Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

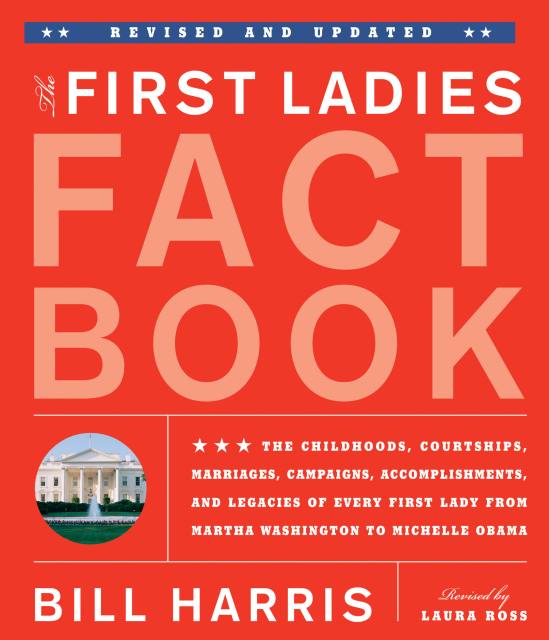

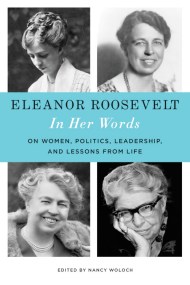

First Ladies Fact Book -- Revised and Updated

The Childhoods, Courtships, Marriages, Campaigns, Accomplishments, and Legacies of Every First Lady from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama

Contributors

By Bill Harris

By Laura Ross

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 1, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The First Ladies Fact Book is a comprehensive, fascinating, and intimate look at the life of each first lady from Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Each profile includes a portrait, key biographical information, and several additional photographs. For each of this historically important women, you’ll learn key facts about their childhood and upbringing, early careers, the path to the White House, their impact on the role and the country, and post-FLOTUS highlights.

Whether you’re browsing, preparing for a tough quiz night or for a classroom report, The First Ladies Fact Book combines the rich facts with fascinating details for history buffs of all ages.

Pick-up the companion title, The President’s Fact Book — Revised and Updated.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 1, 2013

- Page Count

- 752 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9781603763134

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use