By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

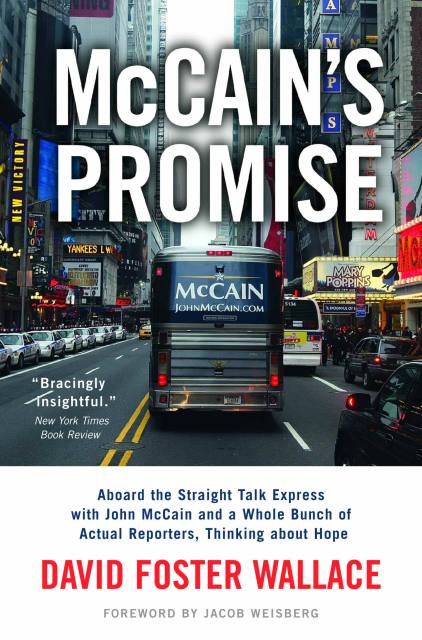

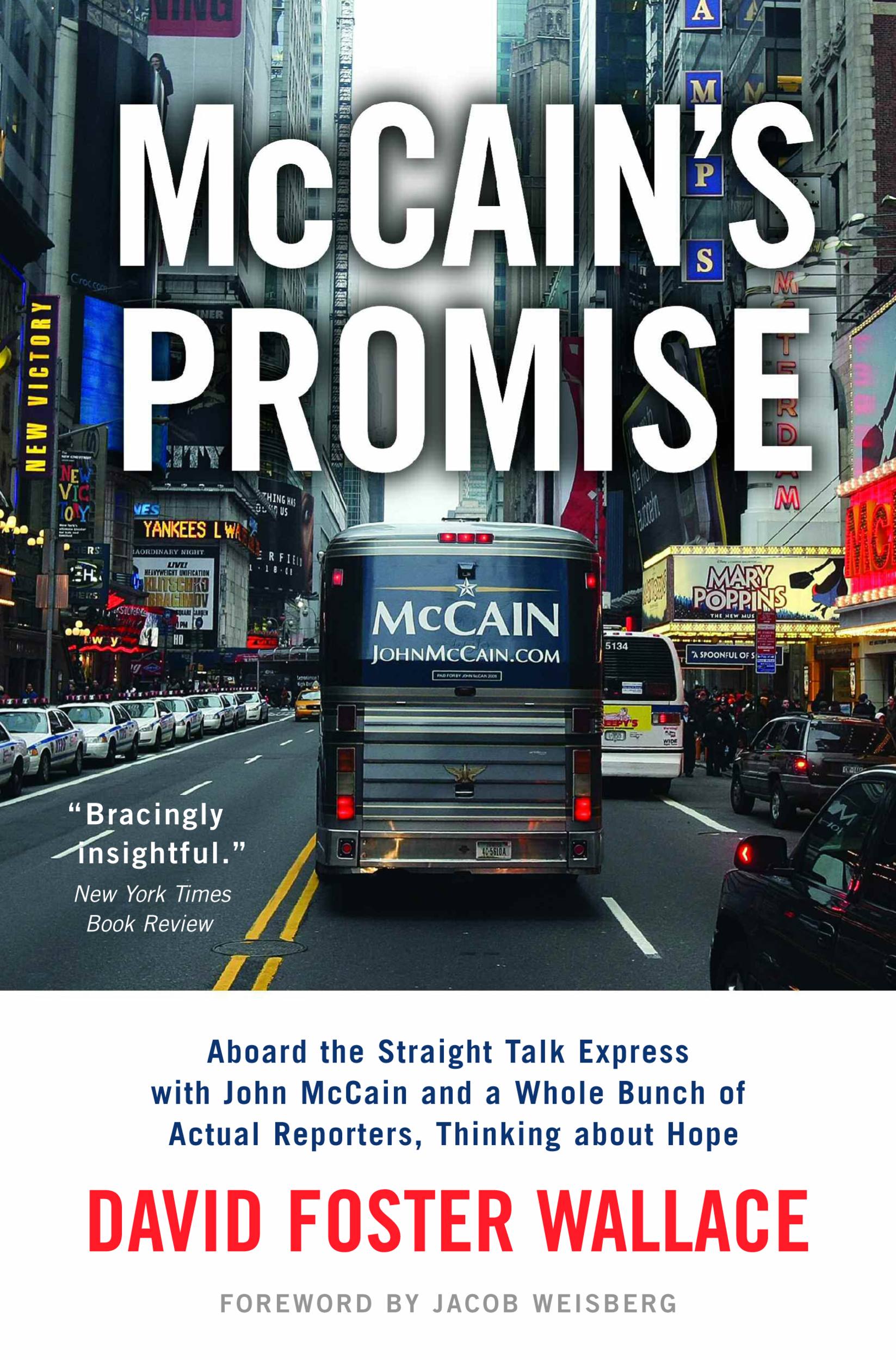

McCain’s Promise

Aboard the Straight Talk Express with John McCain and a Whole Bunch of Actual Reporters, Thinking About Hope

Contributors

Foreword by Jacob Weisberg

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2008

- Page Count

- 144 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316040945

Price

$5.99Price

$7.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

That’s the question David Foster Wallace set out to explore when he first climbed aboard Senator McCain’s campaign caravan in February 2000. It was a moment when Mccain was increasingly perceived as a harbinger of change, the anticandidate whose goal was “to inspire young Americans to devote themselves to causes greater than their own self-interest.” And many young Americans were beginning to take notice.

To get at “something riveting and unspinnable and true” about John Mccain, Wallace finds he must pierce the smoke screen of spin doctors and media manipulators. And he succeeds-in a characteristically potent blast of journalistic brio that not only captures the lunatic rough-and-tumble of a presidential campaign but also delivers a compelling inquiry into John McCain himself: the senator, the POW, the campaign finance reformer, the candidate, the man.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use