By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

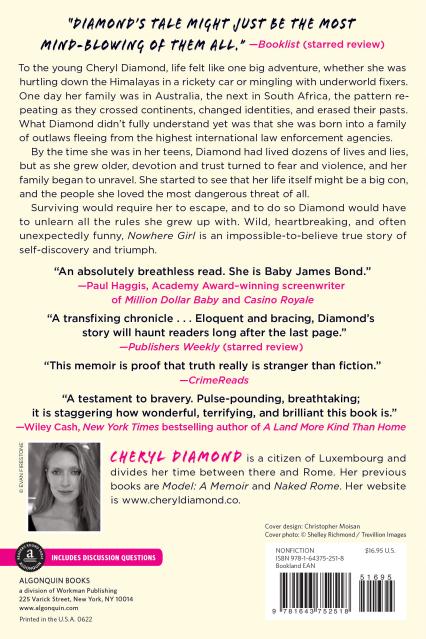

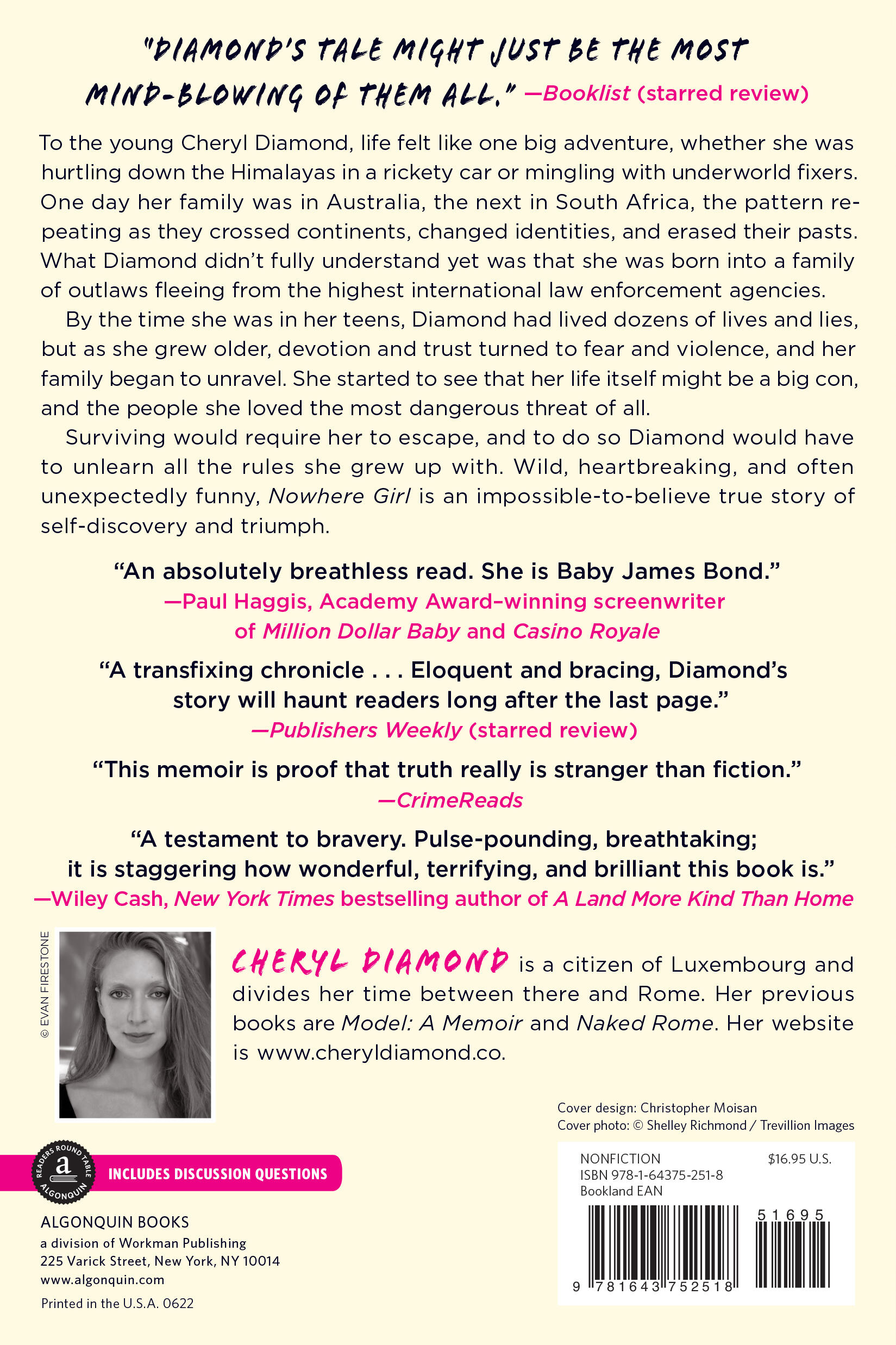

Nowhere Girl

A Memoir of a Fugitive Childhood

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 14, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643752518

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 14, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

To the young Cheryl Diamond, life felt like one big adventure, whether she was hurtling down the Himalayas in a rickety car or mingling with underworld fixers. Her family appeared to be an unbreakable gang of five. One day they were in Australia, the next in South Africa, the pattern repeating as they crossed continents, changed identities, and erased their pasts. What Diamond didn’t yet know was that she was born into a family of outlaws fleeing from the highest international law enforcement agencies, a family with secrets that would eventually catch up to all of them.

By the time she was in her teens, Diamond had lived dozens of lives and lies, but as she grew older, love and trust turned to fear and violence, and her family—the only people she had in the world—began to unravel. She started to realize that her life itself might be a big con, and the people she loved, the most dangerous of all. With no way out and her identity burned so often that she had no proof she even existed, all that was left was a girl from nowhere.

Surviving would require her to escape, and to do so Diamond would have to unlearn all the rules she grew up with. Wild, heartbreaking, and often unexpectedly funny, Nowhere Girl is an impossible-to-believe true story of self-discovery and triumph.

-

"A riveting tale of trauma and resilience."Library Journal “Nowhere Girl beautifully captures the intensity, darkness, and fierce love within an uncompromising outlaw family. Diamond's odyssey would leave the most adventurous among us panting to keep up.”—Alia Volz, author of Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco

I>People

“Like Tara Westover’s Educated, Cheryl Diamond’s memoir tells the harrowing story of how crippling a childhood can be under the despotic narcissistic rule of a controlling father . . . Diamond has a powerful story to tell, and she tells it well, creating strong characters and settings, describing the complicated motivations of her parents and older siblings, all while conveying her yearning for ‘normalcy,’ whatever that is.”

I>New York Journal of Books

“A shocking rollercoaster ride of a story that shares secrets of life on the run but also asks big questions about what family means and who we truly are, no matter what the name on a passport might say.”

I>Town Country

“This memoir is proof that truth really is stranger than fiction.”

B>CrimeReads, “The Most Anticipated Crime Books of 2021: Summer Reading Edition”

“[A] remarkable true story of growing up in a family of outlaws.”

/I>Asheville Citizen-Times

“A transfixing chronicle . . . Propulsive . . . Eloquent and bracing, Diamond’s story will haunt readers long after the last page.”

B>Publishers Weekly, starred review

“A beyond-harrowing memoir . . . Diamond's tale might just be the most mind-blowing of them all.”

B>Booklist, starred review

“Former teen model Diamond reveals a childhood both wacky and cliff-hanging in Nowhere Girl; on the run with an outlaw family, she lived in more than a dozen countries, on five continents, under six assumed identities, by age nine.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use