Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

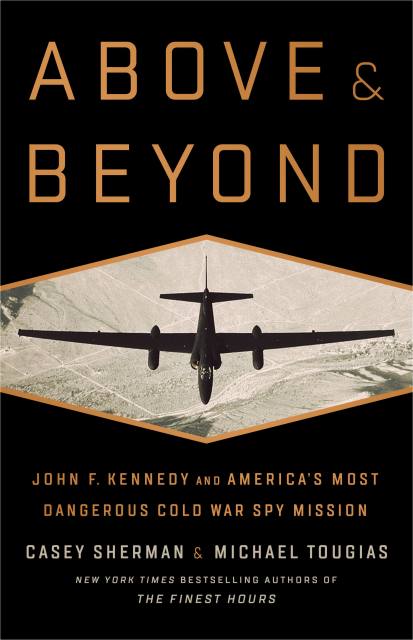

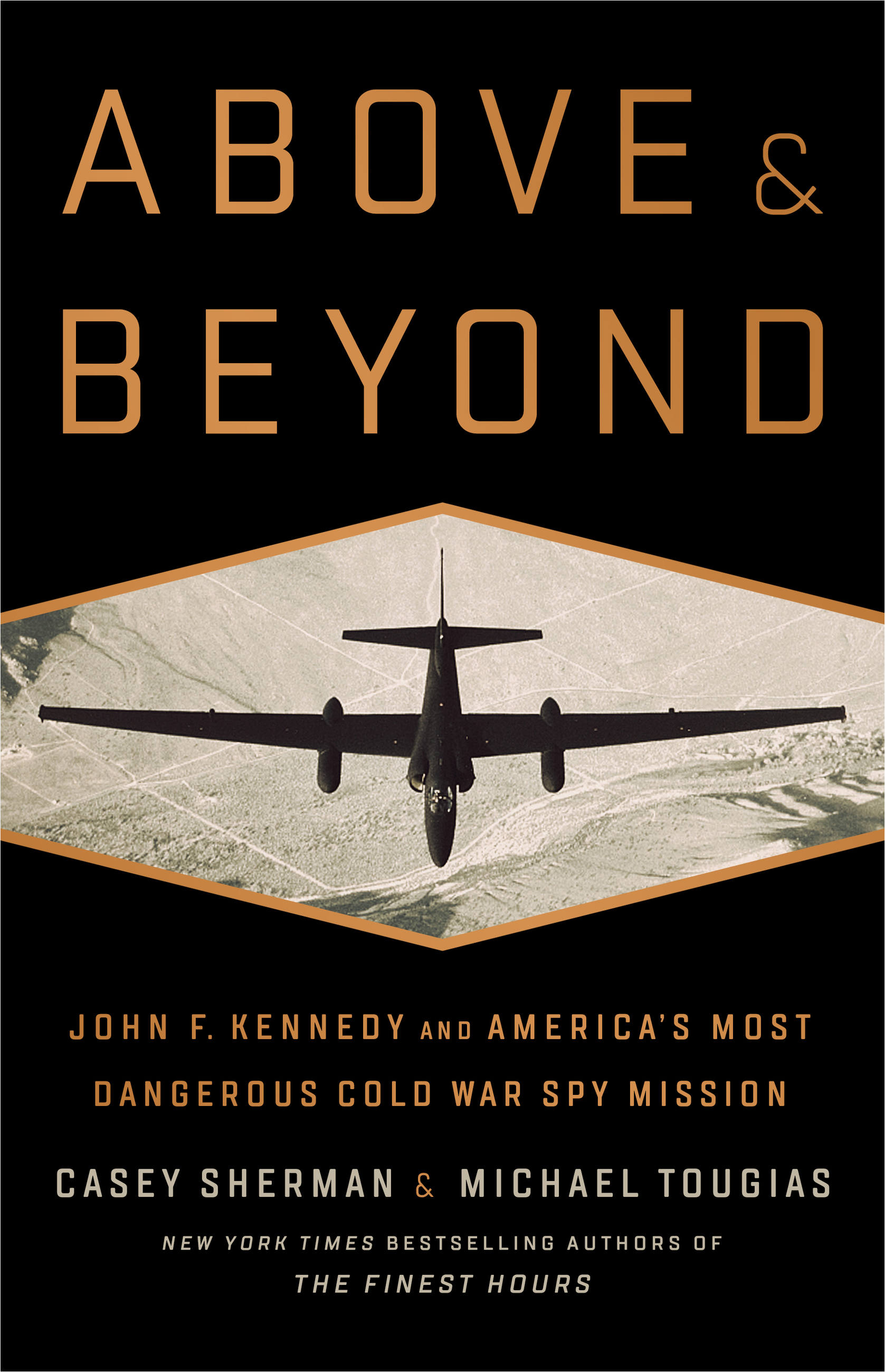

Above and Beyond

John F. Kennedy and America's Most Dangerous Cold War Spy Mission

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 17, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610398053

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 17, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

During the ominous two weeks of the Cold War’s terrifying peak, two things saved humanity: the strategic wisdom of John F. Kennedy and the U-2 aerial spy program.

On October 27, 1962, Kennedy, strained from back pain, sleeplessness, and days of impossible tension, was briefed about a missing spy plane. Its pilot, Chuck Maultsby, was on a surveillance mission over the North Pole, but had become disoriented and steered his plane into Soviet airspace. If detected, its presence there could be considered an act of war.

As the president and his advisers wrestled with this information, more bad news came: another U-2 had gone missing, this one belonging to Rudy Anderson. His mission: to photograph missile sites over Cuba. For the president, any wrong move could turn the Cold War nuclear.

Above and Beyond is the intimate, gripping account of the lives of these three war heroes, brought together on a day that changed history.

Selected as a “Top 10 Nonfiction Books to Read” (2018) by the MA Book Awards

Genre:

-

"The authors eloquently convey the difficulties and tensions involved in the [U-2] flights, dramatically magnified during the crisis, when miscalculations could instigate disastrous response by either side....This superbly written, tense, and sometimes sad account views the Cuban Missile Crisis from an unusual and telling perspective."Booklist, starred

-

"Unfolds like a spy thriller and serves as an unnerving cautionary tale in a time of reckless brinksmanship."Boston Globe

-

"A novelistic approach that involves dramatically recreated scenes and interweaving story lines... The focus on two lesser-known figures gives the book an added dimension beyond other Cuban Missile Crisis histories....[Above & Beyond] hums when describing the strategic maneuvering in Washington.... The authors will leave readers with a greater appreciation of the work required to combat the 'miscalculations, incorrect interpretations, and breakdowns in command and control that could lead to war'."Publishers Weekly

-

"Sherman and Tougias present an absorbing account of heroic U-2 pilots Rudolph Anderson and Charles Maultsby and their harrowing missions.... Fascinating."Library Journal

-

"The authors have assembled a page-turning narrative. An edifying history that, given America's current global diplomatic stance, is also timely and hopefully instructive to those faced with similarly dire circumstances."Kirkus Reviews

-

"A you-are-there retelling of the Cold War's scariest hours."Military Times

-

"A fast-paced read with exciting recollections of this tumultuous time guaranteed to keep you on the edge of your seat....thrilling and nerve-wracking....Even though you know the outcome, it's still enough to get the heart pounding and palms sweating as Kennedy ponders and the U-2 pilots soar into the cross-hairs of history."Providence Journal

-

"Readers get a front row seat to a dramatic moment in history."Cape Cod Times

-

"Here is the Cuban Missile Crisis as you've never seen it before: through the eyes of the men who flew over the island at 72,000 feet, photographing the missiles that confronted Kennedy with the real possibility of nuclear war. Sherman and Tougias tell their story with pace, riveting new detail, and tremendous economy of style. To be read at one sitting with a stiff Scotch at your elbow."Giles Whittell, New York Times bestselling author of Bridge ofSpies

-

"Above and Beyond is a thrilling, inspiring story that would make for relevant reading in any era, but today feels essential. It takes you inside the rooms, inside the cockpits, and sometimes inside the minds of the people confronting the most dangerous moments in human history. A tribute to true patriotism and courage, this bookreminds us that the bravest warriors, the ones who make the biggest differences, are often the ones who never fire a shot."Jeffrey E. Stern, coauthor of The 15:17 to Paris

-

"The Cuban Missile Crisis: it may be the most terrifying thirteen days in human history. Live it again in Above and Beyond, the riveting new book by Casey Sherman and Michael J. Tougias. Climb aboard the most famous spy plane of them all, the legendary U-2, and photograph missile sites. Take a seat in the White House Situation Room to deliberate with President Kennedy on those photographs. Turn the pages all night and marvel yet again at the intrepid bravery of those pilots, and at the leadership that was calm, thoughtful, and steady, yet resolute in the face of unimaginably high stakes. It's an adventure yarn worthy of a great spy novelist and a cautionary tale for our dangerous times."William Martin, New York Times bestselling author of Back Bayand Bound for Gold

-

"Intriguing... reassuring and disquieting. Reminds us of how resilient, inspired and successful American military, industrial and political leadership could be in the direst days of the Cold War."Wall Street Journal

-

"Just when you think the story can't get any better there is a cover-up."The Patriot Ledger

-

"An exciting account of the Cuban Missile Crisis with plenty of detail about the spyplanes and the brave men who flew them...The authors of the best-selling The Finest Hours have worked their magic again with this engaging true-life thriller."Aviation History