By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

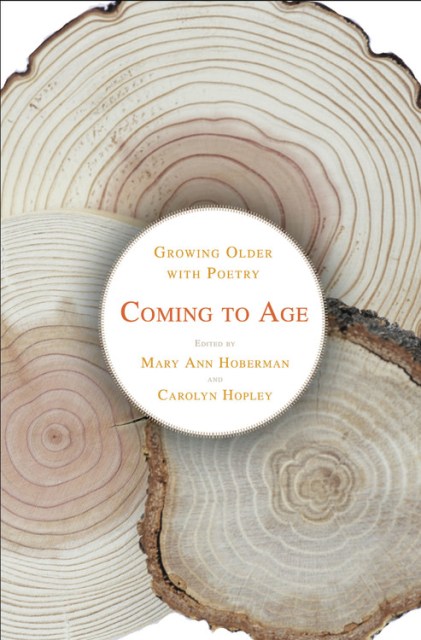

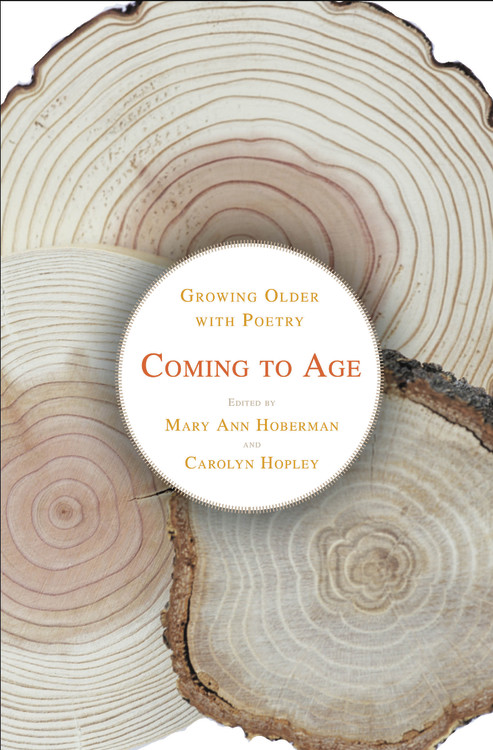

Coming to Age

Growing Older with Poetry

Contributors

Edited by Carolyn Hopley

Edited by Mary Ann Hoberman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316424912

Price

$25.00Price

$31.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.00 $31.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

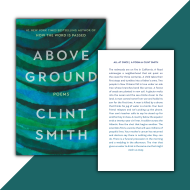

This exquisitely giftable anthology of poems about age and aging reveals the wisdom of trailblazing writers who found power and growth later in life.

At eighty-two, the novelist Penelope Lively wrote: “Our experience is one unknown to most of humanity, over time. We are the pioneers.” Coming to Age is a collection of dispatches from the great poet-pioneers who have been fortunate enough to live into their later years.

Those later years can be many things: a time of harvesting, of gathering together the various strands of the past and weaving them into a rich fabric. They can also be a new beginning, an exploration of the unknown. We speak of “growing old.” And indeed, as we too often forget, aging is growing, growing into a new stage of life, one that can be a fulfillment of all that has come before.

To everything there is a season. Poetry speaks to them all. Just as we read newspapers for news of the world, we read poetry for news of ourselves. Poets, particularly those who have lived and written into old age, have much to tell us. Bringing together a range of voices both present and past, from Emily Dickinson and W. H. Auden to Louise Gluck and Li-Young Lee, Coming to Age reveals new truths, offers spiritual sustenance, and reminds us of what we already know but may have forgotten, illuminating the profound beauty and significance of commonplace moments that become more precious and radiant as we grow older.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use