Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

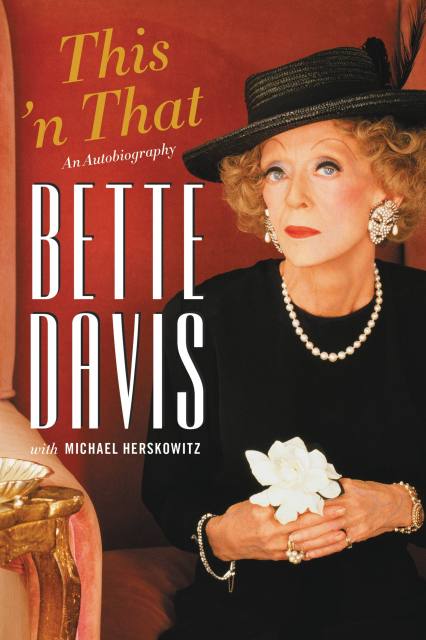

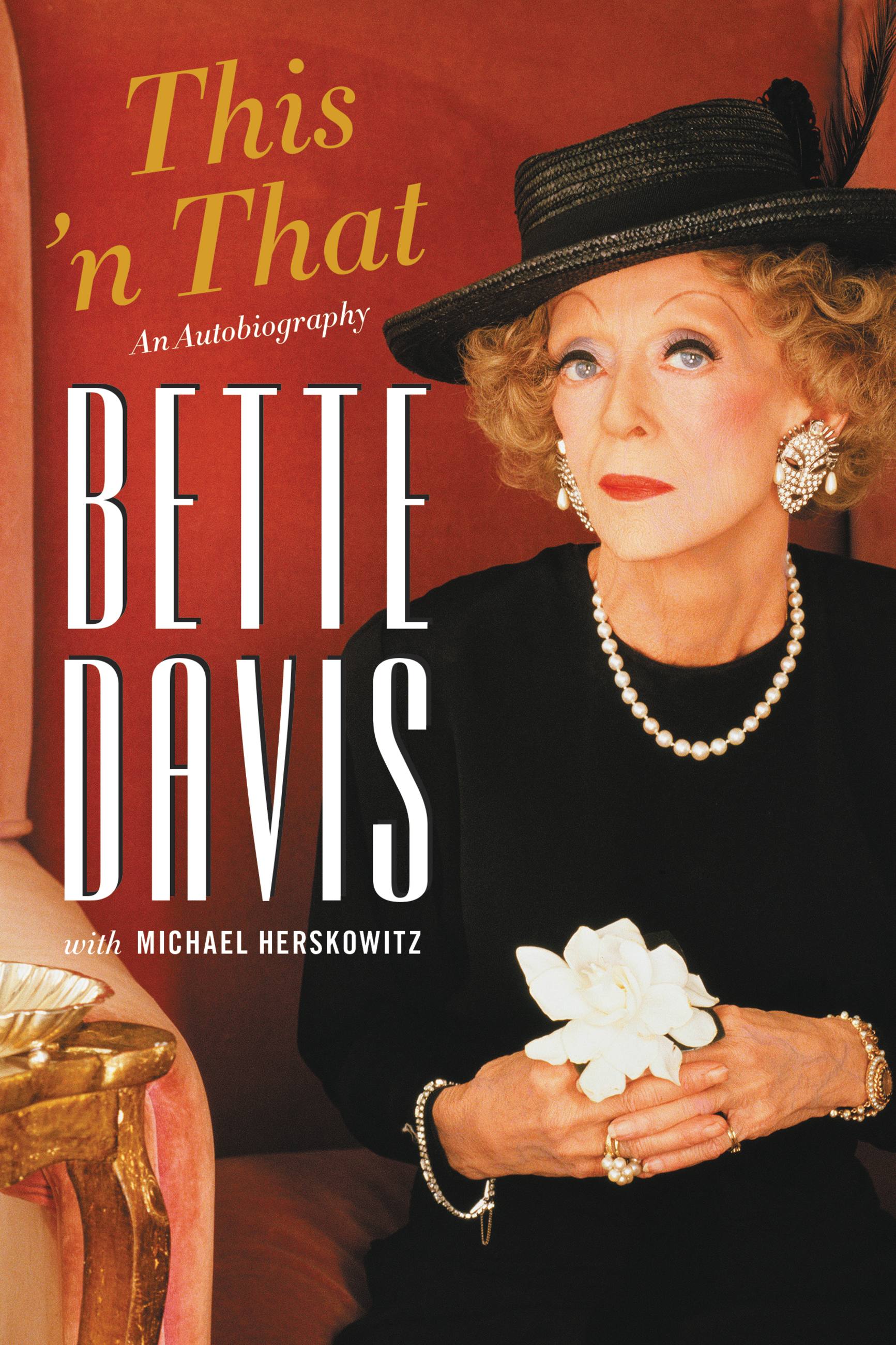

This 'n That

Contributors

By Bette Davis

With Michael Herskowitz

Formats and Prices

Price

$4.99Price

$5.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook (Digital original) $4.99 $5.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A woman of strong appetites and opinions, Bette Davis minces no words. In frank, no nonsense terms she talks about the stroke that nearly killed her, and inspires us with the story of her subsequent recovery from cancer–a lively and encouraging account shot through with the star’s unique blend of spunk and wit.

Davis was famous for being as unsparing of herself as she was of others. Among the “others” of this book are President Ronald Reagan, who was a contract player at Warner Bros. when she was; Joan Crawford, her costar in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?; Humphrey Bogart; Marilyn Monroe; Elizabeth Taylor; and Helen Hayes, Bette’s costar in her first film after her illness, Murder with Mirrors. She also talks about her deep friendship with her longtime assistant, Kathryn Sermak, who nursed Davis back to health after her stroke and ushered her back into acting when Davis’s doctors thought all hope was lost.

As Davis says, “If everyone likes you, you’re doing your job wrong.” This is a unique and controversial book by one of the most incandescent and unconventional acting talents of all time, as magnetic and supremely talented as the lady herself.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2017

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316441261

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use