Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

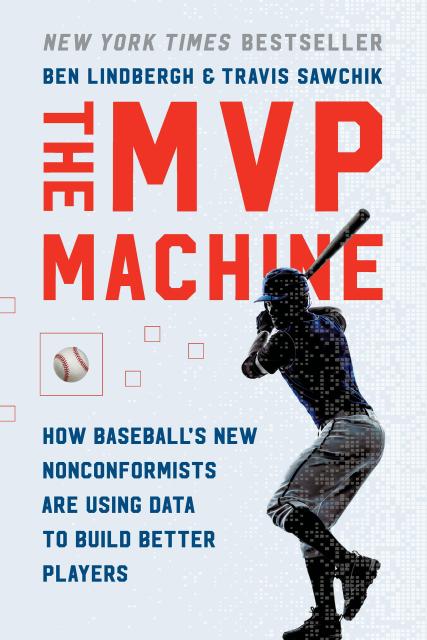

The MVP Machine

How Baseball's New Nonconformists Are Using Data to Build Better Players

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 4, 2019

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541698956

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 4, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Move over, Moneyball―this New York Times bestseller examines major league baseball's next cutting-edge revolution: the high-tech quest to build better players.

"A convincing, and faith-restoring, case that genuine, unadulterated miracles can happen in baseball."―Washington Post

As bestselling authors Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik reveal in the New York Times–bestselling The MVP Machine, the Moneyball era is over. Over twenty years after Michael Lewis brought the Oakland Athletics’ groundbreaking team-building strategies to light, every front office takes a data-driven approach to evaluating players. But instead of out-drafting, out-signing, and out-trading their rivals, baseball’s best minds have turned to out-developing opponents, gaining greater edges than ever by perfecting prospects and eking extra runs out of older athletes who were once written off. From the latest trends in player development to the fallout from baseball’s sign-stealing scandal, Lindbergh and Sawchik take us inside the transformation of baseball, teaching, and talent.

The MVP Machine not only charts the future of a sport but also offers a lesson that goes beyond baseball. Success stems not from focusing on finished products, but from making the most of untapped potential.

"A convincing, and faith-restoring, case that genuine, unadulterated miracles can happen in baseball."―Washington Post

As bestselling authors Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik reveal in the New York Times–bestselling The MVP Machine, the Moneyball era is over. Over twenty years after Michael Lewis brought the Oakland Athletics’ groundbreaking team-building strategies to light, every front office takes a data-driven approach to evaluating players. But instead of out-drafting, out-signing, and out-trading their rivals, baseball’s best minds have turned to out-developing opponents, gaining greater edges than ever by perfecting prospects and eking extra runs out of older athletes who were once written off. From the latest trends in player development to the fallout from baseball’s sign-stealing scandal, Lindbergh and Sawchik take us inside the transformation of baseball, teaching, and talent.

The MVP Machine not only charts the future of a sport but also offers a lesson that goes beyond baseball. Success stems not from focusing on finished products, but from making the most of untapped potential.

-

"In The MVP Machine, Lindbergh and Sawchik make a convincing, and faith-restoring, case that genuine, unadulterated miracles can happen in baseball."Washington Post

-

"Even MBAs who don't know what an ERA ... will grasp the book's essential message: next-generation technologies and analytics radically transform top-tier talent development and technique."Harvard Business Review

-

"The MVP Machine is an eye-opening dispatch from the leading edge of the sport."The Atlantic

-

"The MVP Machine (Basic Books), out now, tells how a series of new tools, advanced statistics and technology are changing the game of baseball, led by innovators."New York Post

-

"For too long, stat geeks like me ignored the 'development' side of 'scouting and development.' The MVP Machine is the book that's going to change that. Travis Sawchik and Ben Lindbergh persuasively and entertainingly demonstrate that a baseball player's success is less about God-given talent and more about innovation, hard work, and the willingness to take a more scientific approach to the game. Read it, and you won't think about baseball in quite the same way again."Nate Silver, founder of FiveThirtyEight

-

"I wish this book spent more time on the Red Sox winning four times as many titles as the Yankees this century, but The MVP Machine is a great and informative deep dive on the challenges of unlocking talent and building winning teams in the age of analytics."Bill Simmons, founder and CEO, The Ringer

-

"High-speed cameras and radar-tracking devices have revolutionized training and are now giving baseball pitchers accurate, detailed and actionable feedback during practice. This captivating book details step-by-step how merely good major league pitchers have recently been able to transform themselves into great ones and reach previously unattainable levels of mastery by purposeful and deliberate practice."K. Anders Ericsson, Conradi Eminent Scholar of Psychology, Florida State University, and author of Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise

-

"In today's game, players and teams are doing more than ever behind the scenes to change and improve. The work they do is absolutely critical to success but nearly invisible to the public -- until now. Any fan seeking a fresh look at how teams win in modern baseball should read this book."Chaim Bloom, President, Baseball Operations, St. Louis Cardinals

-

"The MVP Machine isn't just the purest distillation yet of baseball's information era and how it came to be. It's a seminal road map for the game today and treasure map to find -- and understand -- the gems baseball soon will offer."Jeff Passan, MLB insider, ESPN

-

"This is the book baseball needed, the definitive document on how the best players in the world are using new ideas to become even better. Until now, no one had delivered an authoritative, comprehensive look at the revolution that is transforming the sport and offering lessons that extend even beyond the field. If you want to understand the inner workings of the modern game, you must read The MVP Machine."Ken Rosenthal, baseball reporter for The Athletic and Fox Sports

-

"Travis Sawchik and Ben Lindbergh brilliantly capture the next frontier of major-league teams' 'evolve or die' mindset: the league-wide movement of using data, technology, and science to revolutionize the way players are developed. Baseball has seen a rapid influx of high-curiosity, growth-mindset players and coaches, creating the perfect environment for innovation and rethinking convention. The MVP Machine provides tremendous insight into baseball's latest transformation."Billy Eppler, special advisor for the Milwaukee Brewers

-

"As the game of baseball, and more specifically the teaching methods within, continue to evolve, The MVP Machine paints a real-time portrait of player development. Players and coaches are in a constant search for advantages that will push their personal limits on the field in order to maximize their abilities. Ben and Travis provide fascinating details of how individual players pushed the boundaries of innovative coaching, self-reflection, and a willingness to make even the smallest of adjustments in order to reach new heights as players. This book is a very accurate portrayal of modern-day player development and the ongoing pursuit of individual greatness."Mike Hazen, Executive Vice President & General Manager, Arizona Diamondbacks

-

"A lot of books have claimed to be Moneyball 2.0, but this book actually delivers. It chronicles the changes that are transforming the game of baseball at a fundamental level and shifting power back into the hands of players and coaches."Mike Fast, Special Assistant to the General Manager, Atlanta Braves and former Director of Research and Development, Houston Astros

-

"Travis Sawchik and Ben Lindbergh are always at the forefront of the analytics revolution. The MVP Machine brings us the newly emerging competitive advantage whereby players are joining the intellectual advancement of the game and utilizing the new tools available to build a better Major League Player. Make no mistake, this is how games, divisions, and World Series titles are now being won."Brian Kenny, MLB Network