By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

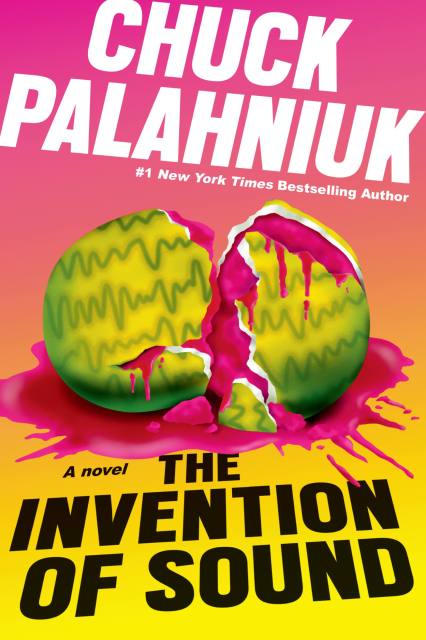

The Invention of Sound

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 8, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538717998

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 8, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A father searching for his missing daughter is suddenly given hope when a major clue is discovered, but learning the truth could shatter the seemingly perfect image Hollywood is desperate to uphold.

Gates Foster lost his daughter, Lucy, seventeen years ago. He’s never stopped searching. Suddenly, a shocking new development provides Foster with his first major lead in over a decade, and he may finally be on the verge of discovering the awful truth.

Meanwhile, Mitzi Ives has carved out a space among the Foley artists creating the immersive sounds giving Hollywood films their authenticity. Using the same secret techniques as her father before her, she’s become an industry-leading expert in the sound of violence and horror, creating screams so bone-chilling, they may as well be real.

Soon Foster and Ives find themselves on a collision course that threatens to expose the violence hidden beneath Hollywood’s glamorous façade. A grim and disturbing reflection on the commodification of suffering and the dangerous power of art, The Invention of Sound is Chuck Palahniuk at the peak of his literary powers — his most suspenseful, most daring, and most genre-defying work yet.

-

PRAISE FOR THE INVENTION OF SOUND:Publishers Weekly

"This dark, humorous tale sparkles with the inventive details -- including a scream powerful enough to crumble buildings -- and provocative insights on the 'commodification of pain' and what it means to turn 'people's basic humanity into something that could be bought and sold.' The result is a wry, devilish delight." -

"Palahniuk expertly balances skewering of cultural institutions with profound insights into the nature of authenticity and the myriad ways we become damaged. The sheer abundance of creative ideas buoyed aloft by the vibrancy of the prose signal a master storyteller energized by delight in his own ingenuity...After his foray into literary advice, Consider This (2020), Palahniuk's heralded return to fiction will galvanize his many avid readers."Booklist

-

PRAISE FOR CHUCK PALAHNIUK:San Francisco Chronicle

"Chuck Palahniuk's stories don't unfold. They hurtle headlong, changing lanes in threes and banging off the guard rails of modern fiction... With his love of contemporary fairytales that are gritty and dirty rather than pretty, Palahniuk is the likeliest inheritor of Vonnegut's place in American writing." -

"One of the most feverish imaginations in American letters."The Washington Post

-

"Like Edgar Allan Poe, Palahniuk is a bracingly toxic purveyor of dread and mounting horror. He makes nihilism fun."Vanity Fair

-

"Dark riffing on modernity is the reason people read Palahniuk. His books are not so much novels as jagged fables, cautionary tales about the creeping peril represented by almost everything."Time

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use