Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

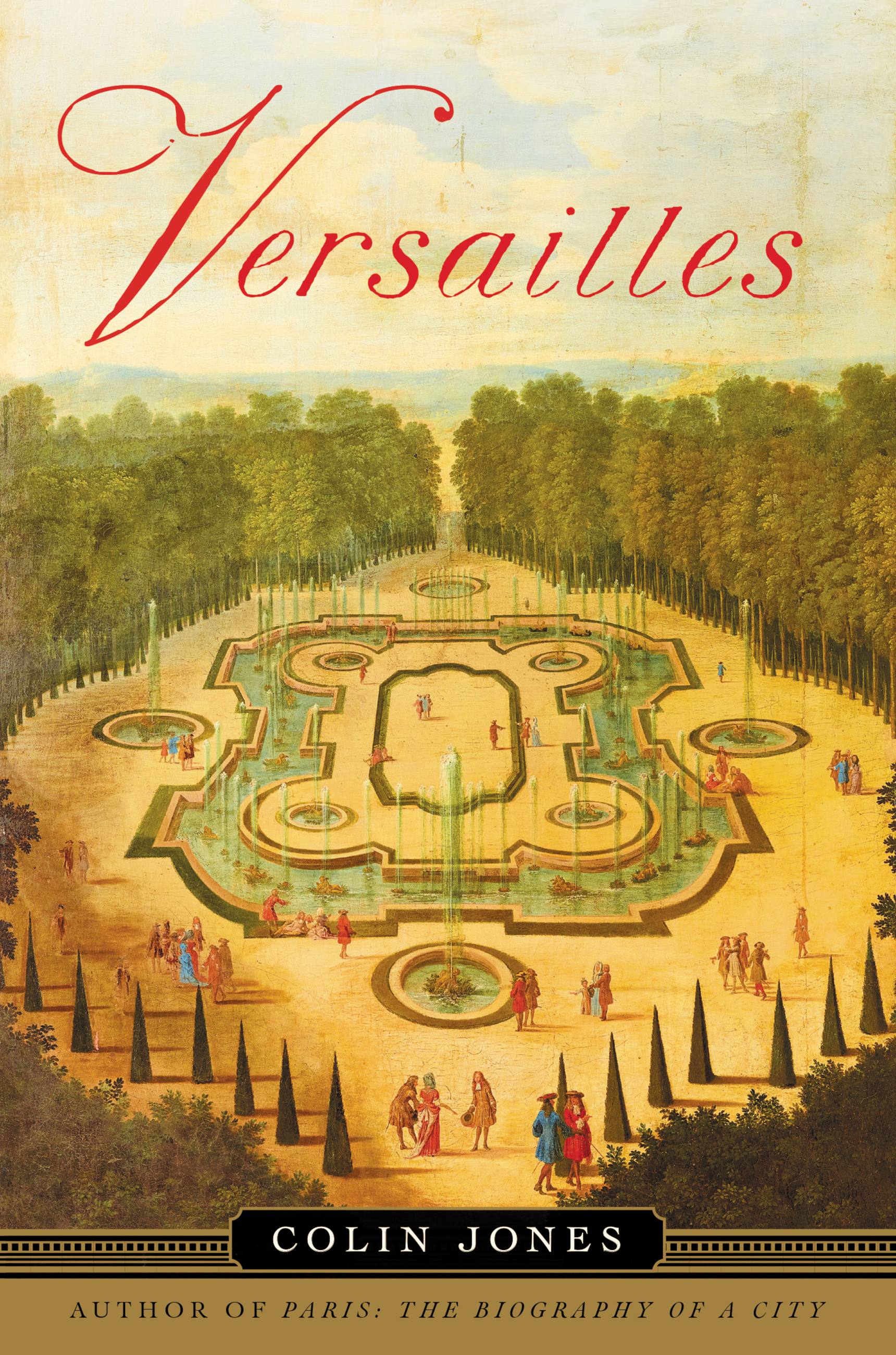

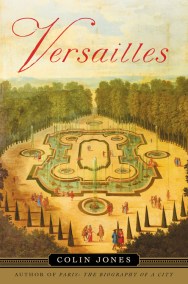

Versailles

Contributors

By Colin Jones

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541673458

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.00 $32.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Nothing represents the glorious and fraught history of France quite like the Palace of Versailles. Made famous by the absolutist king Louis XIV, Versailles became legendary for the splendor of its revels — but then, after the Revolution of 1789, it fell into disrepute as a reminder of royal excess and abuse of power. Subsequent French governments struggled with how to handle the opulent palace and grounds — should the site be memorialized, trivialized, rehabilitated, or even destroyed outright?

Drawing on a new wave of recent research, historian Colin Jones masterfully traces the evolution of Versailles as a space of royal politics and aristocratic pleasures, a building of mythic status, and one of the world’s great tourist destinations. Accessible and compelling, this book is a must-read for all Francophiles.