By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

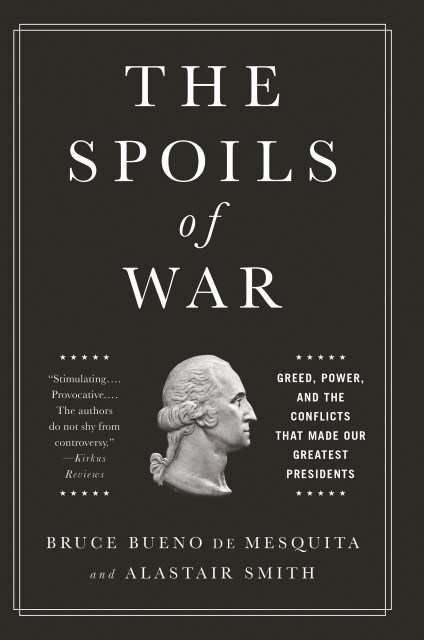

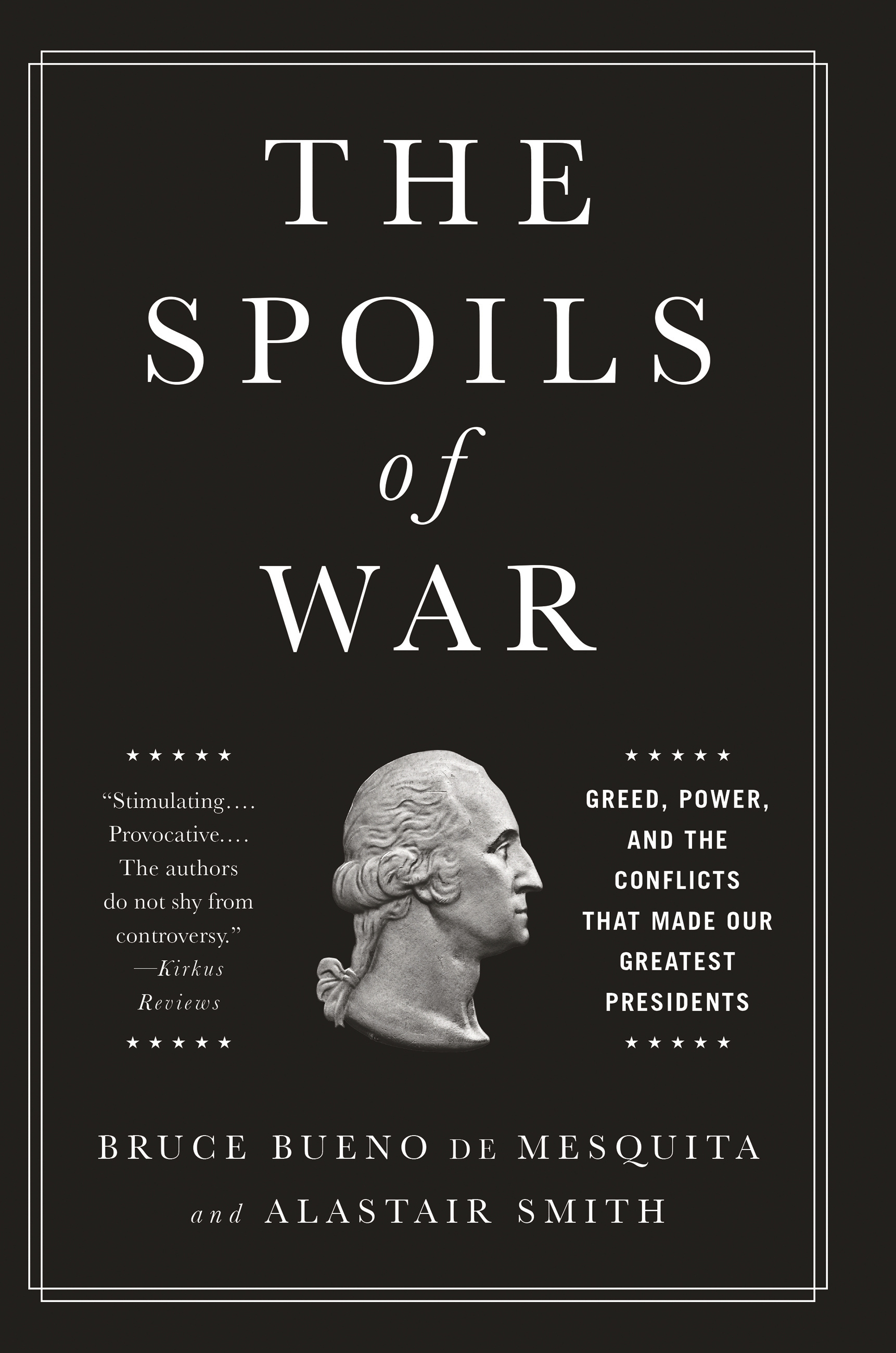

The Spoils of War

Greed, Power, and the Conflicts That Made Our Greatest Presidents

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2016

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396622

Price

$27.99Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.99 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It’s striking how many of the presidents Americans venerate-Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy, to name a few-oversaw some of the republic’s bloodiest years. Perhaps they were driven by the needs of the American people and the nation. Or maybe they were just looking out for themselves.

This revealing and entertaining book puts some of America’s greatest leaders under the microscope, showing how their calls for war, usually remembered as brave and noble, were in fact selfish and convenient. In each case, our presidents chose personal gain over national interest while loudly evoking justice and freedom. The result is an eye-opening retelling of American history, and a call for reforms that may make the future better.

Bueno de Mesquita and Smith demonstrate in compelling fashion that wars, even bloody and noble ones, are not primarily motivated by democracy or freedom or the sanctity of human life. When our presidents risk the lives of brave young soldiers, they do it for themselves.

Genre:

-

"This entertaining read, which still pushes significant empirical value related to American history and the presidency, leads its audience to question the actual nobility of even the most idolized American presidents. A daring work designed for a wide audience."CHOICE

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use