Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

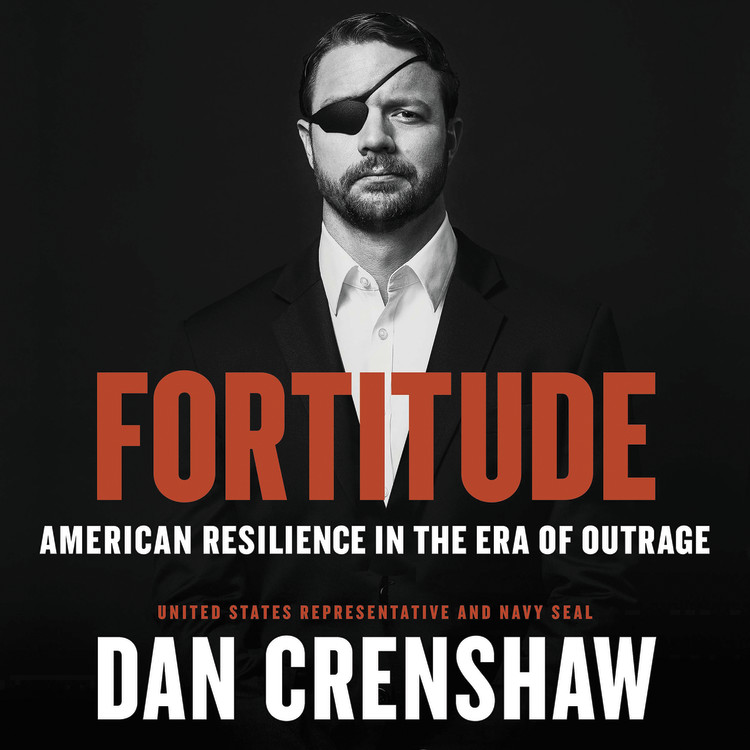

Fortitude

American Resilience in the Era of Outrage

Contributors

By Dan Crenshaw

Read by Dan Crenshaw

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 7, 2020

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549151187

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jordan Peterson's Twelve Rules for Life meets Jocko Willink and Leif Babin's Extreme Ownership in this tough-love leadership book from a Navy SEAL and rising star in Republican politics.

In 2012, on his third tour of duty, an improvised explosive device left Dan Crenshaw's right eye destroyed and his left blinded. Only through the careful hand of his surgeons, and what doctors called a miracle, did Crenshaw's left eye recover partial vision. And yet, he persevered, completing two more deployments. Why? There are certain stories we tell ourselves about the hardships we face—we can become paralyzed by adversity or we can adapt and overcome. We can be fragile or we can find our fortitude. Crenshaw delivers a set of lessons to help you do just that.

Most people's everyday challenges aren't as extreme as surviving combat, and yet our society is more fragile than ever: exploding with outrage, drowning in microaggressions, and devolving into divisive mob politics. The American spirit—long characterized by grit and fortitude—is unraveling. We must fix it.

That's exactly what Crenshaw accomplishes with Fortitude. This book isn't about the problem, it's about the solution. And that solution begins with each and every one of us. We must all lighten up, toughen up, and begin treating our fellow Americans with respect and grace.

Fortitude is a no-nonsense advice book for finding the strength to deal with everything from menial daily frustrations to truly difficult challenges. More than that, it is a roadmap for a more resilient American culture. With meditations on perseverance, failure, and finding much-needed heroes, the book is the antidote for a prevailing "safety culture" of trigger warnings and safe spaces. Interspersed with lessons from history and psychology is Crenshaw's own story of how an average American kid from the Houston suburbs went from war zones to the halls of Congress—and managed to navigate his path with a sense of humor and an even greater sense that, no matter what anyone else around us says or does, we are in control of our own destiny.

In 2012, on his third tour of duty, an improvised explosive device left Dan Crenshaw's right eye destroyed and his left blinded. Only through the careful hand of his surgeons, and what doctors called a miracle, did Crenshaw's left eye recover partial vision. And yet, he persevered, completing two more deployments. Why? There are certain stories we tell ourselves about the hardships we face—we can become paralyzed by adversity or we can adapt and overcome. We can be fragile or we can find our fortitude. Crenshaw delivers a set of lessons to help you do just that.

Most people's everyday challenges aren't as extreme as surviving combat, and yet our society is more fragile than ever: exploding with outrage, drowning in microaggressions, and devolving into divisive mob politics. The American spirit—long characterized by grit and fortitude—is unraveling. We must fix it.

That's exactly what Crenshaw accomplishes with Fortitude. This book isn't about the problem, it's about the solution. And that solution begins with each and every one of us. We must all lighten up, toughen up, and begin treating our fellow Americans with respect and grace.

Fortitude is a no-nonsense advice book for finding the strength to deal with everything from menial daily frustrations to truly difficult challenges. More than that, it is a roadmap for a more resilient American culture. With meditations on perseverance, failure, and finding much-needed heroes, the book is the antidote for a prevailing "safety culture" of trigger warnings and safe spaces. Interspersed with lessons from history and psychology is Crenshaw's own story of how an average American kid from the Houston suburbs went from war zones to the halls of Congress—and managed to navigate his path with a sense of humor and an even greater sense that, no matter what anyone else around us says or does, we are in control of our own destiny.

-

"This solution-oriented book is a must-read for anyone who loves America and believes that the grit and determination that founded her are in need of a revival. FORTITUDE is a set of tools for being tougher, yes, but it is also a guide for preserving the freedoms and foundations of our great country. Dan's experiences as a SEAL and now Congressman give FORTITUDE instant credibility, with a message that desperately needs to be heard far and wide."Marcus Luttrell, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Lone Survivor

-

"As someone who has served our country on the front lines in Afghanistan, Dan Crenshaw knows what it means to separate the trivial from the truly meaningful. In FORTITUDE, he brings this vital experience to bear, offering keen insights on how to unite our fractured country and take pride in its founding ideals -- even as we face up to the tough truths of its history."Condoleezza Rice, New York Times bestselling author of Democracy: Stories from the Long Road to Freedom

-

"The American experiment is about mental toughness in the face of adversity -- because freedom takes toughness. I know no one tougher than Dan Crenshaw, which is probably why his new book, FORTITUDE, is a must-read. Dan combines real-world experience with a command of America's philosophical roots, and he reminds us that what made America great still beats in the breasts of those who continue to fight for a culture of liberty."Ben Shapiro, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Right Side of History: How Reason and Moral Purpose Made the West Great

-

"Life is a struggle; it is a demanding test, not only for us as individuals, but also for us as a nation. FORTITUDE distills and consolidates crucial elements from ancient philosophy, modern psychology, the SEAL ethos, and Dan Crenshaw's personal experiences as a leader and warrior into a clear and pragmatic guide for any person who wants to confront the challenges of life with courage, tenacity, and fortitude. By living the principles set forth in this book, any person can make their world -- and thereby our world -- a better place."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: center; font: 12.0px Arial}Jocko Willink, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Extreme Ownership

-

"A must-read! Dan Crenshaw has crafted a truly inspiring narrative that grippingly details the life of a hero, replete with grit, courage, and a refusal to let the darkest of circumstances stop him from serving his country at the highest levels. This is not just the story of a hero; it is an informed recipe for success in life, containing a useful blueprint for bringing out our best, most resilient heroic self within each of us."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: center; font: 12.0px Arial}Professor Scott T. Allison, University of Richmond, author of Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them

-

"FORTITUDE is a much-needed reminder that the American Dream is alive and well, as long as we are willing to work for it. Through stories of personal responsibility and perseverance --with humor along the way -- it gives young people the advice they need to be successful. And it gives them the courage to rise above the mob and today's political divisions. Dan reminds us exactly why we are so blessed to live in America."Nikki Haley, Former UN Ambassador & New York Times bestselling author of With All Due Respect: Defending America with Grit and Grace

-

"A wide exploration of prevailing cultural maladies that flow from the decline of resilience...[FORTITUDE] has elements of a combat memoir, social critique, political analysis and self-improvement manual. These disparate genres are seamlessly woven into a plain-spoken, cohesive and timely argument and call for renewal."Wall Street Journal