By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

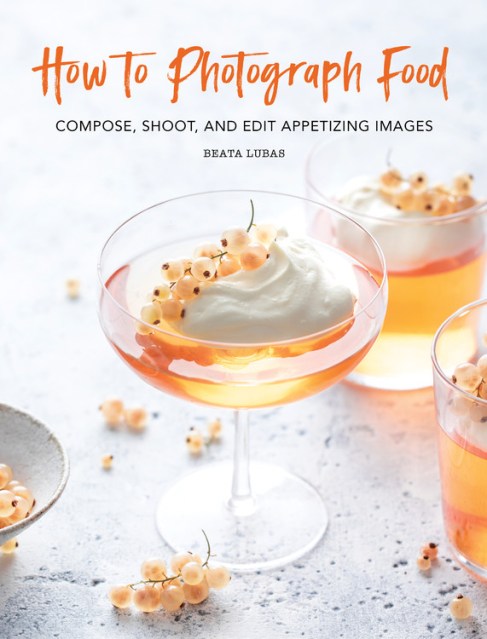

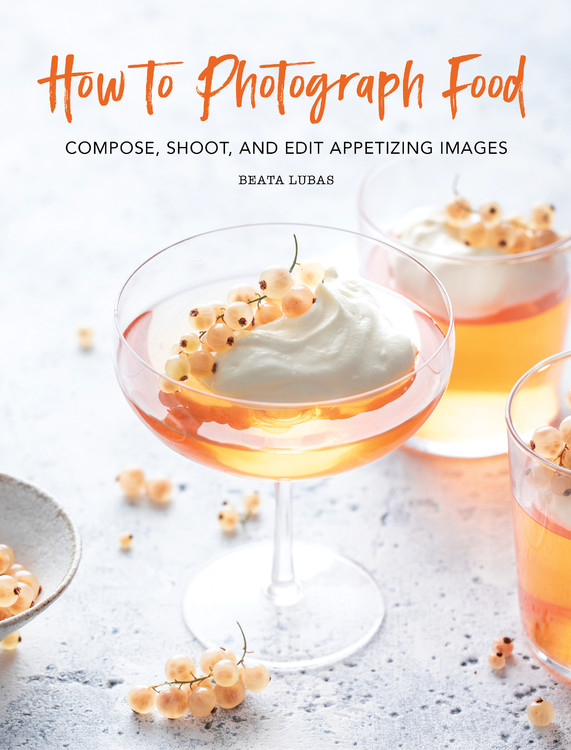

How to Photograph Food

Compose, Shoot, and Edit Appetizing Images

Contributors

By Beata Lubas

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 29, 2020

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762499625

Price

$25.00Price

$31.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.00 $31.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 29, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For amateurs and pros looking to add to their portfolios, How to Photograph Food makes food photography a piece of cake!

How to Photograph Food is the gorgeous, informative photography book you didn’t know you needed. For budding photographers and social media personalities, the perfect image has never been easier to capture, and How to Photograph Food puts it all within reach. Chapters include:

- Gear

- Lighting

- Frame and Balance

- Food Styling

- Photo Editing

- Thinking like a Pro

You’ll learn the essential equipment, how to keep food looking good on a shoot, how to work with props, managing lighting, and much more, all from a skilled photographer and teacher. With only a digital camera and a little practice, you’ll be able to turn out images with great contrast, balance, and appeal that look as good as they taste.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use