Promotion

Use code BEST25 for 25% off storewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

City of Light

The Making of Modern Paris

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541673397

Price

$34.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1853, French emperor Louis Napoleon inaugurated a vast and ambitious program of public works in Paris, directed by Georges-Eugè Haussmann, the prefect of the Seine. Haussmann transformed the old medieval city of squalid slums and disease-ridden alleyways into a “City of Light” characterized by wide boulevards, apartment blocks, parks, squares and public monuments, new rail stations and department stores, and a new system of public sanitation. City of Light charts this fifteen-year project of urban renewal which — despite the interruptions of war, revolution, corruption, and bankruptcy — set a template for nineteenth and early twentieth-century urban planning and created the enduring landscape of modern Paris now so famous around the globe.

Lively and engaging, City of Light is a book for anyone who wants to know how Paris became Paris.

Genre:

-

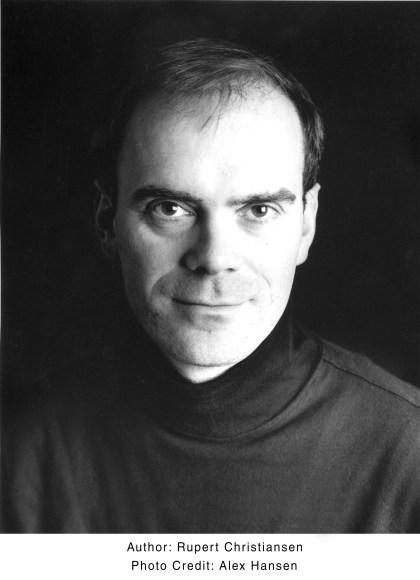

"The demolition and rebuilding of Paris during the Second Empire was, then as now, a subject of impassioned disagreement.... [An] astute, gossipy history."New Yorker

-

"Highly readable... Christiansen grounds Haussmann's story in the political turmoil of the times."Wall Street Journal

-

"Witty, learned and informative...This little book will make you want to walk the expansive elegance of Paris, as well as its back streets, from one end to the other, seeking of French history in the sites it brings so vividly to life."New York Times Book Review

-

"If you are heading for Paris...be sure to put City of Light in your bag...Rupert Christiansen's account of the destruction and rebuilding [of Paris] is masterly-vivid, dramatic...and ultimately tragic."Sunday Times (UK)

-

"Good reading for all lovers of the City of Light."Booklist (starred review)

-

"A concise yet admirably thorough account of the reinvention of one of the world's great cities...Engrossing."Kirkus

-

"A valuable contribution to modern French and urban history."Publishers Weekly

-

"Brisk, vivid, and unexpectedly stirring."Mail on Sunday

-

"Christiansen writes about the streets he clearly loves with wit and élan...Christiansen's splendidly illustrated book made this homesick expat look at Paris with new eyes."Times

-

"If you are heading for Paris...be sure to put City of Light in your bag...Rupert Christiansen's account of the destruction and rebuilding [of Paris] is masterly-vivid, dramatic...and ultimately tragic."Sunday Times

-

"Elegant and gorgeously illustrated."Irish Independent

-

"A history buff's must-bring Parisian travel companion."France Magazine

-

"Detailed.... Christiansen...looks back over this time of major upheaval whose results can still be seen today."France-Amérique

-

"In City of Light, Rupert Christiansen illuminates the tumultuous years of the Second Empire (1852-70) of Napoleon III who, in league with Parisian overlord, Baron Georges Haussmann, rewrote the script for what a modern city should be. Written deftly and with an unfailing eye for colorful detail, City of Light offers an insightful and heartfelt appreciation of the nineteenth-century origins of a world city."Colin Jones, author of Paris: Biography of a City

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use