By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

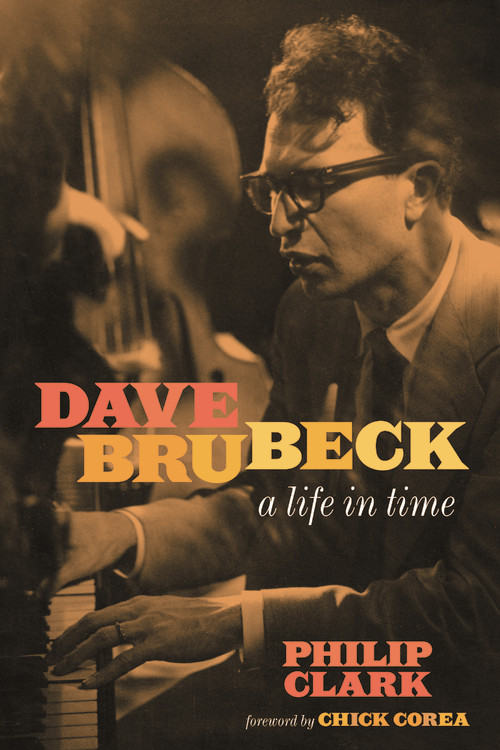

Dave Brubeck

A Life in Time

Contributors

By Philip Clark

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 15, 2022

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306921667

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 15, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 2003, music journalist Philip Clark was granted unparalleled access to jazz legend Dave Brubeck. Over the course of ten days, he shadowed the Dave Brubeck Quartet during their extended British tour, recording an epic interview with the bandleader. Brubeck opened up as never before, disclosing his unique approach to jazz; the heady days of his “classic” quartet in the 1950s-60s; hanging out with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Miles Davis; and the many controversies that had dogged his 66-year-long career.

Alongside beloved figures like Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra, Brubeck’s music has achieved name recognition beyond jazz. But finding a convincing fit for Brubeck’s legacy, one that reconciles his mass popularity with his advanced musical technique, has proved largely elusive. In Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, Clark provides us with a thoughtful, thorough, and long-overdue biography of an extraordinary man whose influence continues to inform and inspire musicians today.

Structured around Clark’s extended interview and intensive new research, this book tells one of the last untold stories of jazz, unearthing the secret history of “Take Five” and many hitherto unknown aspects of Brubeck’s early career – and about his creative relationship with his star saxophonist Paul Desmond. Woven throughout are cameo appearances from a host of unlikely figures from Sting, Ray Manzarek of The Doors, and Keith Emerson, to John Cage, Leonard Bernstein, Harry Partch, and Edgard Varèse. Each chapter explores a different theme or aspect of Brubeck’s life and music, illuminating the core of his artistry and genius. To quote President Obama, as he awarded the musician with a Kennedy Center Honor: “You can’t understand America without understanding jazz, and you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.”

-

"Biography, social history, musicological exploration ... this wonderful book is many things. But above all, it is a sort of intoxicating literary jam session. Words and sentences spit and spin and swing, creating rhythms and harmonies worthy of Brubeck himself. The sheer descriptive verve, page after page, made me want to listen to every single musical example cited. A major achievement."STEPHEN HOUGH, classical pianist and composer

-

"This is the writing about jazz that we've been waiting for. By keeping the music at the center, and interweaving the background of cultural, political and social change to illuminate the development of the music, Clark gives us a complete picture of the artist's life and work."MIKE WESTBROOK, jazz pianist and composer

-

"DAVE BRUBECK: A Life in Time is about the timeless life of the inspired and inspiring jazz master Dave Brubeck. This biography, written with love and passion, is a landmark document that is insightful and inspiring all in itself. Bravo!"JOE LOVANO, jazz saxophonist

-

"A nontraditional biography that sings...as unconventional and compelling as its subject."KIRKUS REVIEWS

-

"A concise but comprehensive biography... [Clark] hits the right notes for die-hard Brubeck disciples and jazz neophytes alike."PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

-

"[A] remarkable biography... [Clark writes] intelligently and joyously... [and] fittingly, for a Brubeck biography, this is also a multifarious work; adventurous with narrative and structure."MOJO

-

"The emphasis on the technical side of Brubeck's music, and on Brubeck's impact on rock and other nonjazz music, is thought provoking."BOOKLIST

-

"[This book] is that rare beast: an uncompromisingly analytical study that absorbs and entertains, illuminating both its subject and his social context."LONDON JAZZ NEWS

-

"A brilliant book."JAZZ PROFILES

-

"[A]n engaging new biography... we feel the grain and texture and historical weight of single moments, but only because we also understand the larger picture. It's a rare jazz biography that gives us both, so eloquently."THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

-

"Time Out may be what Brubeck (1920-2012) is known for, but, as Philip Clark reveals in Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, it is merely the highlight of his long career as a composer, pianist and bandleader. Mr. Clark, a British music journalist, has been writing about Brubeck for more than 20 years. The present book is a crystallization of an interview he conducted with his subject over the course of several days in 2003, supplemented by further interviews with Brubeck, his family, his musicians and associates, and extensive research in the Brubeck archives. Thorough and authoritative, Mr. Clark has done a great service to his subject's legacy."The Wall Street Journal

-

"Richly detailed... a great achievement."The Wire

-

"An articulate, scrupulously-researched account based on first-hand information, this book presents Brubeck's contribution to music with the critical insight that it deserves."BBC Music Magazine

-

"Compelling... By starting in [Brubeck's] autumnal years, the book almost cinematically conjures flashbacks to the past, which get fleshed out by interviews along the way."Jazz Times

-

"Detailed, informed and engaging... Philip Clark's revealing study enables a deeper and more complete understanding of this artist and pioneer's life and work."Gramophone

-

"It's hard to imagine anyone more qualified to write a Brubeck bio than Philip Clark, who spent long periods of time with the man, his band members, and his wife Iola; had unlimited access to his papers and correspondence; and has been a flag-waving fan of the music for ages. His book contains a head-spinning amount of detail bordering on micro-history, with in-depth accounts of recording dates and tours going back to the beginning, as well as the kind of musical analysis that could only have come from years of close listening. To call it 'exhaustive' is to undersell it."The Los Angeles Review of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use