Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

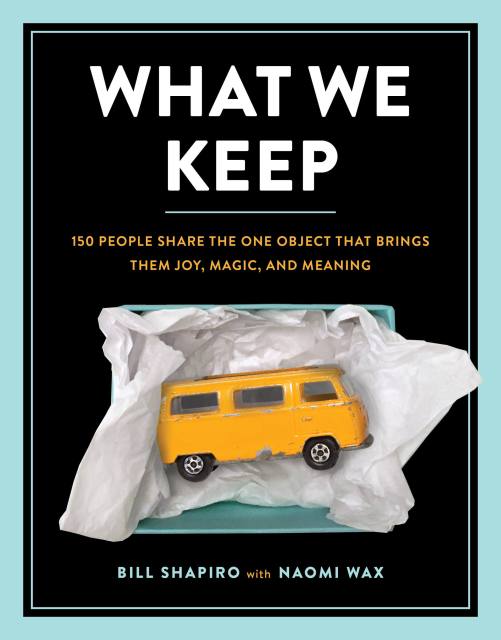

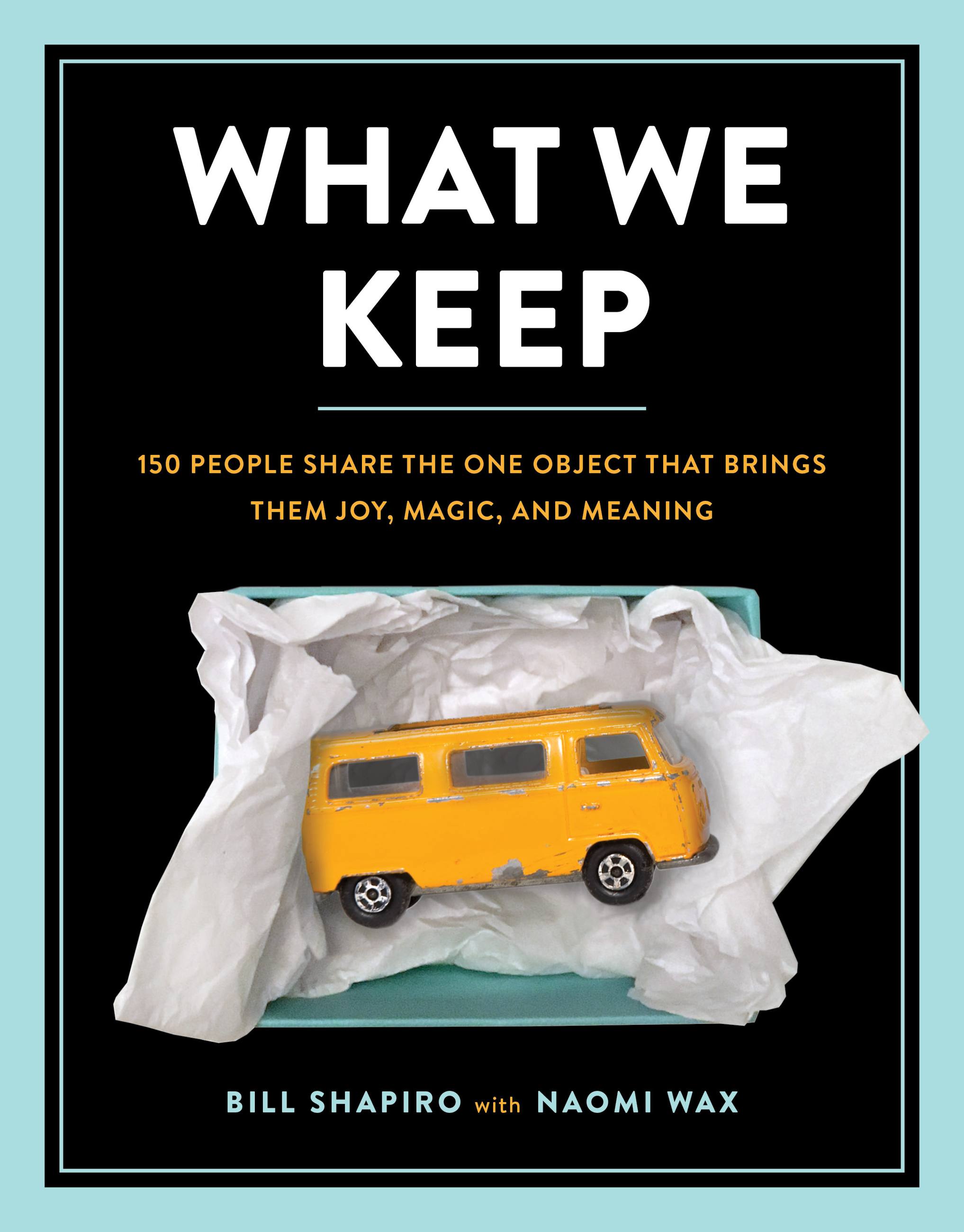

What We Keep

150 People Share the One Object that Brings Them Joy, Magic, and Meaning

Contributors

By Bill Shapiro

By Naomi Wax

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.00 $32.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 25, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

All of us have that one object that holds deep meaning–something that speaks to our past, that carries a remarkable story. Bestselling author Bill Shapiro collected this sweeping range of stories–he talked to everyone from renowned writers to Shark Tank hosts, from blackjack dealers to teachers, truckers, and nuns, even a reformed counterfeiter–to reveal the often hidden, always surprising lives of objects.

Genre:

-

"From the former editor-in-chief of Life Magazine comes this gorgeous photo collection of everyday things that people hold dear. A combination of fascinating interviews and photographs introduce readers to the most personal items owned by notable individuals including Cheryl Strayed, Melinda Gates, and Mark Cuban, all while examining the reasons we consider certain possessions invaluable."Real Simple, 'The Best Books of 2018 (So Far)

-

"Our no-fail host gift? A book that's instantly absorbing yet easy to dip in and out of. This season, that book is What We Keep, a collection of interviews with a cast of personalities - some famous, others merely fascinating - about the objects they cherish above all others."Sunset

-

"[A] moving new book, What We Keep, offers a meditation on the distinctly human need to find meaning in the inanimate."Fast Company

- On Sale

- Sep 25, 2018

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762462551

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use