By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

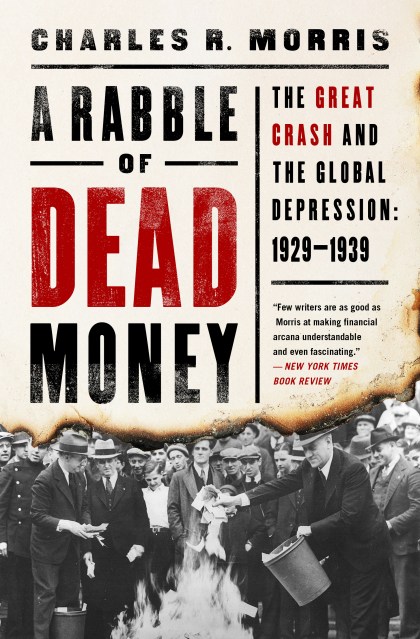

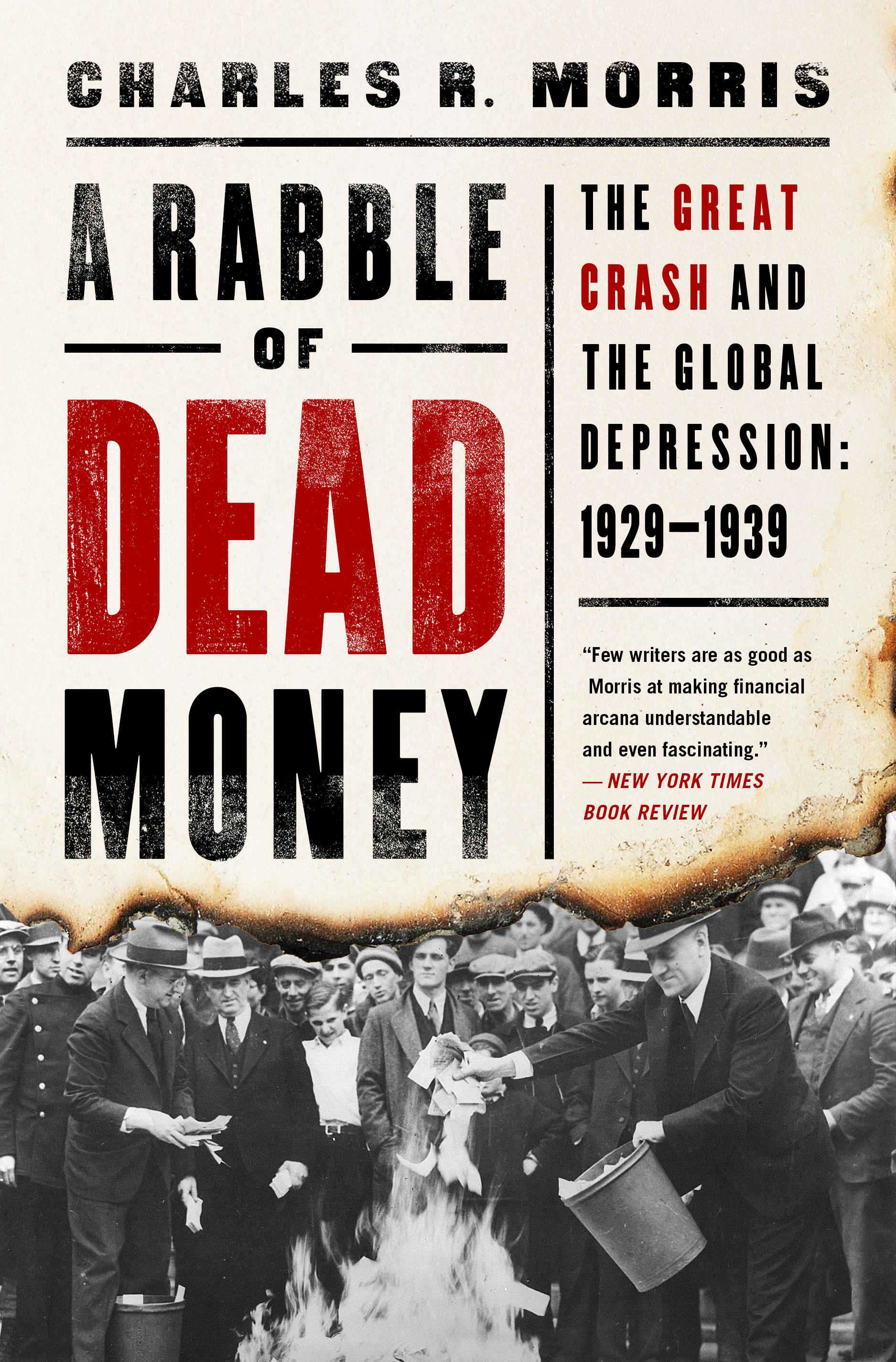

A Rabble of Dead Money

The Great Crash and the Global Depression: 1929–1939

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395359

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this lucid and fast-paced account of the cataclysm, award-winning writer Charles R. Morris pulls together the intricate threads of policy, ideology, international hatreds, and sheer individual cantankerousness that finally pushed the world economy over the brink and into a depression. While Morris anchors his narrative in the United States, he also fully investigates the poisonous political atmosphere of postwar Europe to reveal how treacherous the environment of the global economy was. It took heroic financial mismanagement, a glut-induced global collapse in agricultural prices, and a self-inflicted crash in world trade to cause the Great Depression.

Deeply researched and vividly told, A Rabble of Dead Money anatomizes history’s greatest economic catastrophe — while noting the uncanny echoes for the present.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use