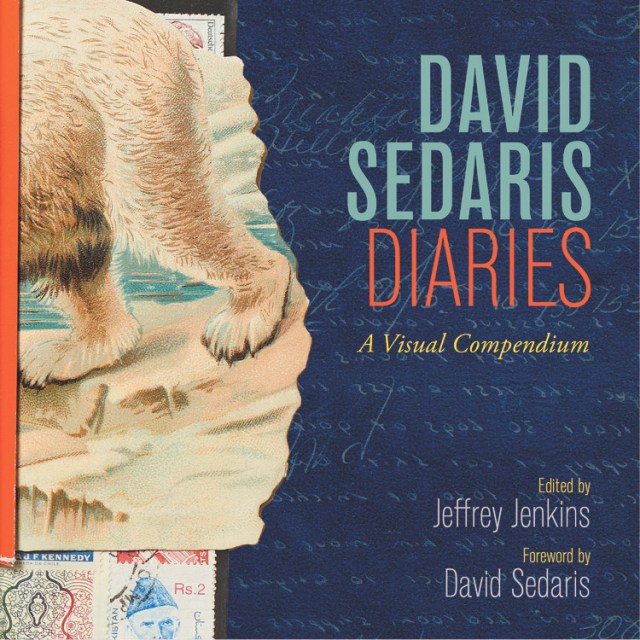

David Sedaris Diaries

A Visual Compendium

Contributors

Foreword by David Sedaris

Edited by Jeffrey Jenkins

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316431712

Price

$50.00Price

$60.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $50.00 $60.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A remarkable illustrated volume of artwork and images selected from the diaries David Sedaris has been creating for four decades

In this richly illustrated book, readers will for the first time experience the diaries David Sedaris has kept for nearly 40 years in the elaborate, three-dimensional, collaged style of the originals. A celebration of the unexpected in the everyday, the beautiful and the grotesque, this visual compendium offers unique insight into the author’s view of the world and stands as a striking and collectible volume in itself.

Compiled and edited by Sedaris’s longtime friend Jeffrey Jenkins, and including interactive components, postcards, and never-before-seen photos and artwork, this is a necessary addition to any Sedaris collection, and will enthrall the author’s fans for many years to come.

In this richly illustrated book, readers will for the first time experience the diaries David Sedaris has kept for nearly 40 years in the elaborate, three-dimensional, collaged style of the originals. A celebration of the unexpected in the everyday, the beautiful and the grotesque, this visual compendium offers unique insight into the author’s view of the world and stands as a striking and collectible volume in itself.

Compiled and edited by Sedaris’s longtime friend Jeffrey Jenkins, and including interactive components, postcards, and never-before-seen photos and artwork, this is a necessary addition to any Sedaris collection, and will enthrall the author’s fans for many years to come.

Genre:

-

"Fans of Sedaris's acerbic wit will want to check out this stunning new diary compilation...the writer's worldview comes to gorgeous, bitingly funny life."Entertainment Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use