Promotion

25% off sitewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery! Code BEST25 automatically applied at checkout!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

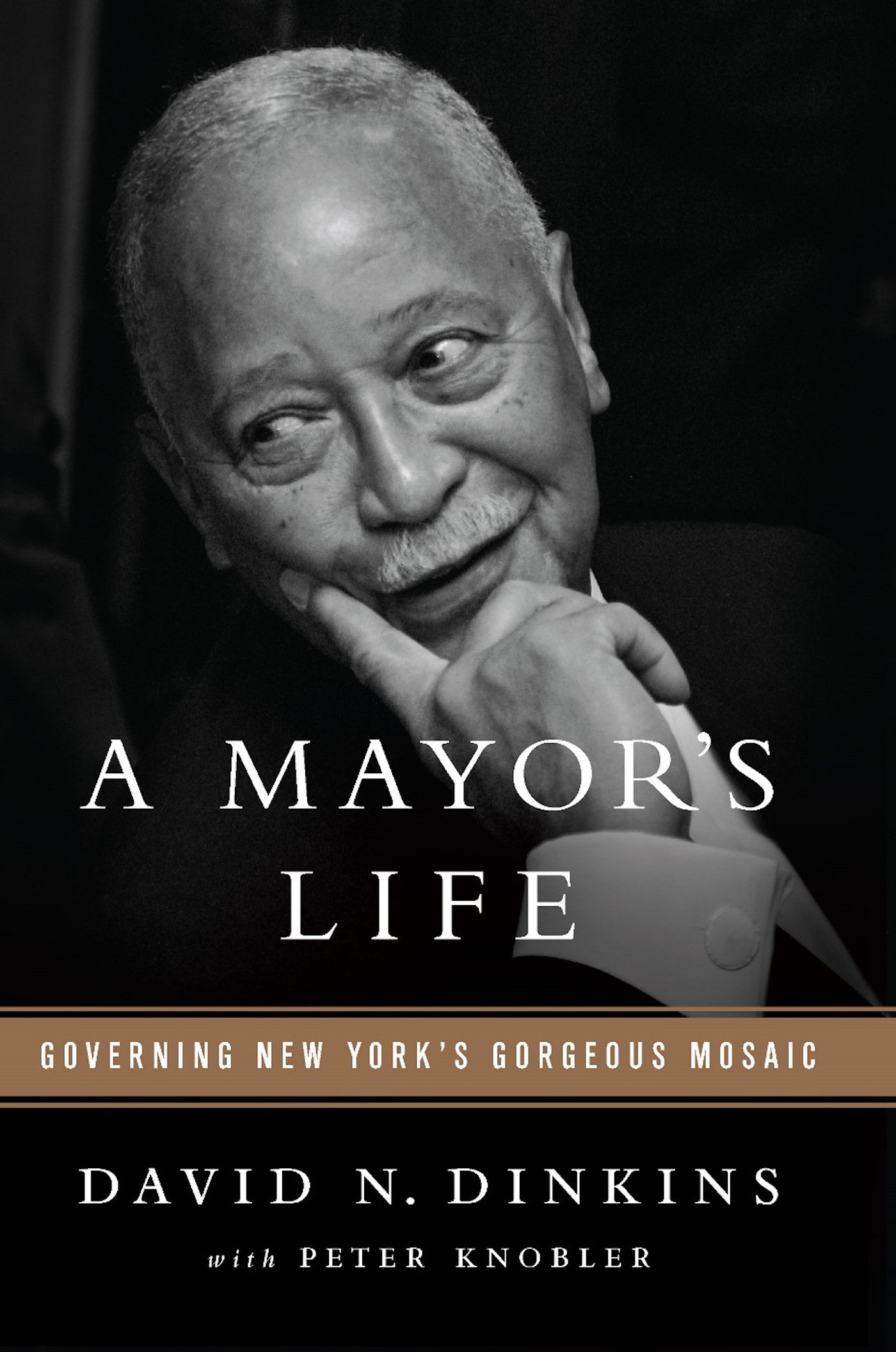

A Mayor’s Life

Governing New York's Gorgeous Mosaic

Contributors

With Peter Knobler

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 408 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393027

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.99 $34.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The political career of David Dinkins is set against the backdrop of the rising influence of a broader demographic in New York politics, including far greater segments of the city’s “gorgeous mosaic.” After a brief stint as a New York assemblyman, Dinkins was nominated as a deputy mayor by Abe Beame in 1973, but ultimately declined because he had not filed his income tax returns on time. Down but not out, he pursued his dedication to public service, first by serving as city clerk. In 1986, Dinkins was elected Manhattan borough president, and in 1989, he defeated Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani to become mayor of New York City, the largest American city to elect an African American mayor.

As the newly-elected mayor of a city in which crime had risen precipitously in the years prior to his taking office, Dinkins vowed to attack the problems and not the victims. Despite facing a budget deficit, he hired thousands of police officers, more than any other mayoral administration in the twentieth century, and launched the “Safe Streets, Safe City” program, which fundamentally changed how police fought crime. For the first time in decades, crime rates began to fall — a trend that continues to this day. Among his other major successes, Mayor Dinkins brokered a deal that kept the US Open Tennis Championships in New York — bringing hundreds of millions of dollars to the city annually — and launched the revitalization of Times Square after decades of decay, all the while deflecting criticism and some outright racism with a seemingly unflappable demeanor. Criticized by some for his handling of the Crown Heights riots in 1991, Dinkins describes in these pages a very different version of events.

A Mayor’s Life is a revealing look at a devoted public servant and a New Yorker in love with his city, who led that city during tumultuous times.

-

Sam Roberts, New York Times Book Review

“An inspiring account of New York's first black mayor and the hopes he inherited, many of them dashed on the shoals of fiscal reality and a sometimes hapless search for consensus.”

Booklist

“Dinkins trumpets his accomplishments as mayor and offers some insights into the boisterous New York political scene, the rise of Harlem's political influence, and the evolution of black political leaders during a turbulent period.”

Kirkus Reviews

"A former New York City mayor recounts his personal journey from humble roots to running America's most iconic metropolis…A frank, unique look at the many challenges in New York City politics."

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use