By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

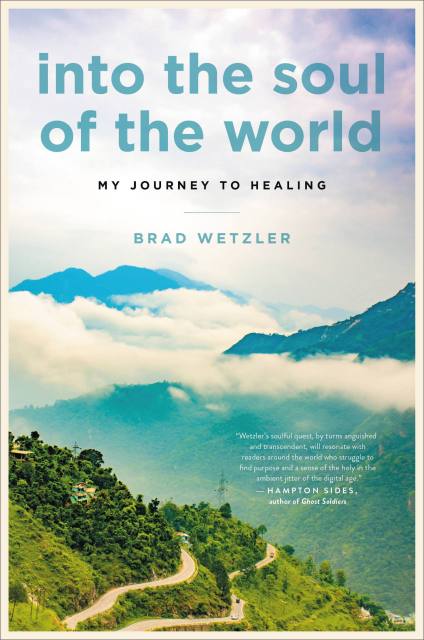

Into the Soul of the World

My Journey to Healing

Contributors

By Brad Wetzler

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 21, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780306829307

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 21, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This powerful memoir shares an adventure journalist’s story of a decade-long, round-the-world quest to overcome his drug addiction and to understand and heal from past traumas.

Suffering from PTSD and severe depression from past trauma, battling an addiction to overprescribed psychiatric medication, and at the rock bottom of his career, journalist Brad Wetzler had nowhere to go. So he set out on a journey to wander and hopefully find himself—and the world—again.Into the Soul of the World is Wetzler’s thrilling, impactful, and heartrending memoir of healing—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. An adventure journalist at heart, Wetzler mixes travelogue with empowering insights about his inner journey to better care for his own mental health. Journey with him as he travels across Israel and the West Bank, before moving on to India, a candle-lit cave on a mountaintop in the Himalayan foothills, and a life-changing encounter with a 100-year-old yogi.

Wetzler’s writing is full of the poignant, amusing, and occasionally heart‑breaking situations that unfold when we finally decide to confront depression (or any mental health struggle) and declare ourselves ready to heal: How do we heal our past and thrive again? What does it mean to live a good life? How can we transform our suffering and serve others? His answer: live to tell the story and find the humility and courage to be the best human you can be.

-

"As a far-flung journalist and celebrated editor, Brad Wetzler has led the very definition of an adventurous life, but in Into the Soul of the World, he gives an unflinching account of his interior adventures. Wetzler's soulful quest, by turns anguished and transcendent, will resonate with readers around the world who struggle to find purpose and a sense of the holy in the ambient jitter of the digital age."Hampton Sides, author of Ghost Soldiers

-

"Reading Brad Wetzler’s Into the Soul of the World is like embarking on a thrilling, dangerous journey—rivering straight into the heart of what matters most—to find yourself transformed. Ever the seeker, Wetzler wrestles with dark family secrets and triggered trauma, redefining what it means to be a man and spiritual being living in the twilight of our hyper-American materialism. If Into the Soul of the World belongs on a shelf next to Eat, Pray, Love, what lingers is Wetzler’s relentless audacity to try to tell the truth, however uncomfortable—about families and lovers and our times—In hopes of setting himself, and us, free."Michael Paterniti, author of Driving Mr. Alpert and The Telling Room

-

"In the age of toxic masculinity, Brad Wetzler's Into the Soul of the World offers a powerful, profound, and deeply personal road map for actively cultivating a different kind of manhood. Through energetic and lively prose, Wetzler takes us inside the heart and mind of a man who refuses to conform to society's restrictive notion of manhood, and instead presents a new path for men to walk."Emily Rapp Black, author of The Still Point of the Turning World

-

"I've followed Brad Wetzler's travels around the globe with envy and admiration for more than two decades. He lived the dream. He also was living a lie, one that nearly destroyed him. Into the Soul of the World is his beautiful, terrifying, and witty travelogue, an essential chronicle of a life-saving journey into oneself."Mark Adams, author of Tip of the Iceberg

-

"A tale of heart-wrenching honesty and, ultimately, liberating compassion, this is a book that will change the lives of those yearning to find their own way back into the soul of the world."Sarah Bird, author of Last Dance on the Starlight Pier

-

"Brad Wetzler is a born storyteller and a true seeker. His beautiful book reads like a trip to hell and back, with glimpses of paradise along the way. Wetzler is willing to climb the mountain, swim the river, crawl into the cave: whatever it takes to get some truth. As a result, Into the Soul of the World is an exhilarating read--an honest record of an adventurous life and a moving window into the soul of a human being."Clint Willis, journalist, editor, and author of The Boys of Everest

-

"Into the Soul of the World is full of an admirable power and urgency. A part of the book’s soul is how wide-ranging the story is in its exploration of trauma, bringing in not only psychology but an intelligent and sensitive telling of Wetzler’s own life, along with many fascinating religious, spiritual, and philosophical excursions.”David Gilbreath Barton, psychotherapist and author of Havel: Unfinished Revolution

-

"After three decades of writing adventure stories, Brad Wetzler now delivers the ultimate adventure: a brave, big-hearted journey through trauma to self-transformation. For anyone and everyone faced with similar challenges, this is not just a book; it's a lamp to illuminate the rocky, painful, redemptive path forward."Daniel Coyle, author of The Talent Code and The Culture Code

-

“A quest for healing, one adventure at a time.”The New York Post

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use