Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

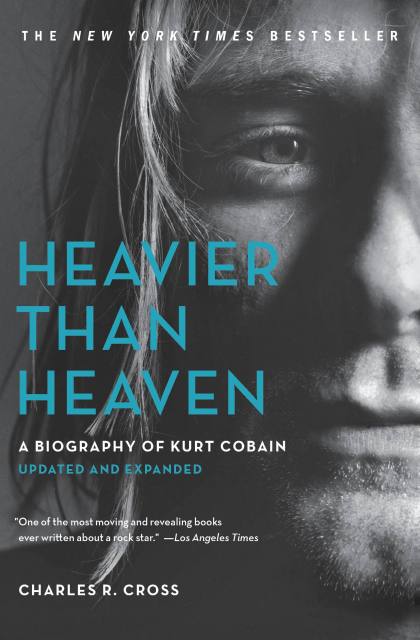

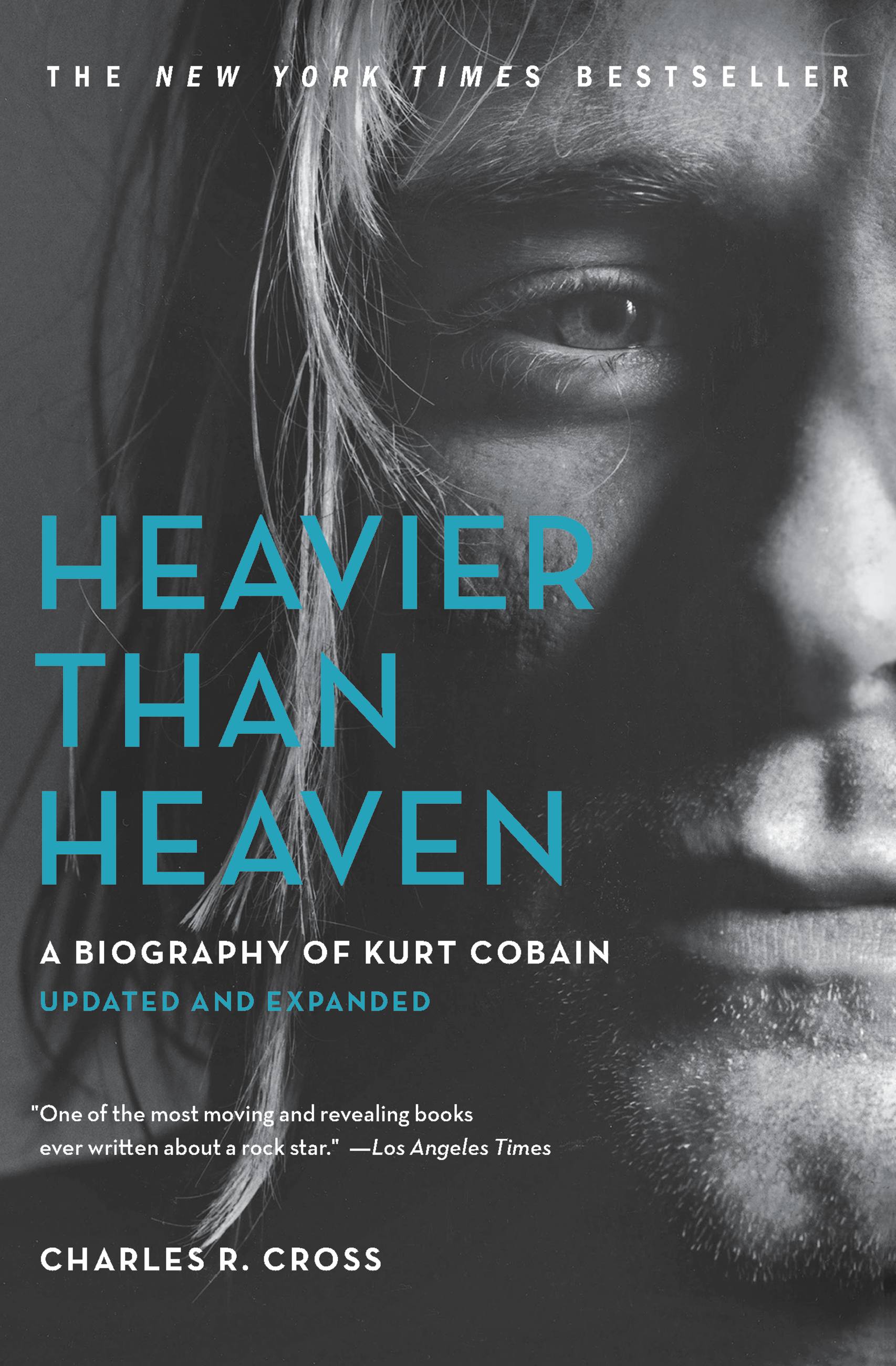

Heavier Than Heaven

A Biography of Kurt Cobain

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

It has been twenty-five years since Kurt Cobain died by his own hand in April 1994; it was an act of will that typified his short, angry, inspired life. Veteran music journalist Charles R. Cross fuses his intimate knowledge of the Seattle music scene with his deep compassion for his subject in this extraordinary story of artistic brilliance and the pain that extinguished it. Based on more than four hundred interviews; four years of research; exclusive access to Cobain’s unpublished diaries, lyrics, and family photos; and a wealth of documentation, Heavier Than Heaven traces Cobain’s life from his early days in a double-wide trailer outside of Aberdeen, Washington, to his rise to fame, success, and the adulation of a generation. Charles Cross has written a new preface for this edition, giving readers context for the time in which the book was written, six years after Kurt’s death, and reminding everyone how fresh that cultural experience was when the interviews for the book were done. The new final chapter will update the story since, regarding investigations into Cobain’s death, Nirvana’s induction into the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame, and how their place in rock history has only risen over the decades.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2012

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401304515

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use