Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

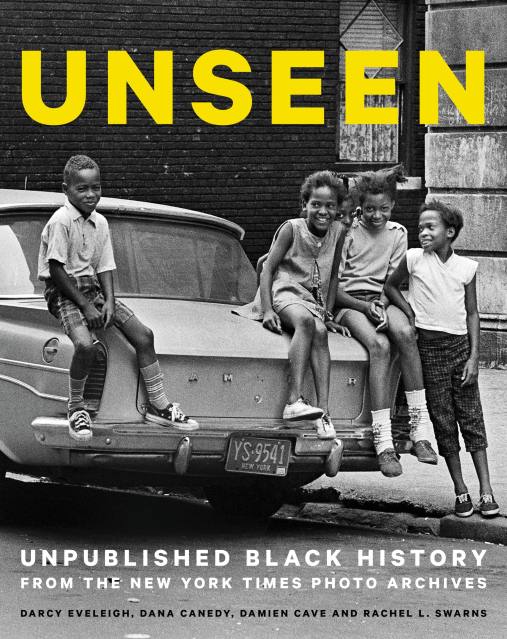

Unseen

Unpublished Black History from the New York Times Photo Archives

Contributors

By Dana Canedy

By Darcy Eveleigh

By Damien Cave

By Rachel L. Swarns

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.99 $37.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 17, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

New York Times photo editor Darcy Eveleigh made an unwitting discovery when she found dozens of never-before-published photographs from Black history in the crowded bins of the Times archives in 2016. She and three colleagues, Dana Canedy, Damien Cave, and Rachel L. Swarns, began exploring the often untold stories behind the images and chronicling them in a series entitled “Unpublished Black History” that was later published by the newspaper.

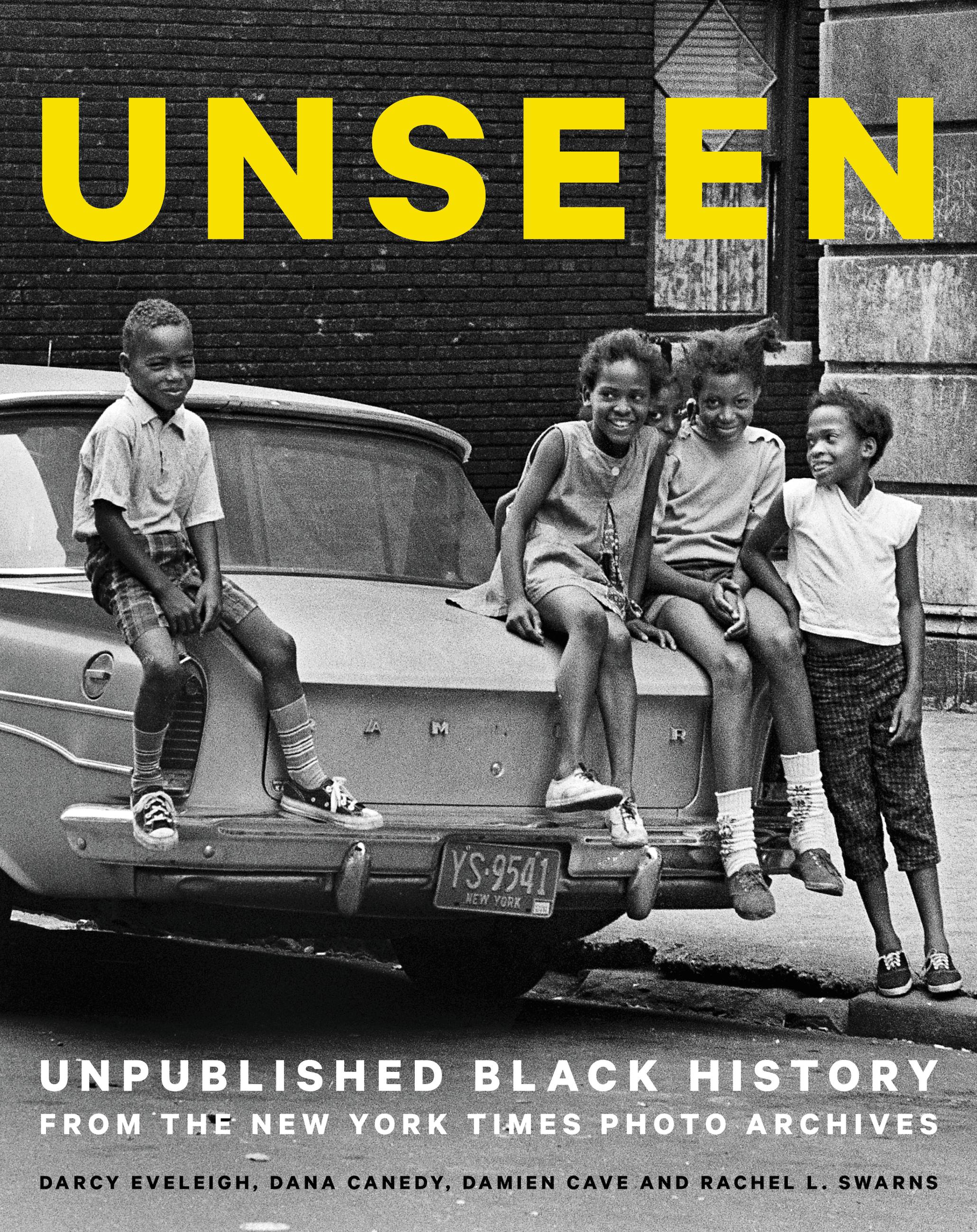

Unseen showcases those photographs and digs even deeper into the Times’s archives to include 175 photographs and the stories behind them in this extraordinary collection. Among the entries is a 27-year-old Jesse Jackson leading an anti-discrimination rally in Chicago; Rosa Parks arriving at a Montgomery courthouse in Alabama; a candid shot of Aretha Franklin backstage at the Apollo Theater; Ralph Ellison on the streets of his Manhattan neighborhood; the firebombed home of Malcolm X; and a series by Don Hogan Charles, the first black photographer hired by the Times, capturing life in Harlem in the 1960s.

Why were these striking photographs not published? Did the images not arrive in time to make the deadline? Were they pushed aside by the biases of editors, whether intentional or unintentional? Unseen dives deep into the Times’s archives to showcase this rare collection of photographs and stories for the very first time.

Genre:

-

"Maya Angelou said that 'there is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you. Indeed, there is an agony in our nation that the stories, the voices, and the images of Black Americans are so unknown, untold, and unseen in our wider understanding of history. This bountiful collection of once-unpublished photographs both gives expressive voice to their subjects and helps to relieve this agony, bringing to life a more complete picture of the compelling, complex, and beautiful story that is America."Cory Booker, U.S. senator and bestselling author of United: Thoughts on Finding Common Ground and Advancing the Common Good.

-

"Unseen reminds me of a lost black history version of 'You Are There,' told through photographs that The Times commissioned but chose not to print. This book is a vivid account of race relations in America, narrated through images that survived between the spaces of stories, in the gaps, silences, and lacuna buried in the paper's archives. They constitute a remarkably vivid parallel text to the last half century of American history, creating an extraordinarily moving visual narrative of the feelings and actions of black Americans in the striking particularity of black-and-white photography. The book simulates what it would have been like to read The Times each day for the last half century, if the full picture of the African American experience had made the cut. If any book proves that it is never too late to publish 'all the news'--and images--'fit to print,' this is it.Henry Louis Gates, Jr., director of Harvard's Hutchins Center for African American Research and an Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker

-

"By unearthing these fascinating photographs and sharing the stories behind them, the contributors to this extraordinary project have created a treasure."Marian Wright Edelman, president, Children's Defense Fund

-

"This book brings the excitement of opening a time capsule, with powerful photographs and searching commentary by an all-star cast that gives us new and original insights into modern African American history."Michael Beschloss, historian and bestselling author of Presidential Courage: Brave Leaders and How They Changed America 1789-1989

-

"The power of images is undeniable; so, for many years, has been the power of the TheNew York Times. This new volume, by a team headed by a Times photo editor, contains 175 remarkable (and hitherto-unpublished) photos of significant moments in African-American life and culture."St. Louis Post-Dispatch

- On Sale

- Oct 17, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316552974

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use